New Yorkers have heard a lot about how popular the year-old bike-share program is, and in some ways that’s true — locals have really taken to it, and the Citi Bank blue is ubiquitous in most of Manhattan and certain parts of Brooklyn. Among those meant to subsidize the system, though — tourists — it’s a different story. And for months, the weather has not been kind to the cause. The Wall Street Journal reports today that Citi Bike needs to — “quickly” — “raise tens of millions of dollars to rescue the popular bike-share program as it loses money.” New transportation commissioner Polly Trottenberg has acknowledged “a number of financial and operational challenges,” four of which we’ve laid out below.

The Winter

The decision by the Department of Transportation and NYC Bike Share to leave the system open year-round, unlike similar bike programs in cities like Boston and Montreal, left a lot of logistical questions. Many remain unanswered and the execution throughout the cold months wasn’t flawless: Riders complained as bikes went missing for maintenance or protection, leaving certain stations empty for days at a time.

More important, while average ridership was always going to go down, the especially brutal winter made for a huge drop, especially among riders with day passes. That, unfortunately, is where the money is, which brings us to …

Who’s Riding

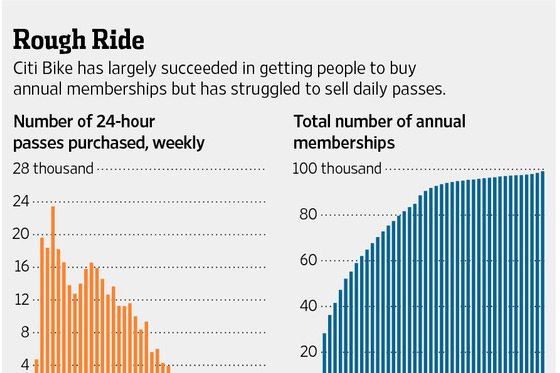

As the Journal reports, Citi Bike’s “managers don’t believe it can survive if it doesn’t become more appealing to tourists and expand to new neighborhoods.” Although 99,000 people have $95 annual memberships (mostly people in wealthier, whiter neighborhoods, unsurprisingly), revenue is more likely to come from the 24-hour ($9.95) and weekly ($25) passes.

Tourists have struggled with the glitchy payment system, sure, but the cold just stopped any momentum the program had as a fun activity in its tracks. Spring may have finally come, but then there’s next year to worry about. From November through March, as the Journal’s chart shows, day passes were just dead:

Raising prices is one consideration, although that’s unlikely to cover the huge gap in funds. (The program’s exact finances are kept private.)

Day-to-Day Operations

As mentioned early, the process of making sure stations are stocked, even after people use bikes for one-way trips, can be daunting. It requires manpower, which is expensive, and the Journal cites New York City traffic as an additional hurdle. A subcontractor to handle charging the docking station batteries every night is yet another cost. Plans to expand more stations to new neighborhoods also means more work, and the flow has not yet been perfected.

Branding and Sponsorships

Bike-share programs in most other major cities, including San Francisco, Boston, and Chicago, use public funds; New York City does not and doesn’t plan to — the lack of city subsidy was a Mayor Bloomberg selling point and the reason they’re called Citi Bike at all. However, the Journal reports, “Finding additional sponsors has proved challenging because the program has become so closely associated with its eponymous supporter.” Why would a company spend millions to align itself with something already burned into the public consciousness as belonging to Citi Bank?

The solution may be to seek out a benefactor in favor of the program but with nothing to sell. Now, where could the city find someone very generous, with billions of dollars and a stake in the bike share’s success? Maybe the guy who helped bring it here in the first place. We could get used to calling them Bloomberg Bikes.