The first thing you notice when you talk to Desh Amila, beyond the fact that he’s an outgoing and friendly guy, is that he has a lot of faith in the power of public debate to help improve the world. This stems in part from his background: The Australian entrepreneur and event organizer was born in Sri Lanka in 1981, not long before a civil war broke out that, over the course of 26 years, would kill as many as 100,000 people.

After emigrating to Melbourne in 2000, he created a chapter of Sri Lanka Unites, an organization built around the sad fact that, as its website notes, “We grew up in a society where ethno-religious identities were emphasized over an inclusive, equal Sri Lankan identity, and as a nation, Sri Lanka has been trapped in a vicious cycle of violence.” He did some reconciliation work back home and learned that “70 percent of my countrymen have not had a meaningful conversation with, or did not have a friend from, the other side.” He believes the civil war was, in part, “a failure of conversation.”

Desh (the surname he goes by; his full name is Amila Deshantha) has built a career out of facilitating intellectually oriented public events, often between people with serious disagreements. He co-directed Islam and the Future of Tolerance, a documentary centered on a debate between Sam Harris and Maajid Nawaz, a former Islamic extremist turned liberal reformer. The film originated from a tour of Australia that Desh put on with Harris, featuring Nawaz as a “special guest.” First as the head of Think, Inc., a company he has since sold, and now with the group This Is 42, Desh has organized events featuring top public intellectuals in Australia and elsewhere.

Given his previous work covering subjects like Islamic extremism and atheism, Desh probably didn’t anticipate that a conversation between two American feminists, both frequent contributors to mainstream publications, would spark one of his career’s messiest episodes, complete with legal threats and prolonged negotiations over whether the event’s video footage would be released. But that’s what happened. And it’s a rather telling, colorful story of what happens when the highest ideals of civil conversation collide with the realities of public-intellectual stardom and a thoroughly tribalized social media ecosystem. The saga shows that working through disagreement in this political era can be a bit more complicated and fraught than merely getting two disagreers onstage together.

It all started about a year ago, Desh says, when he was involved in a casual group conversation in which “a lot of people got really touchy the moment I mentioned I’m a feminist — I didn’t realize the actual term had morphed into something some people use as an insult.” This made him realize that “feminism definitely has a branding issue and people don’t seem to really understand what it is.” Two of his favorite feminists were Roxane Gay and Christina Hoff Sommers, and he wondered if it might be worthwhile to get the two onstage together in Australia. Gay, who has a Ph.D. in rhetoric, is the superstar author of books like Bad Feminist and Hunger and is an outspoken progressive on issues of gender and race. Sommers is a center-rightish “classical liberal” type with a Ph.D. of her own in philosophy and is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Though she has been an author and a public commentator for decades, Sommers is best known among younger audiences for “The Factual Feminist,” her YouTube video series, which leans heavily on “modern feminism has gone too far”–style arguments, racks up hundreds of thousands of views per video, and has spurred frequent criticism from left-of-center voices that she is less a genuine feminist than a conservative concern troll.

Desh reached out to them both. Sommers was excited by the idea but didn’t think Gay would agree; Gay’s management team was receptive but similarly skeptical. In June of last year, Desh says, he sent Gay an email laying out his vision and citing the famous Buckley-Vidal debate, itself the subject of a documentary, as his inspiration. “This is how conversation used to be,” he explained. Eventually, Gay agreed.

The original plan was to hold events in Melbourne, Sydney, and Auckland, New Zealand, but instead ended up as two conversations: in Sydney on March 29 and in Melbourne on March 31, the Auckland event being canceled due to lack of interest. The mini-tour was dubbed #Feminist.

***

Desh had put on all sorts of events about controversial subjects before and never had much trouble finding a host. This time was different. Desh says he reached out to about ten qualified potential hosts, seven of them female, and they all turned him down (he shared some of the emails with me, names redacted). Most didn’t explain why, but Desh says one told him that she “strongly disagrees with Christina Hoff Sommers and feels it would be hypocritical for her to share a stage with Christina.” (In a follow-up email, I asked him why, given how much lead time he had before the event, he’d asked only ten people to host. He said that he’s sought hosts to previous events about six weeks ahead of time, and figured that timeline would work here.)

This event became the subject of controversy a full six months ahead of its scheduled dates, when, in a September 2018 interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Gay called Sommers a “white supremacist,” a claim for which there doesn’t appear to be any evidence (Sommers is Jewish and says she is a registered Democrat, for what it’s worth). “Personally, I was a bit surprised that she used those words because if you look into Christina’s work, it’s far from that,” says Desh. “I was taken aback by that statement.” Gay had been asked about her decision to share a stage with a “white supremacist,” given that she had pulled a New Yorker article in response to that magazine having invited Steve Bannon to a New Yorker Festival (after the outcry, he was disinvited) and had also pulled a book she’d been contracted to write for Simon & Schuster after the publisher inked Milo Yiannopoulos to a (since canceled) deal. In response, Gay told the Morning Herald that she’d never heard of Sommers before but that after she’d mentioned the mini-tour on Twitter, the Southern Poverty Law Center, an anti-hate group, sent her information about Sommers that she found “disturbing.” (The SPLC has accused Sommers of making arguments that “overlap” with those of hard-line “male supremacist” groups, but the overlapping in question appears not to be about any radical male-supremacist claims but rather on issues where there is mainstream expert disagreement, such as the prevalence of sexual assault on college campuses and the magnitude and origins of the gender wage gap.)

Desh had been hoping for the events to be seen less as a “debate” — a term he says he explicitly avoided in the publicity materials — and more as a “conversation.” This was quickly proving to be naïve. The subject going in was not the nitty-gritty of the gender wage gap or the best ways to prevent sexual assault but the accusation that one of the participants was a white supremacist, along with the inevitable online sniping that occurred in its wake. A week or so before the event, still without a host, Desh decided the best route would be to host it himself — something he’d never done before. He knew the optics weren’t ideal for an event labeled #Feminist, but he didn’t see any other options.

Desh shared the audio of both events with me, and it’s clear from the start of the Sydney conversation that he’d attempted to leaven the situation with humor, as in this opening line: “I know what you’re thinking, What is this penis doing onstage?” That one got some laughter. He then explained the trouble he’d been having. “For some reason, no self-proclaimed feminist wanted to host this event — actually, nobody wanted to host this event. So as an immigrant, I’m doing the job nobody else wants to do.” More laughter with applause and cheers.

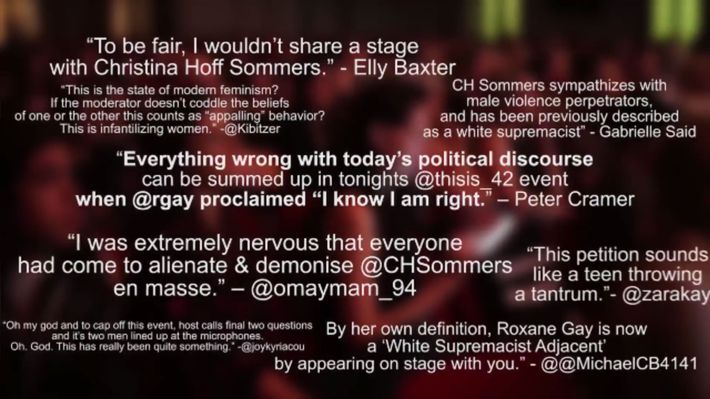

But from there things quickly devolved, and in Desh’s telling, the crowd was largely responsible. “Imagine a terrible, terrible YouTube comments section — but live,” he says. “People had already picked their sides when they came into it, we could hardly get words in, and people were chanting and yelling and screaming.” Omayma Mohamed, an Australian-Egyptian ex-Muslim in attendance whose tweetstorm about the event helped frame its subsequent online narrative (more on that soon), independently provided a similar accounting. “It felt like a sporting home game,” she told me in an email, “where the overwhelming majority of the crowd is there to see their player demolish their opponent, the outsider that they have no loyalty to. There was so much hostility in the room, with the spectators desperate to see Gay outdo Sommers at every turn. Each of Gay’s points was followed by loud applause, while Sommers was met with snickering and laughter even as she was speaking … I found it really difficult to concentrate on what was being said at times because the crowd was so disruptive, and it seemed like I was one of few who actually wanted to hear the exchanges in full.” In an email, Sommers said, “The audience was filled with noisy fans of Roxane — so I was a bit flustered at times. They tended to cheer at whatever she said and jeer at my remarks. But I have had that happen at schools like Oberlin and Lewis & Clark Law School. I’m always hopeful that I will get through to some audience members — even hostile ones.”

The audio generally supports these accounts. It’s clear the crowd was solidly pro-Gay and anti-Sommers and fairly rowdy, increasingly so as the event went on. At the same time, much of the conversation itself comes across as a fairly standard left-versus-right debate: occasionally interesting dialogue interspersed with a healthy dose of talking-point recitations. Here and there are moments when Sommers and Gay appear to agree, even if they don’t say so. When Sommers criticized the commonly repeated statistic that “one in five” women are sexually assaulted on college campuses, for example, Gay noted that it included sexual harassment, not just assault — meaning they agreed that the figure is an overestimate when it comes to assault. Both also seemed to agree that certain gray-area cases of sexual misbehavior, like that of Aziz Ansari, were not a good direction for the #MeToo movement (on Twitter, Gay had bemoaned the lumping in of the Babe.net bad-date story with more serious incidents like those surrounding Matt Lauer and Louis C.K.).

Afterward there was no question the event had been heated and the atmosphere a bit unruly, but opinion differed about its overall quality. “I thought Desh was a fine moderator,” said Sommers. “He asked fair and reasonable questions, and the event seemed to go okay.” At least some attendees appeared to agree: “I had a lot of people approaching me saying that they appreciated what I did,” says Desh. “Some people were joking, saying, ‘I’m glad I wasn’t onstage.’ And some people were saying, ‘I can see why nobody wanted to take on this job.’” Most people who approached him were positive about what they’d just experienced, though he acknowledged that was likely a biased sample. Twitter, meanwhile, was in an uproar, so Desh removed the app from his phone and headed backstage to ask the participants how they thought it went. Sommers gave a positive assessment; then Desh approached Gay and asked her the same question. It was “a shitshow,” she told him.

***

In the immediate wake of the Sydney event, some online misinformation about it began to spread, likely exacerbating the sense that some genuinely crazy or embarrassing stuff had gone down. Some Australian media accounts clouded the situation further. Rumors began to circulate that Desh had been unprepared for the event and had asked laughably basic questions. As Mary Ward of the Sydney Morning Herald, which is one of Australia’s most important newspapers, reported about one spectator’s reaction, “[She] said simplistic and overly broad questions (like ‘What is feminism?’ and ‘What is intersectionality?’) made the debate feel ‘cheapened.’” Gay pressed the same point in an email to me: “At the first event, he asked, ‘What is feminism?’ and ‘What is intersectionality?’ These were … terrible questions to ask an audience that had paid up to AU$247 to attend a feminist exchange of ideas.” (The cost of the event had been a point of contention between Desh and Gay and her management team. Desh says that prices were higher than usual because of Gay’s large fee and that AU$247 represented the highest tier of ticket, which included the best seats, food, and drink, plus a meet-and-greet. He says the standard ticket prices ranged from AU$42 to AU$67.)

Desh did ask Gay and Sommers to explain what intersectionality meant to them in a fairly 101-level way, but the sillier-sounding question he was accused of asking — What is feminism? — is a misrepresentation that makes it sound as if he’d wandered onstage, sweaty and shuffling papers, and sputtered, “So, like, what is feminism?” That wasn’t what happened. Rather, in opening the conversation immediately after the participants were introduced, he told a version of the story he’d told me about describing himself as a feminist (which got a strangely cool response from the audience) and, pointing out the surfeit of polling data showing that feminist is an unpopular label among young people, asked each guest for her own definition of the term. It comes across, in context, as an obvious means of cuing up some of the broader disagreements between Gay and Sommers. “His question on feminism was on point,” said Sommers. “Most Australians and Americans believe in gender equality yet don’t identify as feminist.” She also critiqued the media coverage: “The stories in the Australian press seem to have been written by reporters who did not attend the event. No one ever contacted me for comment.”

A slight but important misrepresentation of one of Gay’s answers spread on social media as well. It had to do with a question Desh asked about the proper role of Western feminists in the fight against oppressive gender mores and laws in places where harsh interpretations of Islam reign. To drive the question home, Desh played a video clip from a documentary of “Sharia police” in Indonesia harassing young women over their attire. In a tweetstorm (archived here), the first tweet of which got 2,700 retweets, Omayma Mohamed wrote that Gay said “it would be rich for a westerner to assume that they knew what was best for other cultures & that we didn’t need to intervene in their affairs. She said that we should wait for representatives of that culture to speak up, b/c after all, the west is also guilty of misogyny.” There’s some truth to the idea that Gay downplayed the differences between the women’s-rights fights in the West and in places like Indonesia (“We are dealing with the very same issues in the Western world when it is not encoded by Sharia law,” Gay said). But arguably the most inflammatory claim — that she said, “We should wait for representatives of that culture to speak up” — just isn’t true.

Here’s an excerpt from Gay’s response:

I also think it would be really presumptuous of me as a feminist to know what’s best for Saudi Arabian women, who have been very effective at organizing — we saw this especially in recent years as they fought for the right to drive. And from a Western perspective, you think, My goodness, you’re still fighting for the right to do this very basic thing and to have this very basic amount of independence? But I don’t know that they need external intervention. What they need is our support materially, probably financially, and certainly in terms of highlighting voices in those communities who are leading these movements to create change. So I think support can come in a lot of different ways, but I don’t think it needs to come in an interventionist way, because I don’t think we know better than what those communities need for themselves.

It’s clear Gay’s gripe was not with the idea of American feminists helping foreign feminists win their own fights but rather with doing so in an “interventionist” way (though the term is never defined in this part of the conversation). Sommers replied by more or less agreeing. So this was another area where, if you dug down a bit, there wasn’t a great deal of conflict between the two — not that it stopped Gay’s critics from spreading exaggerated accounts of her response on social media.

***

The true shitshow hit the day after the Sydney event. “I woke up to a number of emails from Roxane’s management, very, very upset at me,” says Desh. Seven of them, to be exact, with the first laying out the complaints of Gay’s team at the Iowa-based Tuesday Agency:

I have to let you know that Roxane wasn’t very pleased with the event last night.

I would ask you as a matter of courtesy to refrain from asking her personal opinions about CHS [Sommers] while onstage. Inciting a confrontation like that is poor taste, frankly. She’s a human being with feelings and so is CHS.

Also, showing the video regarding Sharia law took her aback as well. Please consider removing that segment from the Melbourne event.

The “personal opinions about CHS” refers to when Desh asked Gay onstage whether she actually believed Sommers was a white supremacist. In response, Gay hedged a little but never fully retracted the accusation, referring to Sommers as “white-supremacist adjacent” for having appeared onstage with Yiannopoulos, among other appearances — an apparent reference to a 2015 incident in which Sommers accepted an interview on a Swedish podcast that turned out to have a history of Holocaust denialism. (She acknowledged this on Twitter in March 2018, saying she had simply been unaware of the show’s history and posting a screenshot of an email she’d sent in early 2016 asking for the interview to be taken down.) Desh was being asked not to press Gay on the rather damning claim about Sommers that she had made without evidence, as well as not to bring up the topic of women’s treatment in countries with strict interpretations of Islamic law, which was salient to the differences in opinion between Gay and Sommers (not to mention a source of schism in the feminist movement itself).

Later that day, Gay’s management team unilaterally settled on a solution: Desh wouldn’t host the second conversation in Melbourne, at that point just a day away. Instead, they suggested Rachael Hocking, a journalist of indigenous ancestry at Australia’s NITV who had just interviewed Gay a few days earlier — in fact, Gay’s team had already reached out to her. “Here’s her number — contact her now,” Desh sums up the email he received. He says he can’t share the details of the event contract due to a confidentiality clause, but it was clear that Gay’s team had no right to choose the host. “It was always going to be our call,” he says, adding that the Tuesday Agency had been generally professional and was in his view simply trying to protect its client but that in this case their demands “were absolutely unreasonable.” They seemed to be attempting to install a pro-Gay host for the second event. Moreover, while Hocking told Desh she would do it, she was honest with him about having never heard of Sommers until Gay’s team had reached out, making her (in Desh’s view) a less than ideal choice.

So Desh contacted another possibile host: Meredith Doig, a feminist with a Ph.D. who is president of the Rationalist Society of Australia, a Medal of Australia winner, and one of Desh’s mentors. Doig said she’d do it if she had to, contingent upon the speakers’ agreement, but didn’t really have enough time to prepare, and she thought the request to unseat Desh as moderator was unfair. All day on the 30th and 31st, as Desh helped his small team pack up cameras, props, and other gear for the flight to Melbourne, emails from Gay’s team kept pinging his inbox. While at the airport waiting to fly to Melbourne for the event that day, he received several from Kevin Mills, a vice-president of the Tuesday Agency and the point person for the mini-tour. “I strongly urge you to go with Rachael,” read one. “Roxane will not put up with any more stunts provoking a reaction out of her or the audience.” Gay’s team made it clear that Doig was not acceptable. “We are not playing games, my friend,” read another. “Who are you planning on having for a moderator? Easy question.” Sommers, meanwhile, said she was fine with Doig but didn’t like the idea of Hocking hosting — she thought it was unfair for Gay to get to choose the host — and she preferred Desh overall.

Adding to the tensions, the day after the Sydney event Desh also received a legal threat from an Iowa-based firm representing Gay, demanding that he not release the video of the previous evening’s conversation and not record the following evening’s, on the grounds that “at no time has the Client or the Agency, as the Client’s designated representative, granted permission to You to record and/or publish the Performance.” As everyone involved now acknowledges, the letter’s claims were false. The Tuesday Agency did, in fact, sign a contract on Gay’s behalf granting full video rights to This Is 42 — Gay just didn’t realize the contract included full video rights. “I did not sign any contract with Desh. Kevin and Trinity [Ray, president of the Tuesday Agency] did,” said Gay in an email sent on April 19. “This was a huge mistake and one I only learned about yesterday. I have no idea what the contract says, and it’s deeply frustrating that this wasn’t caught before they signed the contract.” (It isn’t unusual for celebrities to have a member of their management team sign contracts on their behalf.) It appears that what happened was that a This Is 42 staffer handed Gay a video release about 30 minutes before the Sydney event (that’s her estimate) and, thinking it was a release for that event, she didn’t sign it because she thought it was too broad. But as Desh explained to me in an email, it was a waiver for a separate video she had already recorded for This Is 42 in which she reacted to Hollywood depictions of black people. So the initial claim that This Is 42 didn’t have rights to the event video stemmed from this misunderstanding.

Things were too frenzied just then for Desh to worry about the legal threat, though — it was the day of an event that had been announced six months earlier, for which he and the talent were already at the Sydney airport, and there was still disagreement about the moderator. Desh appealed to Gay: What if he didn’t ask her about the “white supremacist” claim and agreed to not show the Sharia video again? Gay agreed to drop her objection to letting him host.

***

Everyone seems to agree that the second event went a bit smoother. Desh couldn’t resist asking a question about conservative Muslim gender rules, so he ended up showing a different video, this one about Iran. “I was being cheeky,” he admits, “but I find that rather problematic, that whole inaction toward what’s happening in countries like Iran, Indonesia, Bangladesh. It’s close to my heart.” The next day, Gay and Sommers left Australia, and Desh was able to exhale a bit. “I thought that was the end of it,” he says, “and at that point my lawyer had written to their lawyers,” explaining that This Is 42 indeed held the rights to the video of the events. “I didn’t hear anything from them for a little while.”

On April 11, This Is 42 released a trailer for a planned video editing together footage from both events — one that seems to use negative tweets about the events as a “you’re not gonna want to miss this” selling point.

At 8 a.m. on Monday, April 14, his time, Desh got a call from Trinity Ray, the president of the Tuesday Agency. Ray made it clear to Desh that the agency was quite serious about preventing the video’s release. Desh argued that the video actually made Gay look good — she was impressive. Be that as it may, Ray insisted, Gay still didn’t want it to be released and also asked Desh to take down the trailer of the event. Desh says Ray then offered to pay for Gay’s flights and accommodation in exchange for his agreeing not to release the video and to take down the trailer. Desh said he would consult with his advisers.

The next day, according to Desh and confirmed by the email chain shared by Ray, Desh received an email from Ray with a confidentiality agreement attached, dangling the prospect of future access to Gay if he agreed not to release the video of her events with Sommers. “Certainly, I know Roxane would be grateful for your concession and open to booking additional events with you here in North America or elsewhere if we can come to some terms on this matter,” it read. In his first response, Desh said again that he would consult his advisers, but a couple of emails later he officially rejected the idea of suppressing the video: “I have nothing but admiration and respect for Roxane, but I think the video should see the light of day. I do not think it is ethical for me to take any money. I want to stand up to the principles I believe in, what drove me to reach out to Kevin to pitch this event in the first place, to help the world have better, honest conversations in an ever-polarised world.”

Ray responded by saying he understood and asking if Gay’s team could at least see the video before it went up. He asked Desh to take down the trailer on the grounds that it was racist. “Our concern with the trailer is that frankly we believe it plays to the ‘angry black female’ stereotype and as such comes off as racist,” he said. “I know that’s not your intent here, but it has been hurtful.” Desh agreed to share the video with Gay’s team when it was ready and to make the trailer private but only after the full video was released.

Ray remembered the circumstances of the conversation that kicked off the email back-and-forth a bit differently: He said that the compensation came up only because Desh complained that he had lost money on the mini-tour and that the idea of North American events came up only because Desh revealed in the call a desire to expand into event planning there. Ray complained that both parties had agreed the conversation would be confidential. “He did tell me not to record the call where the offer was made but did not tell me the call has to be confidential per se,” Desh claimed in followup emails. “I have never publicly spoken about my dealings with a talent’s management in my entire career but then again I have never been threatened to be sued by one, either :-)”

One point of consensus among all the participants in this fracas seems to be that Desh was a bit blindsided by the intensity of what the mini-tour had wrought, both in its run-up and during the events themselves. “He reminded me of the Dev Patel character in Best Exotic Marigold Hotel — charming, enthusiastic, idealistic but a bit overwhelmed by events,” said Sommers. “He had a great success bringing the physicist Michio Kaku to Australia. He had imagined that a large appreciative audience would gather to hear two feminist writer-professors with very different ideas discuss their differences — and perhaps find some common ground. That turned out to be impossible.” That’s certainly true, and it’s also interesting, when listening to the event itself, to note the way its very structure and atmosphere, rather than nurturing real conversation, dumbed it down in, well, exactly the way Desh said it did in his analogy to terrible YouTube comments.

The best example came in a discussion of campus rape toward the end of the Sydney event. Sommers was explaining,

What worries me the most is that, to the extent that we have a serious problem, which no one here is denying, there’s actually a good study — it was in The New England Journal of Medicine — about how you could cut the numbers and how you could get it down of just untoward behavior and too much … and what they found was that girls are most vulnerable freshman year, and it has to do with sort of binge drinking and drunken parties and fraternities and all the things you could [The audience boos] … So they found they could cut the numbers substantially, and this was peer-reviewed, careful research. And the young women would take a course, and they would learn more about [More, louder boos] — Exactly! Everyone’s — Showing somebody how not to be a victim is not victimizing them. [Loud, angry jeering]

“Surely we can have a class that shows young men how not to victimize,” Gay responded, eliciting raucous cheers. A minute later, she reiterated that idea: “Really, all of these problems could be solved by men learning to not rape.” More cheers and applause followed.

I’m familiar with the study in question — I covered it when it came out. It was a sophisticated, carefully constructed approach centered on helping young women “assess risk from acquaintances, overcome emotional barriers in acknowledging danger, and engage in effective verbal and physical self-defense.” Yes, some of the tools might come in handy in alcohol-soaked situations, but that wasn’t really the focus. Rather, it was more on the risk of acquaintance rape and on a message any progressive feminist would agree with: Young women should be empowered to be outspoken in asserting their boundaries when they feel those boundaries are being threatened, but they’re all too often socialized to be polite or pliant instead. The program seemed to work. Young women who went through it were significantly less likely to face an attempted or completed sexual assault than those who were simply given a standard-issue sexual-assault-prevention pamphlet. Again, the available evidence suggests that young women who would have been sexually assaulted in the absence of this program weren’t, because of it.

But in Sydney, on a stage ostensibly dedicated to fostering meaningful conversation, everyone, the audience included, quickly manned the appropriate battlements, eager to show they were on the right side. For Sommers, it was about binge drinking and out-of-control campus culture, conservative bogeymen. For Gay, that was victim blaming, a liberal one. In a quiet bar or restaurant, with the journal in front of them and someone explaining exactly what the study found, it’s highly unlikely that either woman would have responded to it with anything but interest and enthusiasm and possibly some mild disagreement over the specifics. It prevented assaults, and everyone agrees young women should be taught to speak up when they’re made uncomfortable. But here, in a charged public setting where, not unlike Twitter, every utterance was met with immediate audience feedback, there was no room for that. Instead, the debate was dumbed down, almost immediately, to a hero-vs.-villain caricature: There was Roxane Gay, who is Good because she wants men to stop raping, versus Christina Hoff Sommers, who is Bad because she, on the other hand, blames women for being raped. As though Gay doesn’t want young women to speak up and say, “I don’t feel comfortable — please leave my room right now.” As though Sommers doesn’t want men to stop raping.

Despite the prolonged chaos and negotiation surrounding this tour, Gay said she isn’t worried about the video being released, as long as it’s unedited. “I have no problem with the video, unedited, being released because I did well in both debates and am pleased with how I represented my views,” she said. “The full, unedited video will, frankly, work in my favor given all the nonsense that has arisen around this event.” It sounds like there’s probably still some negotiating to be done between the two camps, given that This Is 42 plans on releasing a version in which footage from both events will be cut together sometime Wednesday, April 24, which as of this writing is just a day away.

Soon, at least, everyone will be able to decide for themselves what they think of the events. But still: This can’t have been what Desh Amila had in mind.