My father’s kidnapper seemed like a decent man when we first met.

At the time, I didn’t know who he was, and he wasn’t aware of my family’s history. Entirely by chance, I was interviewing him for a story I was reporting in Lebanon, where I’m partly based. I can’t reveal much about him, but I will say that he is now a Hezbollah official in the south of the country, close to the Israeli border.

It was a good interview. The official gave me some fantastic quotes, and I could tell we had established a rapport by the end, which meant I could use him as a source in the future. When the interview was over, my translator happened to mention, almost offhand, who my father is.

The man went completely white. The blood actually drained from his face. “I feel ashamed,” he said. “You must hate us.” And for the most part, I did.

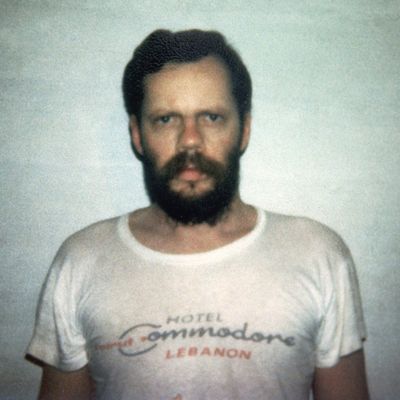

In March 1985, three months before I was born, my father, Terry Anderson, was kidnapped by Shiite Muslim militants calling themselves the Islamic Jihad Organization. It was a group that would come to be associated with Hezbollah, the powerful Iran-backed militia and political party. After almost seven years of confinement and torture, Dad was released, and I met him for the first time. (All of this is described in my new book, The Hostage’s Daughter, as are my conversations with my father’s kidnapper.)

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a terrorist as “a person who uses unlawful violence and intimidation, especially against civilians, in the pursuit of political aims.” As a reporter working in the Middle East, I’ve interviewed many people who fit that description, from imprisoned ISIS members to Hezbollah fighters to Islamist militia leaders. My conversations with them, as well as my interactions with the man who kidnapped my father (which took place over the course of a year), have given me a very particular lens through which to view one of the great questions of the 2016 United States presidential election: how to “make America safe again,” to borrow a phrase Donald Trump used in a debate this month.

To me, one of the keys to answering this question is understanding the phenomenon of terrorism at a deeper level, so that we can do everything in our power to prevent those situations from taking place again. When I asked the man in South Lebanon why they chose my dad in particular, his answer forever shaped my understanding of how someone justifies terrorism.

“When we took your father, we didn’t see him as Terry Anderson, the person,” my father’s kidnapper told me. “To us, he was America.”

It has since become clear that this man and his friends were responsible for the dawn of a new era that eventually came to include 9/11, Orlando, and dozens of other terror attacks. My father’s kidnapping and the events surrounding it were one of the first incarnations of Islamic terrorism against the United States. The Islamic Jihad Organization, the group that held him hostage, also introduced suicide bombings as a terror tactic against Americans — one that has evolved into the stuff of our nightmares.

At the time U.S. installations in Lebanon were being bombed, the United States was arming and sponsoring Israel, which invaded Lebanon in 1982 to drive out the Palestinian Liberation Organization. In fairness, the PLO was at war with Israel at the time, Lebanon’s 15-year civil war was in full swing, and the Lebanese were already doing an impressive job of killing each other. But even after the PLO fled Lebanon, the Israeli occupation continued, and it was a long, brutal process that led the majority of Lebanese Muslims to view the United States as an aggressor in the conflict on Israel’s side. The Israeli army would continue to occupy South Lebanon for another 18 years, not withdrawing until 2000.

As one former high-ranking State Department counterterrorism official told me while I was reporting the book: “There is a high correlation between being occupied and terrorism … in the case of Lebanon, there was the Israeli invasion. That tends to make someone far more militant and desperate … and what you will sometimes do if you can’t actually get at your immediate occupier is to go for their outside supporter.”

My father, who was bureau chief of the Associated Press at the time he was taken, was not the first American to be kidnapped, but he was held the longest. The man I met in South Lebanon and his friends showed my dad little mercy while he was under their care. He was confined in inhumane conditions and subjected to regular beatings and psychological torture for almost seven years.

During our interviews, my dad’s captor, who was 17 years old at the time he began guarding my chained, blindfolded father, told me that he participated in the kidnappings because he was consumed by helplessness as he watched his country be occupied with U.S. support. His leaders recruited him because they saw a chance to exploit his anti-Americanism for their own ends. To be very clear, I am not justifying what my father’s kidnapper did. I listened to him because I wanted to understand it better, in part so I could learn about how to prevent others from taking up his cause.

Thirty years after my father was kidnapped, if we want to do everything we can to prevent attacks against Americans, we should probably start by listening to ISIS. In August 2013, I interviewed a Salafist sheikh named Omar Bakri. Famous in the United Kingdom for his radical rhetoric — including praising the September 11 hijackers — the cleric was exiled to Lebanon in 2005. Since I last spoke with him, Bakri was arrested and sentenced to 12 years of hard labor in a Lebanese prison for terrorism-related offenses. His name also surfaced earlier this year in leaked ISIS documents that reveal him to have worked as a recruiter for the terrorist group.

When I met him, he was denying all material ties to Al Qaeda and ISIS — though he openly embraced their ideology. At some point during a two-hour rant about the merits of “true” Islam (or his extremist version of it) and the evils of the West, he said something very significant.

“The West and true Islam cannot exist at the same time,” he told me. “They are existential enemies, and we welcome the final battle between them.”

This idea that America and Islam are inherently incompatible and must fight to the death should sound familiar. It is the same rhetoric employed by elements of the American far right and embraced by Donald Trump. Since the beginning of his campaign, the Republican nominee has unceasingly lambasted the Obama administration’s supposed lack of progress in the military and existential war on terror, even warning that if Clinton is elected, ISIS will “take over” the U.S. Of course, he also finds Islam and America incompatible enough that he pledged late last year to institute a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.”

ISIS seems to be a fan of Trump’s rhetorical style. In fact, there is evidence that strongly indicates the single most brutal and successful radical Islamist terrorist group in history is actually rooting for a particular candidate in this American election. Interviews with ISIS members as well as analysis of ISIS-affiliated social media have shown that the group is doing everything it can to facilitate a Trump win. He has even been featured in propaganda videos for ISIS and other Al Qaeda–affiliated groups.

“We were happy when Trump said bad things about Muslims because he makes it very clear that there are two teams in this battle: the Islamic team and the anti-Islamic team,” one ISIS defector is quoted as saying in Foreign Affairs. He is “the perfect enemy,” another explained.

This situation is unprecedented, and deserves intense consideration by the American public. A man as close as one can possibly be to becoming the elected leader of our country is being cheered on by people who want to obliterate our way of life.

But if the final battle between Islam and the West is what’s playing out in Iraq right now — as a U.S.-led coalition of local military actors including the Kurdish Peshmerga and Iraqi army moves to retake Mosul, ISIS’s final stronghold in Iraq — then, overall, I’d say it’s not going so terribly for the West.

During the third presidential debate last Wednesday night, Trump doubled down on his criticism of Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s role in the U.S. military and counterterrorism effort against ISIS:

But who’s going to get Mosul, really? We’ll take Mosul eventually. But the way — if you look at what’s happening, much tougher than they thought. Much, much tougher. Much more dangerous. Going to be more deaths that they thought. But the leaders that we wanted to get are all gone because they’re smart.

The fact is, the current military effort against ISIS in Iraq has been making slow but tangible progress. Over the past few years, the Obama administration has adopted a policy of providing air support as well as training and military aid to local forces such as the Iraqi army and Peshmerga, instead of mounting a full-scale invasion using U.S. troops. Simultaneously, Russia and the Syrian regime have led their own joint effort against ISIS (as well as other rebel Syrian groups, such as those trapped in the besieged city of Aleppo). This approach seems to have enjoyed a certain measure of success, since ISIS lost much of its fighting forces as well as almost a quarter of its territory in just the last 18 months. And though it is still sure to be a long, hard fight against a well-armed, deeply entrenched, and increasingly desperate enemy, the battle for Mosul actually appears to be progressing cautiously well at this stage.

“We’ve seen on-the-ground progress in Iraq during the last six months or so,” Larry Goodson, national security expert and professor of Middle Eastern studies at the U.S. Army War College, told me recently during an interview. “I think it’s the best strategy, although not a very sexy strategy, so not one that demands headlines.”

My friend, the aid worker Peter Kassig, was kidnapped by ISIS and held for a year before being beheaded in November 2014. As with most of the Westerners ISIS executed, they recorded him before and after his death, which took place in a Syrian city called Dabiq. Dabiq is a place that has adopted apocalyptic significance in ISIS theology. Revered by the terrorist group as the future site of that epic final battle between “true” Islam and invading Western hordes, the city’s name shows up all over ISIS propaganda and social media. And yet, just over a week ago, ISIS fighters fled Dabiq, leaving it to an approaching force of Turkish-backed Syrian rebels — and rendering a crippling blow to the group’s intentions of sparking a massive conflict between Islam and the West. I cannot overstate the significance of that loss to the ambitions of ISIS — or, as someone who cares about Pete, to myself.

These victories seem to be good news for everyone, except ISIS … and Donald Trump.