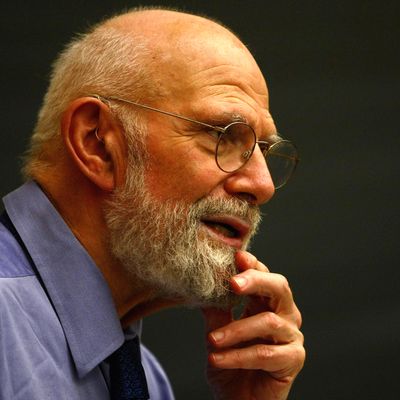

Oliver Sacks, the renowned neurologist, gifted author, and empathetic explainer of all things brain, died today at his home in New York City. He was 82. An author of more than a dozen books — millions of copies of which are in print — the medical doctor was among the most popular and widely read scientists in the world. In books like The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Awakenings (later adapted into a major film starring Robin Williams), Dr. Sacks used his patients’ disorders to elucidate the wonders of neuroscience, consciousness, and the human condition. Notes the New York Times in their obituary:

Dr. Sacks variously described his books and essays as case histories, pathographies, clinical tales or “neurological novels.” His subjects included Madeleine J., a blind woman who perceived her hands only as useless “lumps of dough”; Jimmie G., a submarine radio operator whose amnesia stranded him for more than three decades in 1945; and Dr. P. — the man who mistook his wife for a hat — whose brain lost the ability to decipher what his eyes were seeing.

Describing his patients’ struggles and sometimes uncanny gifts, Dr. Sacks helped introduce syndromes like Tourette’s or Asperger’s to a general audience. But he illuminated their characters as much as their conditions; he humanized and demystified them.

Said Nobel Prize–winning chemist Roald Hoffmann,“What others consider unmitigated tragedy or dysfunction, Sacks sees, and makes us see, as a human being coping with dignity with a biological problem.” As Sacks himself once told People, “I love to discover potential in people who aren’t thought to have any.”

Mind Hacks blogger Vaughan Bell, who is part of a generation of neuroscientists inspired to their field by Sacks, adds:

[He] wrote what he called ‘romantic science’. Not romantic in the sense of romantic love, but romantic in the sense of the romantic poets, who used narrative to describe the subtitles of human nature, often in contrast to the enlightenment values of quantification and rationalism.

In this light, romantic science would seem to be a contradiction, but Sacks used narrative and science not as opponents, but as complementary partners to illustrate new forms of human nature that many found hard to see: in people with brain injury, in alterations or differences in experience and behaviour, or in seemingly minor changes in perception that had striking implications.

Dr. Sacks was born in London in 1933 to physician parents who he said had a gift for medical storytelling. As a child, he was drawn to chemistry and its processes, and ultimately got a medical degree at Oxford. Sacks also grew up with a brother who was tormented by schizophrenia and the drugs used to treat it, which helped push the young Sacks toward science and medicine, and influenced his later work with patients. Dr. Sacks eventually moved to California in 1960, and later, permanently, to New York, where he practiced neurology for decades and explored the source material for his many books and essays on subjects like colorblindness, amnesia, phantom limbs, autism, hallucinations, music, and deafness — as well as his own memoirs, which he based on the nearly 1,000 personal journals he had kept throughout his life.

In February, Sacks announced that he was facing the late stages of terminal cancer via an ocular melanoma that had subsequently spread to his liver. Remarked Sacks in that announcement, “While I have enjoyed loving relationships and friendships and have no real enmities, I cannot say (nor would anyone who knows me say) that I am a man of mild dispositions. On the contrary, I am a man of vehement disposition, with violent enthusiasms, and extreme immoderation in all my passions.”

And, of course, he also used the opportunity to reflect on his own inevitable — but suddenly more immediate — demise, essentially eulogizing himself in advance:

When people die, they cannot be replaced. They leave holes that cannot be filled, for it is the fate — the genetic and neural fate — of every human being to be a unique individual, to find his own path, to live his own life, to die his own death.

I cannot pretend I am without fear. But my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written. I have had an intercourse with the world, the special intercourse of writers and readers.

Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.

Dr. Sacks, who never stopped working with patients and who published yet another new essay just a few weeks ago, is survived by his partner, the writer Bill Hayes, whom he had been with for the last eight years.