There had been threats up in Binghamton, a near riot out on Long Island. Yet here in Crown Heights, when state education commissioner John King arrives for the latest stop on his “listening tour” about the implementation of new public-school standards, things are weirdly calm. Though the volume is distinctly lower, the stakes are not—and the dynamics far more intriguing than mere exchanges of shouts.

King is traveling the state to discuss the Common Core, a set of federally-supported math and English standards.* New York schools began teaching the new material last year; last spring’s scores on the first round of the much tougher Common Core tests were so low it appeared kids had stopped going to school entirely. Common Core has quickly become the new flash point in the public-school wars—teachers unions and opponents of increased standardized testing are fighting its rollout. For King’s visit to Brooklyn, though, the protesters were outflanked: Representatives of StudentsFirstNY, the local branch of Michelle Rhee’s big-money school-reform outfit, arrived early, distributing identically hand-painted signs and filling nearly the entire speakers list with pro-Core parents whose remarks hit the same talking points.

The emotions, though, are raw and movingly sincere. Ayana Bowen, one of the parents supporting the new criteria, starts speaking slowly, trying to hold it together, describing life in Brownsville. The city is phasing out the nearby failing elementary school; the replacement, P.S. 401, has gotten off to a rocky start—one second-grade class had five different teachers in six months. Ninety-five percent of the students qualify for free lunch; zero percent of the students are white. This, Bowen says, is where her 5-year-old daughter, Jayana, is in kindergarten. “It sickens me that people are against Common Core,” she says. Then her composure crumbles. Her eyes brim with tears. “Just because we reside in a lower-income community doesn’t mean my child should have lower potential. People in better-off communities like Park Slope or the Upper East Side want to lower standards for my child.” When she finishes, there is scattered applause, but mostly humbled silence.

A few minutes later, out in a hallway, Bowen has stopped quivering, but her desperation is just as palpable. “I went to public school in East Flatbush—it wasn’t great, but it wasn’t as bad as they are now,” she says. “The new mayor, what’s his name? He says he’s for higher standards for everybody. But I am not going to believe it until I see it.”

Bill de Blasio grabbed headlines and votes by emphasizing a handful of themes and policy ideas. One of his fundamental campaign pledges was that he’d “end the stop-and-frisk era” and mend relations between cops and minority communities. De Blasio’s first big decision as mayor-elect was to take a step in that direction—while at the same time reassuring the city’s elites that blood wasn’t going to start running in the streets—by reinstalling Bill Bratton as police commissioner. Keeping the city safe while minding civil liberties certainly won’t be easy. But reforming the NYPD is a box of chocolates compared with what awaits De Blasio’s schools chancellor, whomever he or she turns out to be.

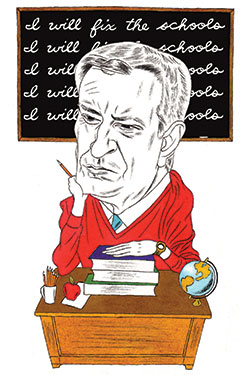

The mayor-elect’s other signature proposal as a candidate was a tax on the wealthy to pay for expansions of prekindergarten and after-school programs. Yet even if those changes were to take effect on January 2, they would be fairly minor parts of the byzantine schools puzzle, especially for the 1.1 million kids already in the system. There have been significant gains during the past twelve tumultuous years of Michael Bloomberg’s schools revamp—a willingness to try new pedagogical methods and school structures, an increased sense of urgency among principals and teachers—but the challenges remain thornier and the players more contentious than anywhere else in city government. Almost no one agrees on the solutions to the biggest problems: Graduation rates have improved dramatically, but 35 percent of the city’s public-school students still don’t get a diploma—and the majority of the students who do aren’t capable of handling college-level courses. Poverty and dysfunctional families are forcing schools to shoulder a greater share of parenting on top of teaching grammar and algebra. The vast majority of teachers are eager to use whatever tools work best—but retraining teachers isn’t as easy as redirecting cops because of everything from the paramilitary culture of the NYPD to the imprecise science of education.

De Blasio’s friendlier tone, and presumably that of his chancellor, gives him a head start, as does his (and his wife Chirlane McCray’s) experience as a public-school parent twice over. He’s going to need every possible edge to confront the serious problems that already exist or loom just over the horizon. Starting with Common Core. Teachers are learning the new English and math curricula at the same time they’re teaching them to kids, and the transition has been turbulent. Who deserves the blame is just one of many raging disputes between DOE and the teachers union. “However they feel about Common Core, they’re stuck with it,” says David Bloomfield, a Brooklyn College education professor. “The new administration has to figure out the professional development necessary to implement it better. That’s a major challenge.”

*This column has been corrected to show that Common Core is not federally mandated.

Then there’s the matter of failing schools. By the Bloomberg DOE’s count, 70 are in trouble, with a sizable fraction likely at risk of going out of business if the mayor were sticking around for a fourth term. De Blasio has promised a moratorium on school closures but hasn’t said much about how he’d improve the bad ones beyond providing them better “support.” Thirty-five new schools were approved to open in the fall of 2014. Some could be hopeful destinations for students whose old schools are struggling, even if they aren’t shut down under the new regime. De Blasio’s chancellor will need to determine fairly quickly if the plug is going to be pulled on the new schools that are ramping up.

Hovering over everything, though, is money. The teachers have been working without a new contract since 2009; the old one, according to the DOE, has provided annual raises of 3.6 percent on average in the years since, but United Federation of Teachers president Michael Mulgrew is looking for more and says he believes there’s $4 billion being paid to outside consultants that could instead go to his membership. Still, De Blasio has 151 other municipal unions he needs to negotiate with. And one crucial element of the UFT bargaining, at least when it comes to delivering higher-quality instruction to kids, may revolve not around dollars but work rules. You are to be forgiven if you thought Governor Cuomo had resolved the impasse over teacher evaluations—the law establishing evaluations did indeed get passed, but the union still has the right to haggle over the all-important details of how teachers are assessed. Mulgrew and one of his old adversaries from the DOE, former deputy chancellor Eric Nadelstern, use the same three words to describe the situation: “It’s a mess.” Perhaps it’s no wonder that one of De Blasio’s top choices to become chancellor, who is currently a professor at Stanford, isn’t packing up to leave Palo Alto.

The yelling started pretty quickly. The parents of P.S. 107 in Park Slope knew the school had problems: Enrollment was down as more affluent families, particularly white ones, sent their kids to the more prestigious P.S. 321. Now, on a spring night in 2000, the district superintendent was threatening to send in special-ed programs to fill the empty seats. Some parents loudly accused him of mounting a “witch hunt” against the principal; because Viola Harper was black, the argument took on a tense racial subtext.

Then from the back of the room came a calm voice: “Folks, guys, parents—this is a time for you to come together. This is a really important time. You will have more strength and more impact if you stay together and figure out how you want to move forward from here, rather than come apart and start fighting with each other.” The tall, goateed man was a school-board member who’d won his first run for office only months earlier. It was a very early demonstration of De Blasio’s ability to read the strategic realities—Harper was irreversibly on her way out—and of his gift for consensus-building. Like almost all stories about the schools, the ending isn’t tidily happy: Tempers flared more over the next few months, even as De Blasio helped guide the parents toward the choice of a talented new principal. P.S. 107 improved greatly, but gentrification has homogenized its student mix. The new mayor’s greatest mission is narrowing the gap between New York’s two cities, so that Brownsville doesn’t just get the same standards as Park Slope but the same quality of government services. Picking a tough and nimble chancellor will be crucial. Even more important will be whether Bill de Blasio can take the talents for peacemaking and political maneuvering he displayed in that one school in his own backyard and scale them across five boroughs’ worth.

E-mail: chris_smith@nymag.com.