I’m a pretty big fan of Monopoly. Not enough of a fan to attend gaming conventions, but if people are playing board games, that’s the game I nominate. Nearly every time I suggest it, people say the same things: It takes too long. The game is all luck. They believe these things because they don’t know how to play the game. Ignorance of Monopoly is so widespread that Slate recently produced an explainer of how to win at Monopoly using economic theory. The guys who made it clearly don’t know how to play the game, either. If you think the game is all luck and takes forever, you’re playing it wrong. Here’s how to play it right.

Don’t create a cash bonus for landing on Free Parking. This convention has spread through the culture out of ignorance, although the official rules don’t allow for it. But more importantly, a Free Parking bonus increases randomness and makes the game take much longer. That’s because in Monopoly, the balance between cash and property is crucial. There is a fixed amount of property. Every player starts with a set amount of cash, and the total amount of currency stays relatively level as players bring money into the game by passing Go, or take it out by purchasing property, houses, or hotels. A Free Parking bonus creates a large in-game lottery and floods the market with extra money, making it much harder to force players into bankruptcy. Even worse, it creates inflation – money that is supposed to go out of circulation instead stays in the game and is handed out to random players. As a result, there is more money chasing the same amount of property, making property more valuable than its listed price. That is one reason why many people think the obvious strategy is to automatically buy up every property you land on.

Trading is the key to the game. The subtleties of the odds concern which properties to develop, and at what level. The un-subtle thing is that having monopolies of any kind are vastly better than not having a monopoly. If you’re extremely lucky, you can get a monopoly by landing on all three properties in a group when they’re unowned, and buying them up. That almost never happens. To get a monopoly, you almost always have to trade. The strategy of the game comes mostly from making creative trades.

Don’t play with just two people. Since Monopoly is mostly a trading game, two-person Monopoly is as useless as playing a game of open-hand poker. In a two-person Monopoly game — like in Slate’s explainer, or in Molly Young’s recent game of Monopoly with John Oliver — trading is pointless, because there’s no reason to make a trade in a two-person zero-sum contest. You need at least three people, and ideally, four to eight. (Also, the more players in the game, the more valuable property becomes relative to cash — a property you might pass up in a four-person game is one you’d buy in an eight-person game.)

Monopoly is a trading game. If you play with more than two people, then the possibilities for useful trading are immense. If I hold two yellows and one red, and you hold two reds and one yellow, our holdings are nearly worthless. If we make a deal such that one of us has all the reds and the other has all the yellows, then we have massively enriched ourselves.

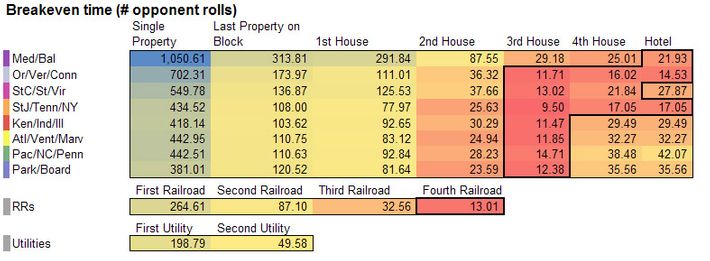

Some streets have far more value than others. The rate of return on your investment varies substantially between different property groups. Here’s a chart showing how many rolls it takes to recoup the investment on any given property:

Like poker, players who have at least a general understanding of the odds can crush players who don’t. Railroads are a good investment if you can obtain at least three. Utilities are nearly worthless. The Baltic-Mediterranean cheapo color group is also nearly worthless.

Don’t automatically buy up every property you land on. This is another common mistake by people who think Monopoly strategy is either simple or nonexistent. Property is valuable, but so is money. You can’t make any real money without investing in houses, and you can’t build houses without cash. Having a monopoly of one color, which allows you to build, is always better than not having a monopoly. Relatedly …

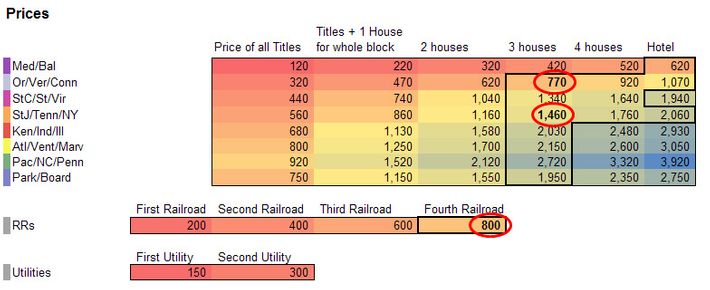

You need cash. The purpose of your trading strategy is obviously to gain a high rate of return investment. Therefore, your trading strategy has to account not only for the need to build a monopoly, but also for having enough cash to develop it. You can gain a high rate of return from building multiple houses on expensive properties, but it takes a lot of cash. Here’s is a second chart, from the same source, which has circled the three highest rates of investment. This chart shows how much cash is needed to buy the properties and develop them:

Look at, say, the dark green color group — Pacific, North Carolina, Pennsylvania. If you build three houses on each property, you can get a good-but-not-great rate of return, paying back the investment after 14.71 opponent rolls. But you need $2,720 to buy those properties and the houses. Since players only start with $1,600, your chances of building that into your first major investment are nearly zero. Even if you spent all your money buying (or trading for) the three greens and building on them, you’d need to get around the board six times to have the money to build. By the time you manage that, other players, if they’re any good, will have developed their own monopolies, and will be bleeding you for rent.

Move fast. The monopolies you have a chance to develop early in the game are the light-blue color group — Oriental, Vermont, Connecticut — and the orange group — St. James, Tennessee, New York. Those groups require, respectively, $770 and $1,460 to develop into a high-yield investment. The best strategy is to acquire one of those groups and the requisite cash. The profits can be used to purchase a second, more expensive monopoly if needed. But they’re profitable enough on their own that they can win you the game, especially if you develop them before any other players develop a high-yield monopoly. And remember, once you start collecting large rents, you take from your opponents the cash they need to develop their own monopoly, sucking them into a death spiral. A player who acquires a high-yield monopoly substantially earlier than the others is nearly certain to win.

Trade isolated properties. You don’t want to tie your money up in property that can’t be developed into a high-yield monopoly. If you start amassing extra cash reserves, use them to buy a second monopoly.

Don’t drive a hard bargain. Lots of people do this. It is a mistake. Trading is so positive-sum, it’s worth letting your partner get a slightly better deal. Quantity beats quality. Even if you have terrible luck in buying up properties, you should still be able to trade your way to a monopoly by making cash deals — after all, a player who acquires a monopoly can’t do anything with it unless he has money to buy some houses.

Don’t wait to trade. Some players like to wait until all the properties have been bought up before making a trade. That’s a completely arbitrary principle that only hurts them. There’s no reason not to make a trade that gets both parties closer to the position of having the property and money needed to make a profitable investment.

When you have a monopoly, build three houses on each property. Once you have a monopoly, your priority should be to obtain enough cash to buy three houses on each property. Three houses is the point where the rate of return takes a huge leap — investments below that level take far too long to pay themselves back. Adding a fourth house or a hotel is fine if you have extra cash to invest, but that cash is better spent developing a second or third monopoly, if you can acquire one.

There is (almost) no luck. Luck matters in Monopoly only if all the players understand the fundamentals of the game’s strategy and understand the varying rate of return of different investments. I’ve never played a game of Monopoly where that’s the case. Players who understand the odds and strategy of the game should virtually never lose to ones who don’t.