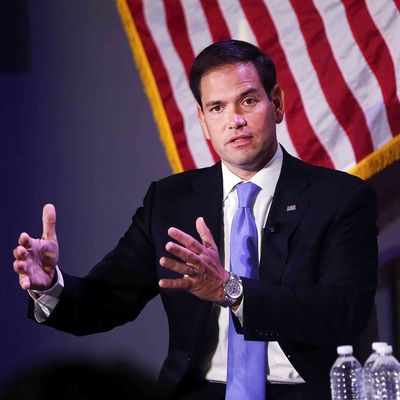

Many of us have noted that Marco Rubio has carried out an eerie reprise of George W. Bush’s 2000 strategy, which uses a combination of personal authenticity, small-bore policy concessions, and rhetorical misdirection to portray his conventionally Republican, supply-side policy agenda as a refreshingly moderate departure from party orthodoxy. The parallel can be seen, too, in the swooning coverage both figures have attracted from commentators who don’t worry too much about how it will all add up. David Brooks today supplies the kind of reaction Rubio’s campaign is counting on:

At this stage it’s probably not sensible to get too worked up about the details of any candidate’s plans. They are all wildly unaffordable. What matters is how a candidate signals priorities. Rubio talks specifically about targeting policies to boost middle- and lower-middle-class living standards.

Don’t focus on the substance of his policy commitments, argues Brooks. Focus on the rhetoric in his speeches. Because when politicians talk upliftingly about their hopes and dreams for hardworking Americans, that is when they reveal their most genuine selves. Pay no attention to the $6 trillion tax cut behind the curtain!

One defense of Rubio’s alleged moderation is that he would cut the top tax rate to 35 percent, as opposed to the even lower rates proposed by various other candidates and multilevel marketers posing as candidates in the GOP field. But, remember, the Bush tax cuts also cut the top tax rate to 35 percent. Bringing that rate back to that level was the subject of intense political struggle in 2001 and again in 2012 to 2013, because there is a lot of money at stake. And whereas Bush merely reduced taxes on dividends and capital gains — forms of income that overwhelmingly accrue to the very affluent — Rubio would eliminate them altogether.

Rubio does create a $2,500-per-child tax credit, which would help families if it was refundable. (Rubio’s campaign has said it would not be refundable, and thus do very little to help the poor.) Even if we assume otherwise, however, the assumption that Rubio’s tax cut helps the poor relies on the assumption that his proposals have no trade-off whatsoever. In reality, reducing federal revenues by $6 trillion over a decade would put immense pressure on the federal budget. Rubio has already promised to increase defense spending and keep Medicare and Social Security untouched for current or near-retirees, making them unavailable for budget savings within the next decade. Those programs — along with interest on the national debt, which cannot be cut — account for two thirds of the federal budget. Domestic discretionary programs, which fund things like transportation, scientific research, and the basic nuts and bolts of the federal agencies, have been cut so deeply that even many Republicans are eager to lift their caps. That means the brunt of Rubio’s fiscal pressure would come to bear on the minority of the federal budget that goes directly to the poor.

This is how Republican budget logic works in general. When you add up fanatical opposition to higher revenue, a political need to protect current retirees and a commitment to higher defense spending, you wind up either blowing up the budget deficit or inflicting massive harm on the poor. There are different ways to handle that problem. One of them is the Paul Ryan–circa-2011 plan of just proposing enormous cuts in anti-poverty programs. Another is the Paul Ryan–circa-2014-to-the-present plan of keeping those cuts in the budget but insisting they’re not your actual ideas.

Then you have the Rubio-Dubya method. The downside of this plan is that you don’t get Ryan-esque praise as a serious budget hawk who’s willing to look America square in the eyeball and tell us hard truths. But liberating yourself from any pretense to obeying the laws of arithmetic provides certain upsides that seem profitable for Rubio. You can give your party’s financial base the lucrative policy substance it craves, and craft your public message to the needs of the general election, by talking up your modest background. Bush in 2000 made a habit of taking photo opportunities with African-Americans all the time, a smart gambit that contributed to his image as a centrist. Rubio’s personal identity gives him a leg up in this regard. The only flaw in the plan is the possibility that reporters will focus on the substance of your agenda instead of the “signals” you send with your political messaging. If David Brooks is any indication, Rubio doesn’t have much to worry about.