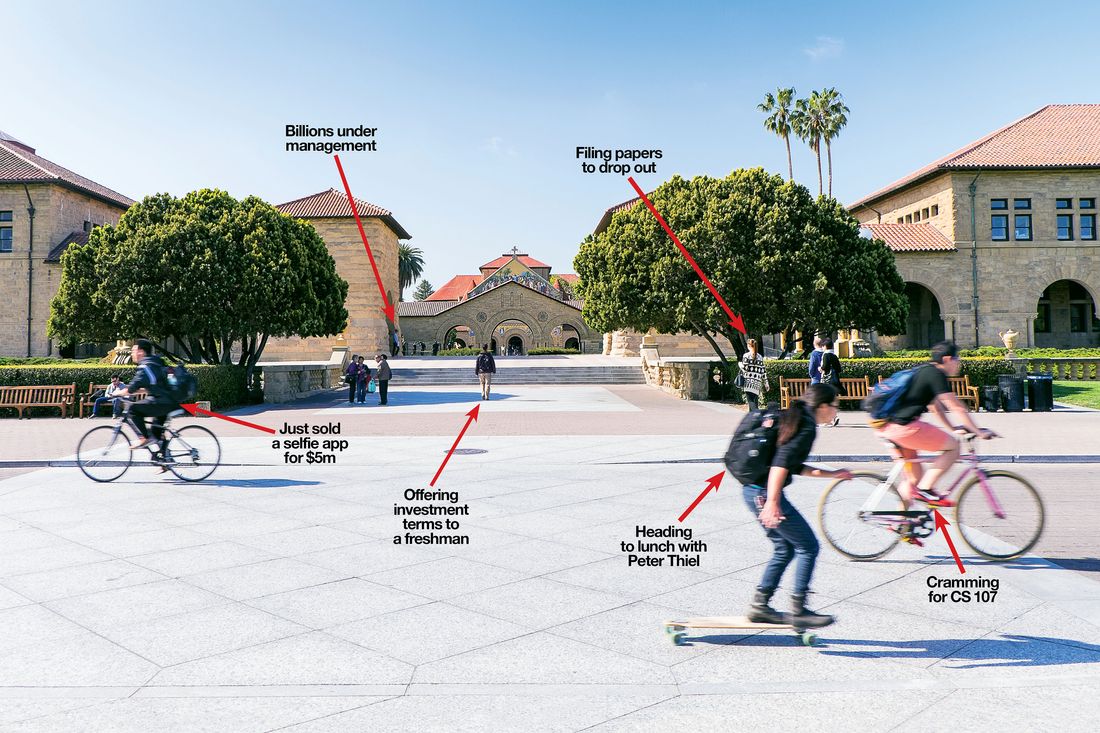

Google was founded by two Stanford graduate students, Instagram by two Stanford alumni, Snapchat by a Stanford dropout. WhatsApp, Netflix, LinkedIn, Yahoo, and Hewlett-Packard were all founded by onetime Stanford students; the earliest investors in Facebook and Amazon were Stanford graduates. Even Elizabeth Holmes, symbol of Silicon Valley self-delusion and fraud, was a student at Stanford when she dropped out to found Theranos. About the only two famous tech founders with no immediately apparent Stanford connection are Steve Jobs and Bill Gates — though is it a coincidence that each had a daughter attend the school?

Stanford, nestled south of Facebook and west of Google, is more than a kind of finishing school to the burgeoning independent commonwealth of tech. It’s already to the 21st century what Harvard, or maybe the University of Chicago, was to the 20th: the institution that grooms an elite class for power and imbues it with the reigning ideology. And for the students destined to rule over megaplatforms and other digital fiefdoms, Stanford can be less a college than a kind of incubator or accelerator — a four-year networking opportunity for the next Systrom, Spiegel, or Thiel, as everyone who goes there knows. “I don’t remember there being that much emphasis on serving others or what is the broad philosophical points of a Stanford education,” a political-science major from the class of 2017 told us. “It really always felt like it’s that gold mine, like you’re just there to find that random idea and hop on that train and have $100 million by the time you’re 30.”

No wonder, in that case, that Stanford has been the “dream school” of both parents and high-school students nearly every year for a decade, according to Princeton Review surveys, or that it boasts the lowest acceptance rate among major universities. This may seem like a recent development — and only over the past decade has the school gone all-in on an ecosystem of startup-supporting programs, turning classrooms into job fairs and students into entrepreneurs-to-be, and effectively handing the keys of the campus to venture capitalists. But it’s the realization of a long-term project begun in the 1950s by then-provost Frederick Terman, who sought to expand what had been a western backwater into an academic powerhouse by creating a virtuous cycle of growth: The school would encourage students to become entrepreneurs, and those entrepreneurs, once rich, would give back to the school. Terman, known as the “Father of Silicon Valley,” was an originator of the entrepreneurial, metrics-obsessed attitude that became the Valley’s defining ethos; at graduation ceremonies, he would take notes on the back of his program about which departments were producing the most doctorates.

Today, it’s hard to deny that Terman’s project has been a roaring success — for Stanford, at least, if not for equal income distribution in the U.S. Between 1939, when Terman set up William Hewlett and David Packard in a Palo Alto garage, and 1998, when Sergey Brin and Larry Page dropped out of the graduate computer-science department to pursue their new search engine, Stanford’s endowment increased by more than a hundredfold. But in the 20 years since Brin and Page left Stanford, the engineer-entrepreneur mind-set has shifted. Once, companies like Hewlett-Packard, Sun, Cisco, and Google brought the school’s academic research to market and therefore relied to varying degrees on the institutional support of Stanford — whether through the encouragement of administrators, the use of its wired-network infrastructure, or even the relicensing of intellectual property. The most important support system today is the network of people — and cash — who now populate and surround the institution, hunting for investments.

No one has noticed this more than Stanford students themselves, many of whom, it should be said, don’t like that their school has been so thoroughly penetrated by money and ambition. Of course, many more are turned on by it, as would not surprise anyone who has been following the recent “Varsity Blues” college-admissions scandal, which gives a clear sense of just how desperate American high achievers are to secure even the tiniest sliver of additional advantage. “There were probably one in ten or maybe one in five people at Stanford who are really interested in technology, who were doing it for reasons that I would consider pure,” one former engineering student complained. “I think the remainder were strictly in it to get rich and 20 years ago would have worked on Wall Street.”

To Stanford’s credit, some of the fiercest critics of the university’s most venal tendencies have come from within, like the early Holmes antagonist Phyllis Gardner, a professor of medicine at Stanford, or the M.B.A. student Adam Allcock, who went public with his discovery that Stanford’s business school was granting financial aid to students based on their perceived worth to the school, not their need. The whistle-blower whose information ultimately revealed Elizabeth Holmes’s fraud was a Stanford graduate — and the grandson of Hoover Institution fellow George Shultz.

If you’re cynical, though, you might want to just keep quiet. The guy sitting outside Coupa Café in the fleece vest might be an engineering professor, or he might be a VC. He might even be both: At Stanford, professors don’t just introduce you to potential investors; they often invest in student projects themselves. Want to impress those guys, bag yourself a big seed round, and escape into billionairedom? Read on. —Max Read

Boot-Camp Syllabus: What Every Prospective Evan Spiegel Should Know

No. 1: For ambitious entrepreneurs, Stanford isn’t just a college; it’s the mother of all tech incubators.

“I’m pretty sure I’ve heard of more friends starting companies than have gotten mononucleosis.” —Julian Alvarez, class of ’17, M.A. in philosophy ’19

“By the time you got to 200-level classes, sometimes your classes were fully or partially funded by companies. In CS 210, a class where you built applications in partnership with companies, after the second quarter of working on the project, you could fly out to present to them (if they weren’t located in the Bay).” —CS major, class of ’16

“VCs actively reach out to students who are known to be very good CS majors.” —Symbolic-systems major, class of ’17

No. 2: For start-ups, there’s money everywhere.

“At one CS event, I noticed that there’d be students talking about some app, and in the back row there’d be these dudes in those Patagonia vests, talking about funding.” —Psychology major, class of ’17

“There was a panel of VCs in one of my classes. A VC literally wrote a check for $10,000 on the spot. We were just like, ‘What just happened? What even is that? Are there terms with that?’ ” —Danielle Pensack, M.B.A. ’19

“You’d see VCs hanging out outside Green Library all the time, trying to see what was going on.” —Mechanical-engineering major, class of ’16

No. 3: Which makes for a pretty intense, strange campus.

“We had a saying — the ‘duck syndrome.’ Everyone looked fine on the surface, but we were all swimming hard as ever under the water to keep ourselves both afloat and moving forward. It’s 100 percent accurate of what freshman year was like.” —CS major, class of ’16

“I think duck syndrome is crap … To be stressed and unhappy and mentally unhealthy isn’t something you should brag about. But if you heard about somebody doing something really cool and you felt insecure about it, you were like, ‘Well, I stayed up all night and am really stressed out and unhealthy, so I’m doing okay.’ It was cool to be busy and stressed and overworked. It was something that you did to validate yourself and your worth.” —Alina Utrata, class of ’17

“Somebody pitched me their stupid app while I was taking a shit. This group of three students knocked on my stall and asked if I was almost done. And I didn’t reply, finished my business, and went out, and they were waiting for me. They’re like, ‘Hey, sir, can you give us feedback on this app we’re doing?’ ” —Psychology major, class of ’17

No. 4: So, first, drink this tea.

Everyone drinks boba tea, though Soylent is definitely a thing among the nerdier engineer set.

No. 5: Wear this shirt.

“A few years ago, half the school had a SAVE THE SHIRE Palantir T-shirt even if we knew nothing about the company, just because they were giving them out for free so much.”

No. 6: Pick your major wisely.

If your founder god is … Joe Lonsdale and Stephen Cohen (Palantir), Brian Acton (WhatsApp), Reed Hastings (Netflix), Leonard Bosack and Sandy Lerner (Cisco), or David Shaw (D.E. Shaw) ➽ Go for computer science.

And here’s where the rubber hits the road: CS 107*

All computer-science majors start with the same sequence of classes, the most important of which is CS 107: Computer Organization and Systems. After you get through 107 (and add it to your résumé on Handshake), you might already start getting recruitment emails from companies who see completing 107 as “the time when [a student] can feasibly join any dev role at entry level,” as one student put it.

“It was very much a moment-of-truth class for me. I had to take it twice. The first time was during a quarter when I was already struggling, and it totally crushed me. The material seemed absolutely impenetrable. My second try, I treated it very seriously as an obstacle that would demand everything I had. That time, the experience was totally different; it felt like a series of doors unlocking.” —CS major, class of ’18

*Since so much attention has been paid to CS 107, companies looking for an edge are now starting to keep an eye out for CS 110, the next class in the sequence.

If you’re emulating … Reid Hoffman (LinkedIn), Marissa Mayer (Google, Yahoo), or Mike Krieger (Instagram) ➽ Symbolic systems is for you. (Yes, that’s a real major, mixing big-picture theory and programming practice)

If you worship … Kevin Systrom (Instagram) ➽ Try management science and engineering.

If you’re more into … Bill Hewett and David Packard (HP) or Jerry Yang and David Filo (Yahoo) ➽ They all picked electrical engineering.

No. 7: Then meet (and brownnose) the faculty.

David Beach

Beach is the longtime leader of the cutting-edge Product Realization Lab, which is basically MythBusters on steroids. In 2011, Beach told The Stanford Daily that about 40 percent of the engineering staff at Tesla were PRL alums. “His top students and his favorites got introductions or really plum jobs at Apple hardware or other design studios like Ideo,” a mechanical-engineering major from the class of ’16 said.

Mehran Sahami

Widely known by his first name, Sahami is beloved and famous primarily as the fall-semester teacher for CS 106A, the most widely taken class in the entire university. He has also, on rare occasions, invested in student companies; maybe the one black eye on his reputation is that he invested in Clinkle, a start-up launched by a student of his that became an embodiment of the failures of start-up culture. According to one student, “A vote of approval from [Mehran] means a lot to other people who wouldn’t be willing to give you money or invest in you or take you seriously.”

Don Knuth

A legend in computer science who’s often called the “Yoda of Silicon Valley” and the author of the ongoing book project The Art of Computer Programming, Knuth has won basically every accolade in the field, including the Turing Award. If you’re a real CS academic nerd and think you know your stuff, Knuth gives a cash reward of $2.56 (one hexadecimal dollar) to anyone who finds a mistake in one of his books. “People talked about getting one of those checks as if it was computer science’s Nobel Prize,” webcomic artist Randall Munroe said.

Tina Seelig

Seelig wears many hats across the university. As a longtime shepherd of elite tech-management training programs like the Mayfield Fellowship, Seelig may have a bigger network in the Valley than just about anyone at Stanford.

No. 8: Maybe they’ll even let you TA.

Teaching assistants for CS courses make up an important network that feeds into Facebook, Google, and other big Valley companies: “It’s a smallish number of people, several dozen, all of whom know each other and are quite tight-knit because they have to work really hard together,” said one student. While TA-ing 106A and 106B might be slightly easier (since they’re introductory courses), you’ll have a better shot at landing one of the CS TA spots if you shoot for more advanced courses, where “the supply-demand ratio is much more favorable for applicants,” said another. On the other hand, if you already know enough to TA for CS 221/229 (AI/Machine Learning), “Tesla or Waymo or someone would come knocking pretty quickly.”

Being a research assistant can pay off too: “Somebody I know who’s starting a company worked as a research assistant. A lot of the professors at Stanford are angel investors in start-ups, so they will give checks to student companies pretty regularly and will advise you on those companies. Someone I know was at a research lab of one professor, and that person helped refer them to all these different networks and other ecosystems of people who might be helpful.”

No. 9: These classes are practically job fairs.

CS 147

Introduction to Human-Computer Interaction Design

Professor James Landay throws a project fair “where real-life people take a look at students’ shitty HCI projects.” One “sexy” recent project was Munch, “a unique platform offering instant, location-based dining promotions so consumers can find reasonably priced eating options and restaurants can moderate demand and control excess food supplies”—that is, an app where you can buy surplus food (a “sexy area of focus,” according to one student).

CS 221*

Artificial Intelligence: Principles and Techniques

The final-project session “is a direct means to cash out,” says Jonathan Yu, class of ’17. “Literally, like 3,000 people from industry, I think, went to the last one … One of my friends did a project using neural nets to seamlessly edit the selfie stick out of selfies. It was partially functional but clearly unfinished. And either Tencent or Baidu came in and offered to pay them $5 million to immediately acquire the technology and work with them. On the spot.”

*For the purposes of making billions, CS 229 is practically the same thing.

And this club literally is one.

BASES (Business Association of Stanford Entrepreneurial Students)

BASES is not a class but one of the highest-profile clubs on campus. Among other things, it hosts chats with entrepreneurs, runs the Startup Career Fair with the official campus career center, staffs teaching assistants for a popular guest-lecture series, and runs the annual Startup Challenge competition with a total of $100,000 in prize money. BASES is so well known that investors from all over the world will reach out to the club co-president, scouting for contacts.

Past successes include: Voltage Security (competed in 2002, acquired by HP in 2015), D.light (competed in 2007, currently has $100 million in annual revenue), Audacy Corporation (competed in 2015, now boasts contracts worth over $100 million), Boosted (competed in 2013, recently raised $60 million), and Eden Technology Services (competed in 2015, has raised over $15 million since).

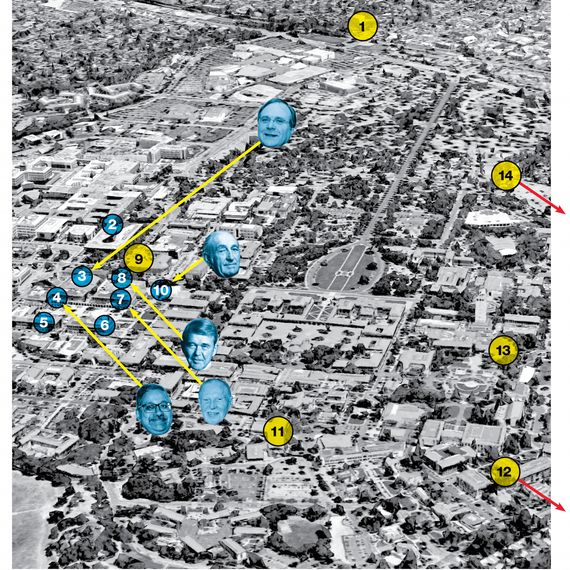

No. 10: Learn this money map.

1. Pear VC: A venture-capital firm located right off campus that likes to work with Stanford students — so much so that sometimes “people think they’re Stanford affiliated, and they’re totally not.”

2. James M. Clark Center

3. Paul G. Allen Building

4. Shriram Center for Bioengineering and Chemical Engineering

5. Yang and Yamazaki Environment and Energy (Y2E2) Building

6. Jen-Hsun Huang Engineering Center

7. Spilker Engineering & Applied Sciences Building

8. David Packard Electrical Engineering Building

9. Gates Computer Science Building: You may not even have to update your résumé to let recruiters know you’ve completed a class: Both Oracle and Palantir have been known to hand out cookies and refreshments from booths set up right outside classrooms where CS students are taking finals.

10. William R. Hewlett Teaching Center

11. Tresidder Memorial Union: Scope out computer-science events at Tresidder and you might be able to find eager VCs in the back row, looking for the next great founder.

12. StartX: A nonprofit, “not an accelerator,” located right off campus that often helps advise student start-ups. It doesn’t take equity and got rave reviews from founders we spoke to, especially for its free legal advice, training in fund-raising, and founder network.

13. Coupa Café: VCs are a fixture at the Coupa Café outside Green Library.

14. The Graduate School of Business: Needless to say, the GSB is well stocked with venture capitalists, investors, and entrepreneurs, checkbooks in hand—one way for undergraduates to take advantage is to find a B-school student in a team-based entrepreneurship class and offer to join the team.

No. 11: And if you can’t find them, find their “lookouts.”

Venture-capital firms like Sequoia and Founders Fund employ Stanford students to find other students who might be making the next Instagram in their dorm room. Here’s one former Stanford campus ambassador for Sequoia on how he got the job and how it worked:

How do people generally become student ambassadors for Sequoia?

It’s both cold calls and referrals from current ambassadors.

What does being an ambassador entail?

I always had my ears open to meeting interesting people on campus, and then, once a year, did a campus landscape, so just reporting on what things I was involved in and if there was anything interesting going on there. One time, I helped set up an event, bringing in one of the partners from Sequoia to speak at Stanford.

Did they pay you for the work?

No.

You did it for the network opportunities?

Being part of this community is super-helpful for me.

No. 12: Try to land one of these coveted internships.

Palantir

“Palantir, for a while, was actually above the big companies here. If you did a Palantir engineering internship, you were guaranteed a job anywhere else.”

The Elon Empire

“Tesla was the only actual mechanical-engineering firm other than Apple that let you live in the Bay Area and paid a decent salary, so everyone wanted to go work there. And then you had SpaceX, and they build rockets and they’re not a weird defense contractor.”

Google

“For product managers, the desirable one is the Google associate-product-manager internship or the new grad program.”

… But Not Amazon

“I was specifically advised to never work for Amazon. I was told it will make your life hell, they treat everyone really poorly, it’s a toxic culture.”

No. 13: And don’t sleep on non-tech extracurriculars.

(Also — just don’t sleep.)

Ballroom Dancing

Some of the best networking opportunities come from less obvious clubs. “When there’s a sufficient number of tech-oriented people in basically any Stanford organization, it can become a self-reinforcing pipeline by accident,” says Jonathon Yu, class of ’18. Take the Viennese Ball, for example. There is nothing special about a ballroom-dance group in particular that guarantees entry to tech, and yet: “The generation before me, a very large percentage of people went to work for Facebook, and this is before Facebook went public, because some previous members of the [dance] group had gone to work at Facebook, so they offered referrals … [The ball] just helps you make sure that you’re not going to get ignored when you cold-apply. One group of people from the dance is this subset of five or six people who now all work on the self-driving car at Tesla, which, considering that’s probably only 40 or 50 people, is a large subset of their AI team.”

Stanford Review

The Stanford Review, co-founded in 1987 to provide a contrarian and mostly right-wing perspective, is still tied to its co-founder Peter Thiel, who regularly hires Review editors to venture-capital firms and companies he co-founded as well as nonprofits he funds. Three co-founders of Palantir — Thiel, Joe Lonsdale, and Stephen Cohen — were editors-in-chief of the Review, and overall, about 40 percent of Review editors-in-chief over the past 30 years have interned or worked at a Thiel- or Lonsdale-affiliated institution.

One way to signal your affiliation with the Review — and to get some attention from Thiel — might be to carry around a René Girard book: There’s a funny (one might say mimetic) pattern of Stanford Review editors being fans of the late French philosopher, who was a Stanford professor and an inspiration to Thiel.

Dressage

Okay, so maybe you don’t have a killer app or a head for numbers … but maybe you have a horse? Two of the tech industry’s most prominent scions, current student Eve Jobs and recent grad Jennifer Gates, are both equestrians (the Gates family also donated a horse). Brush up on your dressage and maybe you have a chance at entering the upper echelons of Silicon Valley without ever needing to make a pitch deck.

No. 14: Or forget all this and just drop out.

“I think the third week of fall quarter, I was living in Uj, and there was some kid in Roble who dropped out to go work on a start-up full time. He was like, ‘You know, this was fun, I’m glad I tried the whole college thing, but I have other shit to do. I have better things to do.’ ” —Jackson Beard, class of ’17

“If you’re still a student, all the investors want you to drop out.” —Human-biology major, class of ’16

“Someone I know dropped out of Stanford to work on this competitive cloud-based replacement for Microsoft Excel, and the whole thing kind of imploded. Apparently, he was a jerk and they got rid of him, and now I think he’s an Instagram influencer working on cocktails. That’s his big thing now.” —Mechanical-engineering major, class of ’16

*This article appears in the September 2, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!