This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

I.

What Is Owed

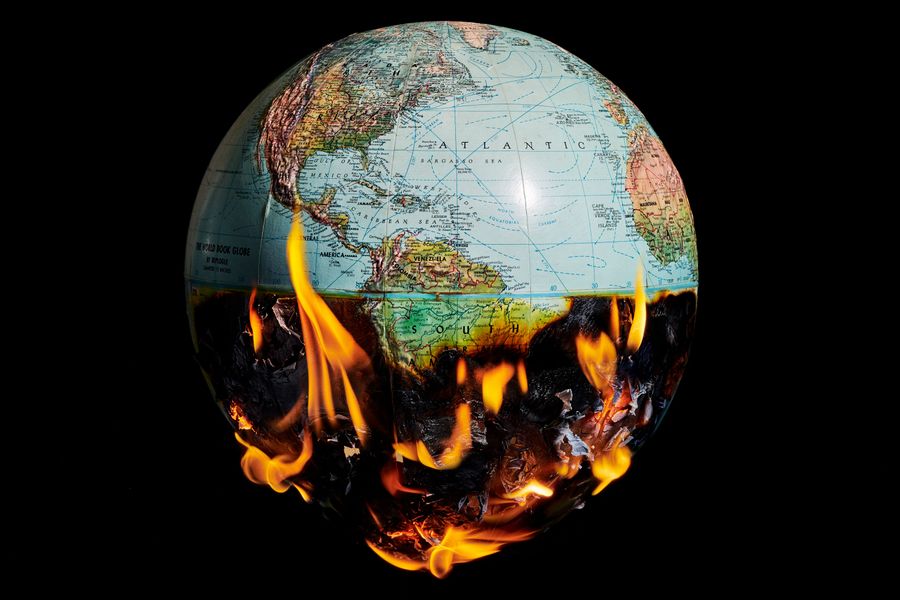

The math is as simple as the moral claim. We know how much carbon has been emitted and by which countries, which means we know who is most responsible and who will suffer most and that they are not the same. We know that the burden imposed on the world’s poorest by its richest is gruesome, that it is growing, and that it represents a climate apartheid demanding reparation — or should know it. We know we can remove some of that carbon from the atmosphere and undo at least some of the damage. We know the cost of doing so using tools we have today. And we know that unless we use them, the problem will never go away.

Carbon dioxide is a gas, but it doesn’t dissipate immediately like viral aerosols in the wind. It accumulates, thickening the atmosphere for centuries, which means that all the carbon that has been added to the skies since the advent of industrialization is still heating the planet today, and will be for ages to come, turning the Earth we have known into one we don’t.

Warming is often described as an ecological crisis. But there is another way to conceive of climate change: as a moral catastrophe, engineered by the sheltered nations of the global North in the recent past, and suffered by those, in the global South, least responsible for it and least prepared. The rich are rich today because of development powered by fossil fuels; the poorest today are those who have produced practically none of that pollution. But the atmosphere is as indifferent to the location of emissions as it is to motive; what matters is the tally of damage. Climate policy concerns itself primarily with future emissions trajectories: what can be done. But we have a climate crisis in all its urgency and brutality now because of legacy emissions: what has been done.

What has been done is this: Sixty percent of all historical emissions were produced in the lifetime of the average American, who is 38. Almost 90 percent were produced in the lifetime of our president. The Paris agreement of 2015 established a goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. That goal implies a carbon budget. We have already spent 89 percent of it.

Today, as hundreds of millions still lack electricity in the global South, 80 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions are being produced by the countries of the G20. Nearly half are produced by the world’s richest 10 percent, and a single transatlantic airline ticket yields one ton of CO2, more than the annual emissions of the average resident of sub-Saharan Africa. One recent study suggested that every four Americans could, in their lifetime, produce enough carbon to kill one person living elsewhere on the planet. Wealth can enable decarbonization now; with clean energy cheaper than dirty energy for 90 percent of the world, renewables are finally yielding viable dreams of global green prosperity. But all of industrial history has been governed by a different pattern: Growth has meant emissions, and emissions have meant growth. The climate crisis is the result of that history, as is the wealth of nations.

Since 1850, when anthropogenic emissions essentially began, the U.S. has produced 509 gigatons of carbon dioxide, according to a recent review by Simon Evans of Carbon Brief. That is by far the most of any nation in the world, a fifth of the total. China has produced the second most, with 284 gigatons, only about half the American total, though it has three times as many people and is often vilified by Americans as the great climate scoundrel. Third is Russia, with 173, followed by Brazil (113), Indonesia (103), Germany (89), India (86), the U.K. (75), Japan (67), and Canada (66).

In the U.S., where the term reparations typically encompasses both historical and current racial injustice, actual tabulations can get tangled in the messy, though intuitive, relationship between the two. (Ta-Nehisi Coates’s culture-changing essay on the subject from 2014 landed on a call to study the matter.) When it comes to warming, you don’t have to calculate backward from climate damages, which are shrouded in uncertainty until disaster hits. Instead, you can work forward from the more hopeful principle of restoration. That is the clarifying moral logic of climate reparations: One inarguable measure of responsibility for anything that’s been done is what it would take to undo it.

Technologies that can remove carbon dioxide from the air and begin to repair the climate do exist. We’re using them at infinitesimal scale, and staggering obstacles to their global implementation remain — but, usefully, these methods come with present-tense price tags. Climeworks in Switzerland is charging about $600 a ton. Other “nature based” approaches promise removal for as little as $10 per ton, though each has limitations and drawbacks. There are skeptics of engineered approaches, too, but most scientists and researchers believe that, given investment and public support, at some point over the next decade or two, the price of extracting and storing carbon by scalable technique will fall to about $100 a ton. An alternate method of tabulating damages is called the “social cost of carbon”; recently, economists Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern submitted that it was also $100 a ton.

From there, calculating the climate debt is just a matter of multiplication. By that math, what is owed is this: by the U.S., $50 trillion; by China, about $30 trillion; by the U.K., $8 trillion. In total, the bill would come to $250 trillion, more than half of all the wealth that exists in the world today.

These figures are a provocation — naïve, like many moral propositions. Carbon removal is not a one-click solution, as eager as the complacent consumers of the North are to believe in mirages of deliverance. It is more like the work of a century, and a planet, and much easier to imagine when contemplating the problem before a whiteboard wiped clean of politics and resistance than when planning an intervention in the real world. Reducing emissions by simple decarbonization — solar and wind and electric vehicles — is considerably cheaper. And talk of carbon removal puts the cart before the horse, since it would only be effective after a rapid transition to net-zero emissions: The more carbon we pump into the atmosphere, the harder the job it will be to remove it.

However naïve, the price of restoration is one way of calculating the climate debt imposed by certain people in certain places and times on other people in other places and times; that is, it is a way of articulating the scale of the ecological and humanitarian crime we are watching unfold, often pretending we are not perpetrating it ourselves. Working at the whiteboard, this would be the price of atonement.

II.

‘You Cannot Adapt to Extinction’

Vanessa Nakate is 24 years old. She was born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1996; since then, almost half of all of the emissions ever produced in the history of humanity have been put into the atmosphere. Sub-Saharan Africa, where by the end of the 21st century a third of the planet’s population is expected to live, is responsible for under 3 percent of that total.

Oladosu Adenike is 27. She was born in 1994 in Abuja, Nigeria, where in September lethal floods destroyed more than a hundred homes. In Lagos, floods cost an estimated $4 billion each year. In the Lake Chad region, warming is leading to armed conflict between farmers and herders, she says, driving a rise in “crime, kidnapping, and banditry” and contributing to a national epidemic of child brides — 20 million or more, according to UNICEF. She calls climate change “a pandemic that we cannot isolate from, that we cannot quarantine from.”

Disha Ravi is 23. She was born in 1998 in Tiptur, India, where by 2050, in even a moderate-warming scenario, the number of days each year when temperatures reach a threshold of lethality is expected to approach 100. A few hundred miles south, the number is expected to grow from about that level, where it already is today, well past 200.

“We have the whole package of the climate crisis,” Ravi tells me. “Like, name a disaster and we have it.” Tropical cyclones, the equivalent of Atlantic hurricanes, have hit the subcontinent from two sides nearly at once. “In Karnataka, my home state, we have a water crisis, we have drought,” she says. “In Rajasthan, again, we have drought. In Delhi, we have heat waves.” She mentions the flooding in Mumbai, underwater now for stretches every year, with recent rains bringing down an apartment building and, in the surrounding countryside, destroying whole villages. “There’s an increase in sexual trafficking when floods hit,” she says. “I would have not in my life thought that this would be seen as, like, an opportunity for sexual traffickers to traffic women. But people lose their homes, they lose their jobs, and they lose documentation. They lose life as they know it. They’re just struggling for money. And when the relief work that the government does isn’t enough, like most times …” Ravi trails off. “There’ve been millions of people who’ve died of bad air quality and millions more don’t have access to clean water. And we’re in a pandemic. Everyone keeps saying, ‘Well, wash your hands to prevent COVID from spreading.’ With what water? With what water are they supposed to wash their hands?”

At some point, observing the crisis from the global North, you have to ask yourself: Is a person in the global South a person to me? And if what the right answer demands of you feels extreme, consider what it would mean, in the midst of climate breakdown, to answer in the negative.

The total burden of climate change in the developing world is hard to quantify, not just because of the uncertainty that governs all projections of future warming but because the research on the poorer parts of the globe has been prejudicially thin. The picture we do have is grim. In northern Africa, according to a review by Carbon Brief, the average drought would last 20 months at two degrees Celsius of warming; heat waves would grow between sevenfold and tenfold across the continent. By the end of the century, even moderate warming could increase the number of Africans exposed to dangerous urban heat by a factor of 20. The Institute for Economics and Peace recently identified three belts of impending ecological disaster especially vulnerable to conflict and collapse: one stretching from Mauritania to Somalia, another from Angola to Madagascar, and a third from Syria to Pakistan.

Meanwhile, the global North may benefit in certain ways. Impacts in Europe are expected to be significant, but in Canada, Russia, and parts of Scandinavia, even high-end warming could more than triple per capita GDP, according to some economic analysis. Research by Marshall Burke and Noah Diffenbaugh shows that climate change has already exacerbated global inequality by as much as 25 percent. In India, they found, per capita GDP is 30 percent lower today thanks to warming. It is easy to skim past numbers like those, eyes glazed, but that is 1.4 billion Indians, already on average about one-third poorer than they would have been in a world without warming of just one degree. We are on track for three degrees, which casts the hope among the climate complacent that economic growth could be our best response to temperature rise — paying for adaptive projects like seawalls in the developing world — in a withering light.

“The droughts and floods have left nothing behind for the people,” Vanessa Nakate said last month in Milan. “Nothing except for pain, agony, suffering, starvation, and death.” She was addressing a conference of activist youth, giving what is perhaps the most memorable and vivid indictment of global leadership on issues of climate justice by any member of her generation. Onstage, she cited a World Bank report warning that 86 million could be displaced in sub-Saharan Africa; the 38,000 species on the extinction-risk “red list” maintained by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature; and the drought that has left Madagascar on the brink of “the world’s first climate-change famine,” in the words of the U.N. “Who is going to pay for Madagascar?” she asked. “Who is going to pay for the lost islands of the Caribbean and Pacific? Who is going to pay for the communities who must flee the Bangladeshi coastline? Who is going to pay for the thousands of species that fall off of the scientists’ red list and into oblivion?”

Nakate, who founded both Youth for Future Africa and the Rise Up Movement, is sometimes described as the continent’s Greta Thunberg. But while the two often work together, their rhetoric is subtly different, which may help explain — beyond reflexive prejudice and the casual indifference of the global North to suffering in the global South — why Thunberg has been so quickly canonized and Nakate relatively sidelined. Thunberg’s message is self-lacerating but also clinical: Look at the science, she says, and look at your own hypocrisy. Nakate’s message is a more direct indictment of western audiences: Look at what you are doing to us. This makes it all the more wrenching that she first gained real international recognition when the AP cropped her out of a January 2020 photograph of the world’s leading youth climate activists, the rest of whom were white.

“It’s not happening to them,” says Ravi, who was arrested by Indian police in February for distributing a tool kit for activists. “The person it’s happening to is us — the Black and brown people, the Indigenous people, the people of the global South. If the global North was actually feeling the impacts of the climate crisis, we would not be talking about the solutions as radical.”

In Paris in 2015, at the conference known as COP21, developing nations extracted promises of $100 billion in annual funding for themselves to be paid by the world’s rich. “That money is yet to be mailed,” Oladosu says, and today the poor countries of the world are spending five times more on debt repayment than they are on climate change. At COP26, the U.N. climate conference taking place this November in Glasgow, African negotiators are expected to ask for a tenfold increase in funding — to $1.3 trillion. When a South African diplomat recently proposed a smaller target of $750 billion, U.S. climate envoy John Kerry reportedly balked, unwilling to even discuss the matter.

“They think that’s economically not viable?” asks Ravi. “I’m just like, ‘Millions of people dying isn’t economically viable either.’ I think what the richer countries are going to do is push us, as the global South, under the bus to save themselves in the long run. That’s what they have been doing historically. And I don’t expect them to do better now. No.”

“How long shall the land mourn?” Nakate asked in Milan. “How long shall the farms lay in ruins? How long shall the herbs of every field wither? How long shall the animals and the birds perish? How long shall children be given up for marriage because their families have lost everything to the climate crisis? How long shall children sleep hungry because their farms have been washed away, because their crops have been dried up, because of the extreme weather conditions? How long are we to watch them die of thirst in the droughts and gasp for air in the floods? What is the state of the hearts of the world leaders who watched this happen and allow it to continue?”

She went on: “You cannot adapt to lost cultures. You cannot adapt to lost traditions. You cannot adapt to lost history. You cannot adapt to starvation. And you cannot adapt to extinction.”

“It’s time,” she said. “It’s time for our leaders to wake up. It’s time for our leaders to stop talking and start acting. It’s time to count the real costs. And it’s time for the polluters to pay. No more empty promises. No more empty summits. No more empty conferences. It’s time to show us the money.”

III.

The Radical Case for Removal

“There are two ways forward,” the Nigerian-American philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò wrote last year in Foreign Policy with Beba Cibralic. “Climate reparations or climate colonialism.”

Carbon removal was not mentioned in the essay. Instead, Táíwò and Cibralic proposed a radical reimagining of the global political order. There were two central planks: first, a legally binding mitigation policy, requiring the North to accelerate its emissions cuts and fund decarbonization in the South; second, open borders, or at least a dramatically more accommodating international refugee regime. Since writing the article, though, Táíwò — whose vital book Reconsidering Reparations will be published in December — has been thinking more and more about carbon removal. “If the revolution happens tomorrow, all of that carbon is still there,” he says. “We can’t moralize the carbon out of the air.”

The argument is intuitive. Even rapid decarbonization only blunts the impact of warming, stabilizing temperatures at levels long considered catastrophic. Removal could in theory restore more comfortable conditions, pulling the most vulnerable parts of the world back from the brink of ecological disaster and undoing some of the punishment that warming promises to layer on top of earlier legacies of brutality and extraction. Before philosophy, Táíwò studied questions in the social sciences: how to design trade policy, or education programs, or public health, in light of enduring injustices. “I’d been long since convinced that colonialism and slavery were central to the history of the last five centuries or so,” Táíwò says. “But one of the things that I learned along the way, or was increasingly convinced of, was that climate change is going to be central to the history to come. There was no way to game out how the politics and economies of the future were going to shift that didn’t run head first into the reality of the climate crisis.”

Most profoundly, carbon removal extends the promise of time. Since a hair-raising report from the IPCC in 2018, which called on the world’s governments to almost halve emissions by 2030, the timeline for action has seemed claustrophobically short. Carbon removal has been the way fossil-fuel companies have pretended to solve the insoluble math — promising future drawdown to offset ongoing production. Activists, understandably, have blanched, though their own ambitions almost certainly depend on the technology already: Keeping warming below 1.5 degrees is impossible without large-scale removal, according to the most recent IPCC report, and most scenarios delivering a relatively comfortable endgame require, in addition to 90 percent decarbonization of the world’s economy by 2050, 10 billion to 20 billion tons of carbon sucked out of the atmosphere and permanently stored, one way or another, every year thereafter. The number may be smaller if decarbonization proceeds more quickly, but almost certainly it won’t be zero.

Which is perhaps why a small but growing number of radical thinkers have begun aligning with technologists and technocrats, trying to reclaim removal, previously a rhetorical instrument of delay for the right, as a potential tool for justice on the climate left: For the same reason that it is often derided as a moral hazard, extending a leash to fossil-fuel extraction, it could also extend the political imaginations of those hoping and fighting for a sunnier future, so long as the direction of the technology was wrestled into the right hands. If the project of averting catastrophe must be completed this decade, one is forced to work with the power structures and institutions one has today. There just isn’t much time for a revolution. If the project could last a century or more, the horizon of political possibility glimmers with just a bit more hope. Because while carbon removal doesn’t much slow the need for decarbonization, it does recast what kind of repair and repayment might be possible in the century that follows net zero. In that century, we could, in theory, roll back the tape of destruction — to 400 parts per million in the atmosphere, where we were in 2014, perhaps to the “safe” level of 350, where we were in 1988, or even 280, the preindustrial average. Carbon removal at that scale is sometimes mocked as terraforming — a planetary renovation out of sci-fi. But over a century or two, you could terraform. It probably wouldn’t be utopian. But it could be progressive.

This is the view of Holly Jean Buck, a sociologist at the University of Buffalo and the author of two incisive books on related subjects: After Geoengineering (2019) and this fall’s Ending Fossil Fuels. “If the capacity exists, then there’s a moral responsibility to use it,” she says. “And I don’t think that the entire cost needs to be borne by this generation, necessarily. You can imagine that this generation contributes a part, and so does the next one, making a kind of bell curve, extending a couple of hundred years into the future.”

Buck has impeccable left-wing bona fides, among other things having collaborated with the radical Swedish intellectual and would-be ecoterrorist Andreas Malm, whose recent book is How to Blow Up a Pipeline. For all its searing moral clarity, Buck’s writing is also an effort to help recalibrate the perspective of the climate left toward more pragmatism and broad-mindedness in part by “changing the time horizon” from immediate to “multi-century,” she says. “People often think that it’s hopeless or that, if we don’t do something in the next ten years, all is lost.”

In politics, a sense of urgency often yields to hardball, if not quite absolutism, and climate advocates in the global North have long been suspicious of policy delay, particularly anything that smells like quick-fix solutionism — a list that in addition to carbon removal includes adaptation, nuclear power, solar-radiation management, and geoengineering. Like Buck, Táíwò regards that as a form of technological determinism. He is less focused on the problem of moral hazard and more on how to reverse it through new approaches to governance: public ownership of power, for instance, or community control of carbon removal or adaptation projects. “I guess I sound like the most orthodox materialist, but it really comes down to how capital is distributed,” he says. “It’s just so clear to me that carbon removal is squarely the kind of thing that fits into the reparations framework. And I think it’s been a real failing of the environmentalist left — and a real failing, perhaps, of those of us who are in the First World — that we have allowed the nation-states we live in, alongside the fossil-fuel companies, to obfuscate this issue to the extent that it’s been obfuscated.”

In part, Táíwò says, that reflects Americans’ basic difficulty with confronting their own culpability. “On a psychological level, I think people want a clear villain,” Táíwò says. “And part of the stance of opposing a villain is distance, right? The villain is somebody else, the villain is over there. And so if we’re in a world where ExxonMobil is the primary bad actor — as opposed to, say, the United States — the only test you have to run your rhetoric and political positions through is whether or not it succeeds in opposing the oil and gas company. You don’t have to ask the further question about what the geopolitics of your commitments are.” One shouldn’t ask why the oil majors are talking about carbon removal, he says, but why so many scientists are.

“There’s been many debates over the past few decades about which solutions are the real solutions and which ones are distractions,” he says. “That is obviously important,” he acknowledges, but gives the impression that “there’s some particular thing or some small list of things that we could do to get us out of the crisis” and that makes all other potential solutions unacceptable — diversions at best and often just excuses for continued extraction and emission.

That was the logic of a May report by an environmental-justice working group convened by the White House, which put together a list of destructive climate policies that included things like fossil-fuel extraction and highway buildout but also carbon capture, direct air capture, nuclear power, and even research and development of any kind—advising that everything on the list be excluded from federal climate policy.

“A lot of the people making those criticisms — of the so-called moral hazard of adaptation as a distraction from mitigation or carbon removal as distraction from mitigation — a lot of those people call for totally transformative changes to our social system, to our energy system, to our political system,” Táíwò says. “And that’s when they’re right. They should believe that. And what that means is there’s actually a lot of things that we have to do. None of them are substitutes for the other things that we also have to do.”

“The moral case is pretty basic,” says Buck. “The question is, ‘What sort of people do we want to be?’” Contemplating the damage already done in the developing world by the global North, it might be hard to answer that question optimistically, though Buck does. “I think that most Americans want to be people that clean things up,” she says. “They don’t want to have their legacy be one of trash.”

IV.

The Geopolitics of Drowning

Probably, you have only begun to panic about climate, if you have at all, in the last several years. But the global South has been trying to talk to the wealthy nations of the world about warming in the language of existential injustice for much longer. “We have been asked to sign a suicide pact,” the Sudanese diplomat Lumumba Di-Aping lamented at the 2009 U.N. Copenhagen Climate Change Conference, calling two degrees of warming “certain death for Africa” and a brutal form of “climate fascism,” imposed by the wealthy, high-emitting countries of the world on those who’d done the least to manufacture the crisis. “What is Obama going to tell his daughters?” Di-Aping asked. “That their relatives’ lives are not worth anything? It is unfortunate that after 500 years-plus of interaction with the West, we are still considered ‘disposables.’”

At the same conference, Mohamed Nasheed — a former journalist, dissident, and political prisoner in the Maldives, who had recently become the low-lying nation’s first democratically elected president — famously excoriated the assembly: “How can you ask my country to go extinct?” In 2018, having been driven from office by opposition forces staging a soft coup, Nasheed took the stage at a follow-up conference in Poland and reiterated that, however indifferent the world’s powerful nations might be to the fate of the most vulnerable, “we are not prepared to die.”

Today, in the run-up to Glasgow, and six months past an assassination attempt by IED, Nasheed remains clear-eyed. “We all know the Paris agreement is in default,” he says. “1.5 degrees — we aren’t anywhere near that.” But he has also grown more circumspect and strategic, reluctant to push existential rhetoric or demand reparation. As part of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, he is calling for a handful of more targeted interventions: recommitment to capital transfers, large-scale debt restructuring managed by the IMF, a declaration of climate emergency. (A previous demand, for a U.N. special rapporteur for climate rights, was recently fulfilled.) “When the developing countries start framing these negotiations in very hostile language — in anti-colonial or anti-imperialism language — then we lose a bit of receptiveness from the developed countries,” he says. Instead, he says, he hopes that “we can start talking about this in another language, and say, ‘Yes, of course what’s done is done’ — but not ask for the pound of flesh in return.

“I can’t ask that. Because you did not invent the internal-combustion engine to do harm. It was done in good faith. You wanted to rid yourselves of disease, you wanted to earn a good life for yourself. Yes, of course there’s important injustice in the process. But, you know, I find it always difficult to move forward with that kind of hostility, with that kind of bitterness,” he says.

“If you’re looking for bitterness, I have been tortured twice. And just recently I became a victim of an assassination attempt. If I’m going to be hung up with that, with my past, it’s going to be very difficult for me to go forward,” he adds. “All the wrong that’s done, it’s done. And we need concessions from people. We need people to understand and people to agree. That’s true. But we also need to go on. We need the future.”

Saleemul Huq sees the future, too. The director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development in Dhaka and a senior associate at the International Institute for Environment & Development in London, the Bangladeshi scientist and climate advocate is, he says, “increasingly pessimistic” not just about the prospects that Glasgow could solidify and extend the gains imagined by the Paris agreement but that any “global agreements” on climate might make much difference. “We have just entered what I call the era of loss and damage from human-induced climate change,” he says. “Every single day, somewhere in the world, a weather extreme is going to be broken. Sometimes it’s going to be shattered, not just broken. The heat dome that took place in Canada — the extreme heat record was broken on a Monday and then that was broken on a Tuesday and then that was broken on a Wednesday and then that was broken on Thursday. By the time it ended, it was five degrees above anything that they’d had before. That’s a record-shattering event, not just a record-breaking event. And we will see that thumping, hard and fast, every year — somewhere in the world, every single day, from now on. 2021 is going to look, in hindsight, like a very nice time.”

This has been the year in which the second-greatest number of acres ever burned in California, after last year’s record; when hundreds died in the Texas cold snap, and again in the model-defying Pacific heat dome, and again in torrential flooding in Germany. “Loss and damage is for everybody now,” Huq says. “More than 50 people lost their lives in New York and New Jersey in the floods from Hurricane Ida. It’s not just poor countries and poor people anymore. It’s everyone, everywhere. And in a very real sense, it’s the children of the people making decisions today that are going to suffer. Forget about poor people in poor countries — that doesn’t move the dial an inch. Rich people harming poor people — they don’t give a shit. Rich people harming their own children — they’re beginning to think about that.”

By reputation, Huq is not a fatalist. Internationally, he may be known primarily as an advocate of adaptation, a practical-minded Bangladeshi scientist often seen celebrating the success of his country in preparing for and responding to natural disasters that just a short generation ago would’ve wreaked absolute havoc — and still do next door in Myanmar. He sees “an insurmountable gap,” though, between the stated goals of the international climate community, which remains at least rhetorically committed to a 1.5-degree target, and even the nominal pledges it has made thus far, which, if implemented in full and without complication, would only just nudge the planet below three degrees of warming. He mentions a recent speech by Greta Thunberg — “Build back better, blah, blah, blah. Green economy, blah, blah, blah. Net zero by 2050, blah, blah, blah” — and says, “I’m calling COP26 the first blah, blah, blah COP. It’s going to be all blah, blah, blah.”

“The current generation of leaders is totally incapable of rising to the occasion,” Huq says. “And it’s good to focus on climate justice as the issue. It used to be environmental issues, the emissions of greenhouse gases, and then adaptation and helping the poor to adapt. Now it’s about justice, and that’s right. But to me, even the phrasing of climate justice is inappropriate phrasing. To me, the issue is climate injustice, which is absolutely manifesting, staring us in the face. It’s wrong: Rich people are harming poor people — poor people around the world but also poor people in their own countries. You know, the people who died in New York were poor New Yorkers, not rich New Yorkers. The people who lost their lives in New Orleans, from Hurricane Katrina, were all poor Blacks living in the Ninth Ward. Not a single rich New Orleans citizen died. And so there’s a huge discrepancy between who suffers and who causes suffering. Across the board, globally, the rich cause suffering and the poor suffer.”

“It’s like when Jane Fonda visited Vietnam during the Vietnam War and said, you know, ‘What can I do to help you?’” Huq says. “The Vietnamese said, ‘Get your own government to stop bombing us.’” When it comes to climate change, “that’s the message from the poor countries to the rich countries: ‘Stop bombing us.’”

V.

Engineering a Century

Technology can’t save us, not alone at least. Only humans can. In 1988, when James Hansen first warned Congress about the risks of global warming, all that was required to keep temperatures below 1.5 degrees was gradual decarbonization unfolding over more than a century. We probably wouldn’t have even had to hit net zero by 2100. Now, given how much carbon has been blithely added to the atmosphere since, we only have until 2050, and we are staring out at the prospect from the vantage of an emissions peak almost twice as high.

In the meantime, as we kept burning, the rapidly falling price of renewable energy has made urgent decarbonization finally plausible, pulling relatively more comfortable climate futures into the realm of plausibility as well. Today, when we say “business as usual,” we don’t mean 4.5 degrees Celsius of warming and a quintupling of global coal use; we mean about 3 degrees, the end of coal, and the electrification of almost everything. But while worst-case scenarios seem considerably less likely than they did just a few years ago, globally, a perverse feature of that progress is this: We may have eliminated, or at least reduced the likelihood, of civilization-shaking warming in the global North without managing sufficient progress to spare the global South, where the same temperature levels look far more catastrophic.

To those on the climate left, this is perhaps not a coincidence. Nor is it a surprise that, with the tools we need to manage the vast majority of the energy transition, we are nevertheless making such slow progress today. If you have spent the last few years dreaming of sudden climate deliverance, in which devastating warming is averted by some genius at a whiteboard or some innovation ex machina, you should know that the tools we need are already here. The problem isn’t magical tech; we have that in the form of renewable energy. The challenge is deploying it at scale in the face of politics, the fossil-fuel business, NIMBYism, regulatory capture, shortsightedness, and basic social narcissism and collective dysfunction. You don’t solve that at CalTech or with AI.

Carbon removal is a second miraculous technology, one that looks even more like the solutionist fantasy. But it is expensive, lacks any market at all, and even maximally deployed would not eliminate the need to deliver the first set of technologies as rapidly as possible. Which is why it is more or less impossible to find a single advocate of carbon removal outside the fossil-fuel industry who believes the technology enables a slow-walk of a global fossil-fuel phase-out. “It strikes me as somewhat absurd that people are confident that we will withdraw climatically substantial amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere while we can’t even stop our collective selves from burning fossil fuels and cutting down forests,” says Ken Caldeira of the Carnegie Institution for Science. And yet without removal, he says, it would take perhaps a million years for the climate to return to its preindustrial state.

“Imagine you had Kim Stanley Robinson as the benevolent philosopher-king of the carbon-dioxide-removal universe,” says Danny Cullenward, a climate economist and the policy director of CarbonPlan, a research NGO. Robinson is a science-fiction novelist and the author, most recently, of The Ministry for the Future, which has lately joined Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower on the shelf of novels most beloved by climate activists. Ministry, written in the environmental despair of the Trump years, offers a bleak quasi-utopia: A gruesome heat wave devastates India, killing millions and initiating a geoengineering project to artificially cool the planet; the titular ministry is formed, under the auspices of the Paris agreement, devoted to the principle that future generations have rights equal to those alive today; and an alliance of technocratic central bankers introduce a digital “carbon coin,” minted whenever a ton of carbon is removed from the atmosphere as an enticement and reward.

Large-scale carbon removal “could be necessary,” Cullenward says, especially if managed, as Robinson imagines, as a public good. But even in a boom market for carbon offsets and removal, Cullenward isn’t especially optimistic, at least in the near term, when the halting, muddied progress of climate action is less likely to be solved by new tech than duplicated by it. “The scale of the problem, the scale of the science, the trajectory of where we are, what we know we need to do — it’s increasingly clear and frightening. And the amount of snake oil that’s out there, the ideologically partisan takes on complex science, the bad behavior, borderline fraudulent — it’s a really ugly time,” he says. “Just the amount of bullshit that’s out there is off the charts.”

The bullshit begins at the highest levels. Starting slowly at the outset of the pandemic, then in growing waves in the run-up to COP26, the nations of the world have been announcing unprecedentedly ambitious pledges of decarbonization, with two-thirds of global emissions and global GDP nominally committed to “net zero,” and most states of the North circling 2050 as the end date of their fossil economies. But the word net is doing a lot of work: Most of the pledges rely on large-scale carbon removal deferred far enough in the future you can make just about any claim about capacity you’d like. This is how the countries of the world can nominally pledge to rapidly decarbonize while also, according to the U.N., planning to expand fossil-fuel production through 2040; and how Saudi Arabia, for example, can promise net-zero carbon by 2060 while planning to expand fossil-fuel use by as much as 45 percent by 2030. On top of which, the country doesn’t even have to count all the emissions it’s exporting, primarily in the form of oil, which is quite an accounting trick for a petro-state.

The accounting is probably even more clever, which is to say more pernicious, in the corporate sector. According to Science, half of the world’s 52 largest oil and gas companies have made net-zero promises, but only two were in line with the Paris agreement; outside the fossil-fuel sector, in the booming market for carbon-offset credits, as much as 90 percent of those sold fail to work as promised. Like many others working on carbon-removal research these days, Cullenward is especially frustrated by what he calls the “magical thinking” of these “nature-based solutions,” such as tree planting and soil management. “It sort of evokes this happy win-win framing, and it actually belies what’s been going on,” he says. “It’s been a tool for cognitive dysfunction on climate, and it’s been an excuse not to take action for a lot of people.”

You may have heard of the “trillion trees” proposal, based on a since-discredited paper, or the broader mission to replant the world’s forests to save the planet. But while nearly every carbon-removal expert would acknowledge the value of protecting trees and soil, forests require enormous amounts of land, much of which is required already for food production. New forests are often poorly designed when being planted for use as offsets, and poorly managed for carbon removal once they are. In some parts of the global South, where these projects are often sited, they’ve colonized whole local ecosystems and economies, displacing other opportunities. In others, existing tree plots are sometimes sold not as true carbon removal but only “avoided emissions,” which is to say forgone deforestation — you don’t take any carbon out of the air and agree not to release what’s stored in the trees already by cutting them down. (This means you’re not really offsetting anything.) And trees don’t store carbon permanently but only as long as they live, which is increasingly problematic when more and more of them can be torched by wildfire, as were Microsoft’s carbon offsets this year in Oregon’s 400,000-acre Bootleg blaze. In this, they are not all that unlike the carbon-dioxide embedded in Coca-Cola, much of which was probably pulled out of the air but will get released there again as soon as you open the can. All told, wildfires around the world have released about five gigatons of carbon into the air so far this year — more than the U.S. economy as a whole produces annually.

More durable and scalable methods, like direct-air capture and geologic storage, aren’t perfect either. On top of the moral-hazard issue, they’re often faulted for their cost, engineering challenges, intense energy demands (with some carbon capture requiring temperatures of 800 degrees or higher), and land use. Other methods — like enhanced mineralization, using crushed rocks to draw CO2 from the air; kelp farming, featuring massive underwater forests; or ocean alkalinization, whereby acidification of the seas is reversed — remain too much in the research phase to count on in the short term. They also lack any genuine market beyond the voluntary one called into existence by climate guilt.

And yet every single workable pathway even to climate stabilization requires some amount of carbon removal. How much? Last year, a large consortium of academics assembled a comprehensive carbon-dioxide-removal “primer,” led among others by Jennifer Wilcox at Penn, who had been the head of the World Resources Institute’s carbon-removal program and is now Biden’s head of carbon management at the Department of Energy. In it, the group tried to calculate just how big a job carbon removal had to be, given that while we have a good idea how we might decarbonize some things — from electricity to automobile transit — other things will continue to pollute. (There’s no green way to fly a passenger jet just yet.) Taking that last chunk of carbon out of the air with nature-based solutions, the consortium suggested, would require land several times the size of Texas; doing so with direct-air capture would require an enormous amount of energy at a time when renewable power is likely to still be limited. The group’s optimistic overall assessment was that between 1.5 gigatons and three gigatons of carbon would have to be handled by removal.

The biggest carbon-capture facility today can process just thousands of tons a year. When it opened to much fanfare in September, NASA scientist Peter Kalmus calculated that, in a year, it could eliminate three seconds’ worth of global emissions. Which makes the necessary scale up like a vertical rock face, even if we aren’t expecting “climatically significant” removal until 2050 or so. “If we can’t get some millions of tons of carbon removal this next decade, we don’t stand a chance to get to gigatons by midcentury,” Wilcox says. “Time will tell. If we continue to fail at the decarbonization we need to do and the carbon removal that we simultaneously need to do now, we’re not going to have a chance to restore it.”

Intuitions of end-times call forth evangelists of all varieties, and Julio Friedmann is one of direct air capture’s most enthusiastic. Under Obama, he had Wilcox’s job at DOE; now he’s a senior research scholar at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs and works with CarbonDirect as well, where he is an adviser. On Twitter, his handle is @CarbonWrangler. He wants us to set our sights very high — not at the roughly 40 billion tons of carbon now emitted each year but at the trillions of tons emitted up to this point. “At the end of the day, a moral framework would require climate restoration to — well, the most moral position is preindustrial, which is a lot of work,” he says. “Even getting to 350 parts per million, that is a trillion tons of work. But these are the kinds of numbers we have to get comfortable with.” On the eve of COP26, the U.K.’s Climate Crisis advisory group, an independent research organization, made the same recommendation: that the developed nations of the world commit to funding carbon removal sufficient to bring levels down to 350 ppm.

There are obstacles to such a rollout, as Friedmann acknowledges. But cast your imagination far enough into the future, he says, and the limitations are all essentially political. “At this point, you will have engineered solutions that have a very small footprint,” he says. “In 2045, with direct air capture at $150 a ton, run by a nuclear-power plant. That’s 1,000 times less land than trees.” The ultimate test is storage capacity, but for Friedmann and many other carbon-removal advocates, the storage capacity of the geosphere of deep Earth is effectively unlimited. He estimates that saline aquifers have a storage capacity of 10 trillion to 20 trillion tons of carbon dioxide. Mineralization, he guesses, “is 10,000 times larger than that — 100 quadrillion tons of capacity,” many multiples of what even a full restoration of the preindustrial climate would require. “We’re not limited by the physics.”

And we shouldn’t be limited by our imaginations, either, Friedmann says, working to remove only that amount of carbon we know we won’t be able to deal with otherwise. The models that suggest five gigatons a year or fewer, “those models assume success on everything,” he says — success on cleaning up the grid and all-electric vehicles globally and zero-carbon shipping and clean steel mills and a million other things than need to go green. “Just assume,” Friedmann says. In those models, carbon removal is still needed at the gigaton scale, but of course slower progress could mean more need for removal. “It’s the last wedge,” he says, “But it’s more than just that. It’s the backstop. If we fail at anything else, we can just do more than that. We have to do everything as hard as we can as fast as we can. But if we fail at anything, then we have a backup plan. The backup plan is direct air capture. It’s the only backup. Literally it’s the only lifeboat.”

At DOE, Wilcox is trying to help manage the scale-up through targeted public investment and support. “If the government just said, ‘We’re going to buy 50,000 tons a year and double that for ten years,’ then by the end of ten years, they’d be buying 10 million tons of CO2 removal every year,” Friedmann says. “That would be enough to create the market. They did that with solar panels, batteries, with nuclear reactors, with LEDs, also with flat-screen TVs and semiconductors. Government procurement is a way to get these things to market — they create whole industries this way.”

“And then at some point there’s an intersection where the engineered solutions are cheaper and more widely available than the nature-based solutions,” Friedmann says. “If we’re optimistic, it’s 2035; if we’re pessimistic, it’s 2060. And at that point, whether or not we restore the climate is entirely a financial and moral decision. Period. Nothing else you need to know. The question is just, How much do we want to spend to reverse the damage we’ve created? And that is an ethical and philosophical and political decision. It’s not a technology question or even an economics question. Because we will have all the means we need to restore our climate.”

“There’s no mystery about whether this is doable,” Friedmann says. “The answer is ‘yes.’ And if we spent enough money now on abatement and reduction and removal, then we could actually hit 1.5 degrees. That is still correct. And then we could repair the damage. We could clean up our world.”

But capacity is not sufficient, as the maddeningly slow progress elsewhere shows. “To solve climate is an inherently collaborative effort and inherently born of generosity,” Friedmann says. “We need to cultivate generosity with as much determination and deliberateness as we cultivate technology, finance, and policy. Because all of this is premised on a level of generosity and morality we have not witnessed much in humanity. This is the core problem: that it will take unprecedented generosity on the part of human beings.”

“What does unprecedented mean?” he asks. “More than we need a whole bunch of direct-air-capture plants, we need a lot more pope.” He mentions Pope Francis’s climate activism, the Marshall Plan, the need for “North-South redress,” and a system of global governance for carbon removal beyond anything the world has ever managed — a hope that amounts to stacking miracles on top of miracles. “But it’s all built on this notion of generosity,“ he says. “The idea of climate restoration is lunacy until you have that too.”

More on climate change

- The New Global Climate Deal Is Mostly Hot Air

- King Charles Forced to Deliver Speech He Hates

- Scenes From a Flooded New York