Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

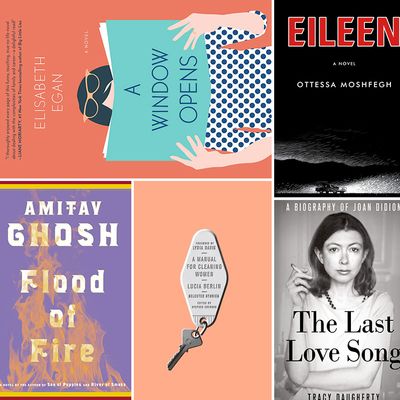

A Manual for Cleaning Women: Selected Stories, by Lucia Berlin (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, August 18)

May we never run out of great, unsung authors to unearth after they die, as Berlin did in 2004. Her 76 stories, more than half of them collected here, range widely in location and technique: a post-funeral Mexican vacation introduced via tourists’ chorus; an Oakland cleaner’s life meted out in bus routes; a woman remembering, in local twang, her journey across the El Paso border for an abortion. Together, they make up the mosaic of Berlin’s thinly fictionalized, widely traveled, and traumatically eventful life, a Knausgaardian journey by other means.

Street Poison: The Biography of Iceberg Slim, by Justin Gifford (Doubleday, August 4)

Before there was rap, there was pulp — mainly the work of Robert Beck, a.k.a. Iceberg Slim, the criminal who went on to write the best-selling memoir Pimp and several niche novels. It wasn’t just his stories that inspired gangsta rappers (including part-namesakes Ice Cube and Ice-T), but the story of his life. He transcended the victimizing ghetto first by victimizing others and then by mythologizing that feat in popular art. Gifford, an academic attuned to the vernacular, assesses that wild life story with clear eyes and an understanding of its true cultural scope.

Flood of Fire, by Amitav Ghosh (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, August 4)

If ever a historical book series deserved an HBO mini-series, it’s the one that concludes here, with the first Opium War and Britain’s 1841 seizure of Hong Kong. The Ibis trilogy’s first novel, 2008’s Sea of Poppies, opened in the fields of India, ended with a daring ocean escape, and came with a glossary of the nautical lingua franca of Asian colonialism. The polyglot story has since stretched and loosened, but Ghosh has stayed with the theme — the clash of personal desire and implacable commerce — without losing sight of the power of a kick-ass naval-battle sequence.

A Window Opens, by Elisabeth Egan (Simon & Schuster, August 25)

Diving headfirst into the territory where the having-it-all quandary meets the roman à clef, Egan draws on her suburban life, her job at Glamour, and her brief stint at Amazon (conspicuously left out of her author bio) for a funny and surprisingly wise piece of work. Favoring cleverness and precision over cartoon villainy and keeping her heart tucked under her sleeve, Egan makes a memorable heroine of Alice Pearse, who juggles family troubles and a new job at Scroll, a Starbucks-Amazon hybrid where acronyms reign and the bosses have either two faces or none.

Eileen, by Ottessa Moshfegh (Penguin Press, August 18)

Clumsy labels like “unreliable” or “unlikable” fail to capture the magnetic repulsiveness of this debut’s pitiable antiheroine and the 1960s Massachusetts town that confines her. Fifty years after the novel’s events, an utterly transformed Eileen remembers, in one chapter per day, the Christmas week during which her Northern Gothic existence — fetid house, drunken father, job at a boy’s prison — gave way to a strange crime and a final escape. Like The Woman Upstairs and Notes on a Scandal, Eileen turns on the symbiotic relationship between love and hate, hope and delusion, and — for the reader — repulsion and absolute absorption.

The Incarnations, by Susan Barker (Touchstone, August 18)

It’s 2008, and the Olympics are coming to Beijing, a city whose drab present state belies its too-interesting history, when a taxi driver with his own tortuous past finds himself stalked by a correspondent claiming to recount their six intertwined past lives. One thousand years of history, from cruel empires through Mongol raids on down to the Cultural Revolution, tumble through the stalker’s letters and propel Driver Wang toward madness (or does his madness invent them?) before a perfect conclusion brings home the writer’s warning: “History is coming for you.”

The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion, by Tracy Daugherty (St. Martin’s Press, August 25)

The past biographer of Donald Barthelme and Joseph Heller, Daugherty has the confidence to write an unauthorized book on a living person that trawls not just for gossip (though there’s plenty on Didion’s mostly-charmed life and its late unraveling) but for connection and, ultimately, meaning. It helps that his quarry traffics in exactly the kind of “limited narrative” Daugherty is forced to tell. Nonetheless, he gets friends talking, and he nails the ways in which history and culture shaped a writer who returned the favor — whose “style has become the music of our time.”