At 7 a.m., Donice Ford-Benson is working in the rain on the unfinished 17th floor of 550 Vanderbilt. She’s checking a drain system but pauses for a moment because, even in the downpour, she can’t resist taking in the panorama of Downtown Brooklyn. The spot where she stands will soon be a balcony and belong to whoever buys the condo and the views. According to the developer’s website, the building will be “Setting the Standard for Brooklyn Living.” Construction is almost complete, and when it is, Ford-Benson will then be out of work. She’s been a union plumber for 17 years; it’s a familiar cycle of episodic work, one that has driven her family in and out of homelessness. Currently, her daily commute is between the new standard of living on Vanderbilt Avenue and the Help 1 shelter in East New York.

Over the last several months, I met a lot of working people like Ford-Benson while interviewing homeless New Yorkers. They cut hair, serve food, care for the elderly, and run after-school programs. They’re not an anomaly: 71 percent of the shelter population is made up of families, a third of whom have a head of household who is working. “The new working poor are homeless,” says Christine Quinn, the former City Council Speaker who now serves as chief executive for Win, a shelter provider for women and families. “A lot of them work for the city or not-for-profits. I can’t tell you I don’t have a Win employee living in a shelter somewhere.”

While the city’s tabloids spotlight mental health and drug dependency as contributing causes of homelessness — and, indeed, they are — the biggest factor, particularly for the working poor, is a familiar New York story: stagnant wages and soaring rents. Between 2000 and 2014, the median New York City rent increased 19 percent while household income decreased by 6.3 percent. In that same period, the city’s homeless population more than doubled from 22,972 to 51,470. There are now around 60,000 people in the city’s shelter system, an all-time peak.

Eight New Yorkers explain why it’s so hard to stop being homeless.

The assistant teacher fighting for basic necessities.

Abena Walker,

36

Resident, with her two daughters, ages 8 and 16, of Help 1 in East New York. Homeless since: September 2015.

When I was younger, I thought I was smart and tried to venture out on my own, and I realized that I stepped out a little too far. My mom has Section 8. When I left, I took myself off the lease, so I was no longer part of the household composition registered with the city. I had to come in as if I was new in the system. So I was stuck. Staying with people wasn’t working. So I had to find somewhere to go.

When I walked into PATH the first day, there was a fistfight between two people, with their children standing right there. You know what’s demoralizing? The contract they make us sign. You done sold your soul. You gotta have investigators come out and dig through to make sure that you ain’t lying to them. Then, you have to go through case managers, health things. I’ve taken about three or four TB tests. I’m surprised I don’t have it by now. You have to go through psychiatric evaluations. Does that sound like fun to you?

September 1, 2015, they sent me to the Ramada on North Gannon [in Staten Island]. It was near a bus stop that never worked, two stores, another bus stop, and a library. The first question I asked was “If I wanted to leave, how do I get out?” A guy at the hotel said, “There’s a bus there, and if you want you can walk.” He didn’t say it was three and a half hours just to get to St. George to get on the boat to leave. I said, “I need to get out of here.”

The guy said, “Why?”

“Somebody can get killed here, and nobody would know anything until I was clean into Harlem.” I must have felt something because not long after, that’s just what happened. I was reading that thinking, Wow, I was joking — I didn’t think it was actually going to happen.

That was the hotel from hell. You can’t use the common areas. They let us know that there were people paying to be there, and being that we weren’t, if we were to use the microwave to heat up food, to make sure there was no one in the kitchen. My question for the guy from DHS was, if they’re getting the same money from DHS for us to be there as these other people who are paying out of their pockets, I don’t see what the problem is. There’s a stigma that comes attached to us.

I was there for about a month. I couldn’t deal, so we had to go back to PATH and start over. I was told I was going to Manhattan and they put us in Brooklyn. It’s like, Okay, the number came up, Brooklyn, here we come. What can I tell them? I just rocked with it. So I live in East New York.

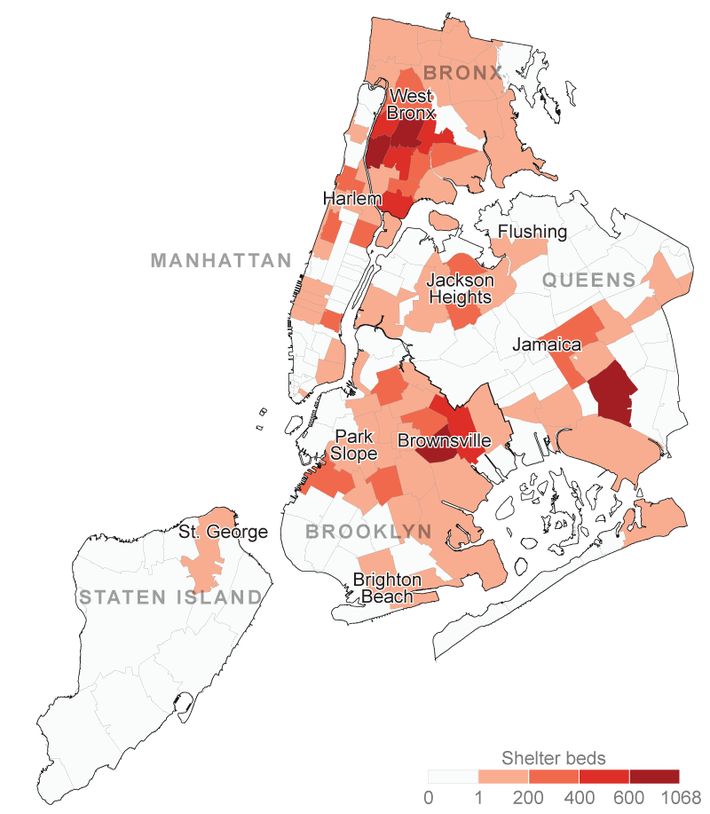

Total shelter rooms by ZIP code for families with children

I have two daughters. My little one goes to Neighborhood School. The older one, she goes to Mather High School. She does ROTC there. She said she wanted to be an EMT, but then she said that blood made her squeamish, so she decided that she wanted to be a lawyer. I told her that works. As long as she’s not a cop, I’m good. I work in Harlem with the Y on 120th. I work with children. They’ve labeled me an assistant teacher, so I have to do lesson plans and set up programs so that they are not just bored for three hours after school.

During the week, we have to get up if we want to be on time and comfortable, at about 6 a.m. Tuesday is a very special day for me, because I have to drop the two of them to school and then turn back around, come back into Brooklyn to go sit with my case manager, then go to Harlem. Meeting with him is pretty much like a therapy session, because there’s not much else he can do for me. We’ve exhausted every avenue. But I do give him credit because he tries. Basically what happens is we go in, I complain, I tell him what’s not being done. And he’ll do whatever he can to get what we need. He’ll make sure I still have a checking account and a savings account. He’ll go over an Independent Living Plan. The ILP is basically a bunch of things they feel are important to have you leave the system — you have to make sure your children in school; you have a job, which I already do; you’re putting a percentage of your money in a savings account.

[At the shelter], me and my kids have a two-bedroom. My window is directly across from my bed and there is no insulation, so I had to get garbage bags and close up the window so that the outside stays outside and the inside stays inside. We have a full kitchen, but it’s in the living room. The vents are dirty. We’re always sick. And mind you, I bought my own toilet seat. I have currently, to this date, spent about maybe $150 on just repairs, because, I’m sorry, I have children in there, and I know what a rat bite is like, and it’s not a good feeling. I’m a parent first, inmate second. I will not do anything to jeopardize my children.

Curfew is supposed to be 10 p.m., but if you work, they extend it to 3 a.m. We can’t have guests. That’s not to say that you can’t get in. You just wait for the lobby to get very crowded, and then you just walk on by. They won’t even notice. By security’s own admittance: We had a guy get in with a gun, and they said that they weren’t going to risk their lives to go stop him. We cannot have scooters, bikes, roller blades, or skates for our children. We’re allowed to have floor toys. And we can’t have full-length mirrors. The assistant director said it was a safety issue, that if the mirror had fallen and my child got hurt, that would have been a safety concern. I said, “Right, so if I happen to get up and go to the bathroom and happen to see a mouse and it decides to bite my foot, that’s not an issue for you?”

“Oh, I can’t control mice, but I can control your mirror.”

Now, let me show you some of the lovely conditions that I was introduced to with my children. [She pulls out her cell phone.] That’s where mice were coming from, and they were gymnasts because they managed to get over the traps. Yes, they jump. Now, this is the hole where they were coming in and out. I think I fixed it better than they did. That would be plaster and, I think, Spackle from Dollar Tree. This is what prompted me to do it — rat droppings on my stove. See, this is why they don’t like me. I don’t have to say anything, I just show you a picture.

Now, the contract I signed when I sold my soul to DHS was I was entitled to safe and sanitary. My unit definitely wasn’t safe and, as you saw for yourself, definitely was not sanitary. I know one lady at the DHS complaint office by first name. At this point it’s like, “What can we help you with today?”

See, when I came for orientation, they misunderstood me, because they ask us who our role models are and I said, “Well, unfortunately, all of mine are either dead, in jail, or fleeing prosecution.” And the woman looked at me and said, “Well, you need a better class of people.” I said, “Exactly how did you understand what I said?” She said, “Well, I don’t think I understand fully.” I said, “I know you don’t, because there are no better role models than Malcolm X, Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis, and Assata Shakur.” I live by the philosophy of Malcolm X: You may not want to give it to me, but I’ll get it by any means necessary. I will do it with a smile on my face.

I save money. I’m still sitting on tax money. I know if my paycheck is a week away and my child needs something, I can go in there and pull it out and get what I need to get. Listen, I’m the type where you ain’t gotta teach me how to hustle. Don’t nobody give me anything.

I’ve heard the terminology “easy.” People would tell me that it’s “easy,” that we “want” to be there. That is the biggest misconception. Come experience my life. I guarantee in a week you’ll want to go home. I have to fight for basic necessities, how is that easy? To be displaced, and at any given time, somebody can decide they’re sick of seeing my face, and you have to pack up everything you own and go. If you get too many FTCs, [“failure to comply”] you’re going right back to PATH. To be in the shelter you have to have an active case. If you close that active case by missing an appointment, you get FTC’ed. If you don’t sign the logbook before curfew, that’s an FTC. If you make repairs in your own apartment, that’s an FTC. FTC is: We have the power to throw you out. That’s pretty much what they use to keep people in line around here. It’s their form of retaliation. Sometimes it feels like anything you do can be an FTC. We can get FTC’ed for breathing the wrong way.

Just to be treated as a human is a pain in the ass. Picture that every day except for when you go to work, you don’t hear your name, you’re a number. That’s the common problem with this whole system is that we’re not looked at as human beings. Since I’ve been in this system, the only time I hear my name is when I see my case manager. Otherwise, I’m a 12-digit number. I’m not a person. I’m an ID. This is why I say it’s like jail, because when you go to jail, you are not a human anymore. It kind of reminds me of Full Metal Jacket: “Name, rank, serial number.” My name? Irrelevant. My rank? It’s still irrelevant. But my serial number, they make sure that they get that.

The couple moving from couch to couch.

Abree Bolden, 37, & Lyndsey Vena, 36

Currently participating in a methadone program for heroin addiction. Homeless since: Sometime last year.Bolden: I had just got home from prison, doing five years. I’ve been out a year now. When I first got out, those first 90 days I had my children. I have four children. One of my children is incarcerated in Arizona. But I woke up with three of my children in the bed with me every day. After three months, it didn’t work out, so I had to go out on my own. My kids live with my mother. I know eventually I’ll be able to get them back. I went to a shelter, but I didn’t feel safe there. Every time you look up, someone is stealing something.

Vena: You get into these places and the mixture of people, it just doesn’t vibe. There are people with mental issues that just need a higher level of care.

Bolden: I seen a man come back to the shelter after open-heart surgery, and they wouldn’t let him bed rest. They make him go out at nine o’clock in the morning with everyone else and come back at three o’clock. You can find anything and everything in the system. I saw a female staff member who was messing around with a guy — a client, whatever you’re supposed to call him — and when it went sour, she kicked him out and sent him to one of the worst shelters in New York.

When you have rage and outbursts, it can get crazy in there. I’ve seen it with the staff members, they try to take down one guy, and it takes like ten of them. Once they get him, they own him. I seen them beat a mental-health patient up. But when you’re in the shelter system, they don’t really care. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of “deliberate indifference,” but they’re deliberately not doing what they’re supposed to be doing in some of these shelters. You got some good people working in the system. You can tell who they are. They been there for four or five years. It ain’t about a paycheck. They smiling. They might help stop someone from jumping off a bridge and at least make it to tomorrow.

I was going through a program and I asked this lady, “You know if anybody’s renting a room out?” She got me a one-bedroom, $250 a month. I was there for two months. I was so at peace. But the person who owned the apartment stole some items from me and sold them. I lost maybe 19 pairs of clippers. I’m a barber and an electrician. I cut hair, so that’s been holding us down. I’m very talented and gifted with that. I travel with my barber tools wherever I go. As long as there is an outlet, I got you. I got to make ends meet by some means, somehow.

Right now I’m struggling to find a place to live. I can’t see myself going back into one of these shelters.

Vena: It makes it really difficult to secure a job if you don’t know where you’re going to be sleeping. How are we going to get up and shower and go to work like normal, everyday people when we don’t have a headquarters?

Bolden: I’ll work anywhere. I’ll scrub floors right now just to get steady income. I stop in any store: “Are you guys hiring? Do you need help?”

Vena: Yeah, any store we’re in, we’re always questioning if they’re hiring. If he sees people with painter’s pants on, he’ll ask, “Oh, are you guys painting houses?” Home improvement — anything — 95 percent of the time that doesn’t pan out. Both of us have real work histories; we’ve been successful in life. I used to be a behavioral counselor, case management. I have a bachelor’s degree in sociology with a minor in women’s studies.

Bolden: I have my associate degree in business management. And I was in Arizona Western College for basic engineering when I was incarcerated.

Vena: Needless to say, we’re both highly educated people who have fallen on hard times. It’s a vicious cycle because you can’t get a job because you don’t have anywhere to live, and you don’t have anywhere to live because you can’t get a job. If we had a voucher to try to get some kind of housing, that would be a step in the right direction, but you get so many stories about how to do it and nothing pans out. It’s like pinball, and someone just keeps pushing the button: “Bounce, bitch, bounce!”

Bolden: Right now, we’re staying here and there, renting out a couch or something like that. I have friends. We’re always trying to make sure we got a warm meal in our stomach wherever we’re at. Because we don’t know where we’re going to be at that night to eat. Last night we found a reasonable bed; we was warm.

Vena: We have a place for tonight. In our travels, we came across someone who is willing to take $20 a day from us. But then there’s the part of finding the damn $20, which sometimes causes you to do things you don’t necessarily want to do. You got to sell something you don’t want to sell, you know what I mean? By any means necessary. I will do my best to make sure he’s okay and he does his best to make sure I’m okay. Whatever it is, we’ll make it work.

It’s pretty damn cold outside. We’re lucky that we have one another. When you’re with somebody, it’s kind of like you have a teammate. On the other hand, it makes it more difficult because now you’re worried about two people instead of one person. But we try to be grateful every day for what we find that day. Every day we work on today. There is no working on tomorrow. We have plans for our future. We want to grow old together and have babies and do all these things, but it’s like, how can you look past eight o’clock tonight if you don’t know where the hell you’re sleeping?

Bolden: It can be harder when you got someone with you. When you’re alone, you can shake and move. When you’re with somebody, you have to be mindful. And I’m grateful for her. I’m blessed to have her in my life.

Vena: Ditto.

Bolden: I just have to get better at some things. I have to be a better man. I want to get better at communication — and be more humble. I got a lot of energy, sometimes not the best energy but —

Vena: You have the tendency to make decisions on a rash, quick response and not think about them. And that can be detrimental — life and death.

Bolden: You heard her? That one second can be life and death.

Vena: Especially living out here the way that we are, you don’t know who you are dealing with. It could be anybody and they can tell you, “Sure, come over to my house and I’ll put you up for the night.” And then they end up being a serial murderer.

Bolden: You’ll be in their deep freezer.

Vena: I’ve actually had an incident. I rented a room in a nice house on the border of Long Island and Queens, and I was violated by one of the roommates’ boyfriends.

Bolden: He got violated afterward.

Vena: He sure did.

Bolden: We didn’t file complaints. I’m a street dude, I’m not going to lie to you. I seen him and put him in the bathroom for about an hour. I let him know. He probably won’t ever touch another woman like that.

The home health aide who’s No. 25,000 on a housing waiting list.

Nezette Tyson,

36Resident, with her husband; son, age 11; and daughter, age 2, of Help 1 in East New York. Homeless since: September 2013.

The first time we attempted to enter the shelter was in 2005, after my son was born. The house that we were in, on Prospect Avenue, was being foreclosed upon. I didn’t have my son’s birth certificate, and they said we needed to wait for that to come before they would do our intake. We stayed at my husband’s mother’s house for several weeks until the birth certificate came. We went back to PATH, and they put us at a temporary shelter in Manhattan while they did the investigation. They spoke to his mother. She confirmed that we had stayed there while we were waiting for the birth certificate and they immediately denied us and told us we had somewhere to stay.

We ended up living with my mother in Peekskill. But after a while, her house ended up getting foreclosed upon. Then we moved to Queens and stayed with some friends there. But then we were robbed by some of their friends and ended up back at PATH in August of 2008.

My son was 3 by then. They placed us in a temporary shelter while they did the investigation. They always tell you it’s ten days to get placement. Some people get placed the same day; some people get placed in a hotel and they have to keep going back to PATH every day until they get a placement. I’ve had friends stay in hotels for two to three months. In September, they told us that they would continue to deny us because his mother still lived at the same address. So we got turned away for the same reason.

After that, a friend of mine said, “I live in a rooming house out here in Brooklyn; come stay with me for a little while. We’ll manage it.” We did good for about six years. Then we saw somebody outside taking pictures of the building. I started searching online, and I found out that the building was on short sale. Next thing we know, the landlord gave us a letter saying that we had to leave. We fought with that man in court for two years, but we ended up getting evicted.

Then we went back to PATH. Now we live at 515 Blake. It’s called Help 1. I was four months pregnant when we arrived. My daughter was born there. She’ll be 3 in April.

When you’re in a shelter, there’s all these different departments and all these different people that are passing your paperwork from one person to another. It’s very easy to get lost. You’re a number. You’re a monetary amount in a budget for them to keep this thing going. The unfortunate truth is that there is more money in us being homeless than there is in us being productive members of society. Help 1 gets paid $2,000 a month for people to live in a room that’s, like, 12 by 12.

I see my caseworker, Mr. King, every week. He is always consistent. We have housing specialists that leave on a regular basis. It’s a revolving door there. Not that the housing specialists do any work. As I understand it, a housing specialist is someone who will assist you in locating permanent housing — accessing brokers or landlords that take programs. The problem is I’m not getting any of that. We qualify for a program called Tenant-Based Rental Assistance, TBRA. It’s basically a rent voucher if we find an apartment. I got that by myself. It took seven or eight months for me to get it. Now the issue that we’re having is the landlords that know about that particular program are not willing to run the risk of taking another program. It’s federally funded, but the Advantage program from a few years ago was also funded and Bloomberg shut the program down.

I saw one apartment through a housing specialist in September of last year. I’ve seen three apartments since the end of December. Me, on my own. I have a folder on my phone with a whole bunch of different apps — Trulia, HotPads, Naked Apartments. Between August and December, I was sending in requests for apartments anywhere. I wasn’t getting any responses back. I say, plain out: “I have a program, my husband is working, it’s a family of two with two children.” We’re not getting any responses back. I have folders full of applications that I’ve put in on Housing Connect, the website where you fill out applications for low-income houses. They tell you what your number is on the list. On some of them, I’m like 25,000.

In November they called me in for a case conference. “Oh, you’re being noncompliant because you’re not looking for apartments.” I pulled my folder out of my bag. I said, “This is everything I’ve done since I’ve been here. There were four pages, 50 listings per page. Now that I’ve showed you mine, show me yours. What do you have for me?” They didn’t have anything.

My caseworker, I saw him two days later, and he just started laughing. He was like, “I told them to leave you alone. They don’t know that you are the paperwork master!” If they ask for anything, I have it. I scan everything because everything in this process is paperwork. When I sign the roster at night, I take pictures of the roster. I’m very meticulous and, to be quite honest, paranoid, because at any given time, they can say, “You violated … you have to leave.”

I had a neighbor two doors down from me. She said, “I don’t want the exterminator. Whatever they’re spraying is bringing the roaches in. I have bugs falling on my kids, so I’m handling it on my own. I’m laying down the gel. I got it.” They waited for her to walk down the stairs, they pulled out the keys, opened her door, let the exterminators in. She comes back and starts yelling at them. The security guard goes over and said, “She threatened us. We don’t feel safe.” They kicked her and her family out on a Sunday. They didn’t even give her a 24-hour notice.

It’s very easy for those kinds of things to happen. But I will never say anything about the security guards because I know the things they go through, too. One of those guys, one of the clients chased him down with a knife. And one time there was a lady that had been gone for three days and she was upset that her supervisor told her she had to go back to PATH, so she and her daughters jumped the supervisor. So there are situations where they deal with violent people, angry people who come into these places.

They had a rule that after 4 p.m., they would not sign us in without our children. My husband came in from work one day on a Sunday, maybe 5 p.m. I was in Jersey visiting my mom. They wouldn’t let him in. He had to wait for us to come back from Jersey so that he could get into the complex. I asked DHS, “Why is that?”

“You’re a family unit. You’re supposed to go together.”

I said, “But if you’re promoting a household to have both adults working, how often is it going to be that both adults are available at the exact same time and coming in with their children? That’s unrealistic.”

My husband landed a job at Best Buy. He had a lot of disagreements with one of the managers there. One of the disagreements pertained to the facility that we’re in now. He would tell his manager, “I have a meeting, I have to come in a little bit late.” They wouldn’t accommodate him. He lost his job last year. We both felt strongly that the fact that we were in a shelter was an issue for them. He just started working security. I started work for a family friend at the beginning of February as a home health aide. I’m going to get a security license as backup because days that she’s in the hospital or God forbid she passes, I won’t get paid.

I’m trying to make us financially stable. I cleaned up my credit, I cleaned up my husband’s credit. I got my student loans out of default and was able to put it into forbearance, so now I’m able to get my stuff together so I can go back to school. I’m trying to go back to school in September. I’ve been reading up on the stock market. I have a stock-trainer app, so I’ve been looking into that. I’ve been looking into investing.

The former postal worker who knows which trains to sleep on.

Alan Negron,

56 Resident of the New York City Rescue Mission in Chinatown. Homeless since: 2013 (most recently).I’m from right here — this neighborhood [Gowanus], all my life. I spent the first ten or 11 years on Union Street, on Garfield Place. That was the best part of my childhood — stickball, cocolevio. And then, for like 32 years, we lived on Butler Street. In my father’s house, there were nine of us. My parents come from Puerto Rico. I remember when the Puerto Ricans and the Italians were fighting on Fifth Avenue. I remember when Fifth Avenue was mostly abandoned from, let’s say, Barclays to Flatbush, all of Fifth Avenue, all of the buildings were abandoned.

I used to work for the post office, as a clerk. Fourteen years. And before that, I did construction. I still do odds and ends like side jobs: a sink, a faucet, a light fixture. That’s what I do. I make my living and get my food stamps. I’m like a jack of all trades and master of none. My ex-wife, she drives a city bus.

To be honest, it was the drugs and the alcohol and fighting with my wife and carrying on and losing my job, losing my wife, father died, mother died, and at that time, I was just gone. Mostly cocaine and alcohol.

I still drink. I never get piss-faced. Well, no, no, I say “never,” but 98 percent of the time I don’t drink to do that. I drink just to drink. I haven’t had no cocaine in over 20 years now. I don’t know if it was that I couldn’t afford it, or what happened with the wife and everything else. We never got divorced. When we left each other — I’ll tell you the truth: She left me. In ’96. I wasn’t going to leave my children. I have three. They’re grown. They’ve got their lives to live now.

I was living on the streets. I was sleeping in the park right here on Douglass and Third Avenue. Also, do you know Saint Augustine on Sterling Place and Sixth Avenue? Me and a couple of my friends, we stayed there for two or three months in the summer.

About four years ago, I had double pneumonia. It started in the wintertime, but it was in the early spring and I’d see everybody walking around with T-shirts, and I’ve got a coat on because I’m freezing. I had no idea why until my brother told me, “You better go to the hospital.” Then I started getting weak. The last thing I remember is talking to one of the lady EMT workers. Then, after that, I got up two weeks later. They had put me in a medically induced coma. And I had to stay another three weeks because I had to get my legs working again. I lived with my sister for a while after that.

Later, I moved over here by Sackett, by the Speedway station. I set up shop there. I had like a little tent. It wasn’t an actual tent. I got two chairs and a solid door and that became my bed. I found a mattress that I picked up off the street and put it on top of there, found some blankets, and there I slept. I was able to keep it there for damn near eight months maybe.

I didn’t want to go into the shelters because I’ve known people who been in shelters. They go, and they’re back on the street four or five days later because there’s fighting, there’s thievery, there’s people trying to hurt you for no reason whatsoever. You can’t take off your shoes at night because they’re gone in the morning.

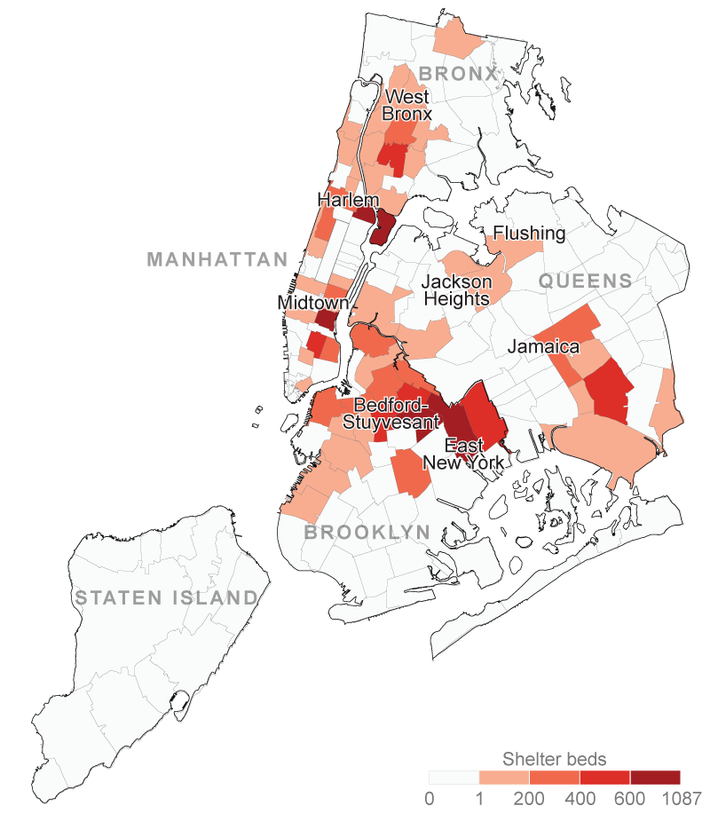

Total shelter beds by ZIP code for single adults

I don’t care what homeless person you ask, the No. 1 reason that they don’t go to those shelters is because of the danger in it. You’re safer sleeping in the street than you are if you go to a place like Bedford. You’re a hell of a whole lot safer because you choose where you sleep. In this neighborhood, ain’t nobody gonna bother you. They see you, and they keep walking, but you go to a shelter and somebody thinks you’re easy picking or whatever, then there’s a fight.

I thought, Why experience it myself? What if I go to sleep and it’s wintertime out and I get up in the morning and my boots are gone, and then they’re going to tell me I have to leave. Then what? I’m walking around outside barefooted in the snow. Better I keep my shoes than to find out for myself, trust me.

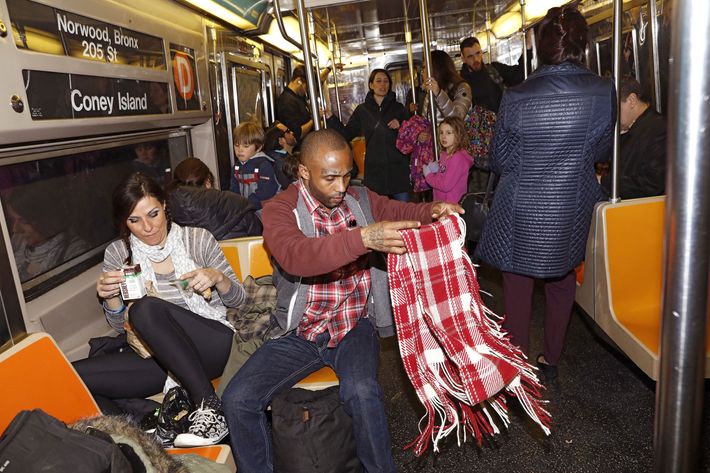

There are places to go. You don’t literally stay outside in the wintertime. When it was cold, I’d stay on the trains. Find a train like the E train or the R train that stays inside. Like the D train goes to Coney Island. It goes outside and the conductors, they leave those doors open, as cold as it is; they know you’re there.

A lot of the conductors, they feel that they’re not safe here with the homeless, but the majority of the homeless people, they’re not bad people. The people that they’re not dressed right or they smell to high heaven — I smell it, too. I don’t knock them, but those are the people that have illnesses. You see? But you can’t put everybody in the same boat. Those are the people they see. They don’t see the homeless people. Some homeless people, when you look at them, you would never believe [they’re homeless].

There are places to take showers. Right here on St. Johns and Seventh Avenue, the church on the corner, you go on Saturdays, you take your shower, they’ve got clothes for you; socks, shoes. Going to a place like CHiPS, you will never find a better place, whether you’re homeless or not. A lot of people that come here, they’re not homeless. Like older folks who want to socialize with other people, and CHiPS gives them that opportunity. I come here every day.

It was last year, December 22, when Breaking Ground came and got me. The first time they approached me, I told them I didn’t want to go. I told them, “No, no, no, no! I’m good here.” But I had to do something, right? They talked to me and had me fill out a form and then have someone that was employed and wasn’t homeless to vouch that they saw me sleeping in the street for so long.

I moved into a shelter called Camba. It’s here in Brooklyn on Atlantic Avenue, but it isn’t a shelter like people perceive it to be. If the psychologist thinks that there’s something wrong with you, you can’t stay there. They’ll refer you to another shelter, so everybody is basically in their right mind, you see. You go, you eat three times a day. One little thing that you do that shows aggression, you’re out. There’s no fighting whatsoever. If you steal something and they look on the camera, because they’ve got cameras all over the place — even when you’re sleeping — and if you’re caught doing it, you’re out. They got showers there, they got a laundry room where you can wash your clothes. They got a bank where you can save your money if you wish to. That’s part of the rules: They want you to save money.

I go to Workforce maybe two times a week. It’s a place to find work. Like the unemployment office. It’s the same thing, computers and everything else. I want to try to look for work. I don’t mind mopping floors. Shit, I don’t mind cleaning the toilet bowls, I don’t care, but those jobs are already taken.

After I leave CHiPS, I go visit my sister. I stay with her a couple of hours. Then I go to Target because that’s where my friends are. In the cafeteria. That’s where homeless folk are. Most of them are of sound mind. You’ll know the ones that you don’t want to deal with, but we hang out there. I stay there until about 7 p.m., and I walk back so that I can make it to the shelter before curfew. Sometimes I’ve got money to get on the train, so I stay there until 7:30 p.m.

People think that people are homeless because they choose to be. I’m not saying it’s not my fault, but I didn’t choose to be this way. Everybody’s got their different reasons why they are the way they are, but nobody chooses to be homeless.

The hairdresser who can’t save enough to get out.

Bertha Martinez,

24 Resident, with her fiancé and son, 3, of a Win shelter in Flatbush. Homeless since: January 2016.I grew up in Manhattan — East Harlem, El Barrio, Johnson Projects. We’ve been living in there since I was 6. My mom still stays there. Forever I’ve lived with my mom or I’ve lived with my sister. We went through a lot with our families. You could feel the tension in the room whenever we all got together, and I felt like the problem was us, the problem was being in people’s space. It was just too much. So, I was like, You know what? Let’s just go. Everybody is saying we can’t stay. We’re feeling funny vibes, and you could tell we overstayed our welcome. It was time for us to go.

It was literally overnight. I just decided after work, I’m going to go get my son and I’m just going to go sit at PATH. January 6, it makes a year that I’ve been a part of the shelter system. The one that I’m in right now, it’s not the worst. This is the second shelter I’ve been in. The first one was located in the Bronx, on Grand Concourse. It used to be a hotel. It was horrible. It was disgusting. I deal with roaches here, but it’s nothing like how it was over there. It was not a place for my son.

They logged me out of the system, so I had to go through the PATH system all over again. What happened was they said that my son wasn’t staying there with me, and they were right. I would avoid staying there as much as possible. Sometimes I would sign in and leave. I’m going to be honest, I’m a mom first. I can go through whatever, but my son is not going to go through that. He was literally getting bit by roaches. I would wake up and he’s moving and tussling, and I’ll put on the flashlight and there’s a roach crawling on him. Instead of me saying, “I’m leaving, I’m going back to PATH so they can place me in another shelter,” I just took him out. I guess they must have caught on to that. I came from work and my caseworker calls me and tells me that they logged me out. I didn’t 48, but they logged me out. They have a “48 rule” where you can’t stay out past two days or they’ll log you out of the system. I came into an empty room. I was so broke. I had spent my last $30 on food shopping. They threw away all of my food. They wouldn’t give me my money back. They wouldn’t do anything for me. It was a blessing in disguise because I ended up here, which is much, much better than where I originally was.

This is a Tier II shelter, where it’s like an apartment. Every apartment is a studio apartment; bathroom, kitchen, refrigerator, we just don’t have an oven. When I first got here, I felt like a foreigner. It’s really far from where I have to work. I actually work in Harlem. I’m a hairstylist. It takes me about two hours to get to Harlem and two hours back, so that’s four hours a day. I drop my son off at school at 8 a.m. I get to Harlem around 9:30 a.m. or 10 a.m. My first client is about 10 a.m. I have to leave by 4 p.m. to be able to get him from school on time. I pick him up from school, and then I’ll come here. The travel, it takes away from the money that I could be making. People say, “There are so many hair salons in Brooklyn, why don’t you just move to Brooklyn?” I keep the location in Harlem because that’s where I’ve been doing hair for a long time now. I’m here with my fiancé, my son’s father. He’s a full-time student, and he works as an actor. After school, he has work-study, so he works in school. He doesn’t get paid much. After work, he has basketball practice because he’s a part of his college basketball team, and he doesn’t get in until 11:30 p.m. or midnight depending on how the trains are running. We get passes because we work and we go to school, which gives us the ability to come in after curfew.

Sometimes I feel like, before I even came into the system, I was told a lot of stories. Some people, they say, “By six months, you’re going to get an apartment, don’t worry about it.” I know people in here that have been here for almost two years. We have a housing specialist now that I heard about recently. I guess the housing specialist is a person who helps us find housing, so that’s a good thing.

For the vouchers that they give us, a lot of the landlords won’t accept them. That’s another delay; the fact that we don’t get good enough programs to help us actually get out. It’s kind of like it’s pulling us in more than it’s trying to help us get out.

For whatever reason, I got denied cash assistance. Pretty much everything we have and everything we do is out of pocket. I feel like the system doesn’t help people who work. It’s like you’re meant to be lazy. You’re meant to be a bum. That’s the only way you can possibly get any help from them, is if you’re not doing anything to motivate yourself.

I have to save up enough money to go into my own apartment. They send us these notices that they want us to save at least $200 a month. How can I save? Everything that I’m working for is to maintain what I already have. I can’t save. There is no room to save. That’s the thing about being a New Yorker: We live paycheck to paycheck, period. Unless you’re a millionaire or billionaire, you live paycheck to paycheck.

I just don’t want to go through this no more. I want to cook a decent meal. I want to be able to come in when I want to come in. Sometimes I feel myself about to cross that line. I do cry sometimes. Me and my fiancé, it causes friction between us. All we keep asking is, “Why?” “Why are we going through this?” We’re great people. Where did we go wrong?

I look at my son and break down sometimes. He doesn’t know what’s going on, but he doesn’t deserve to be here. The longer it takes, the more you start to beat yourself up about the situation that you’re in. As positive as I can be, I do have my moments where I just want to throw a plate across the wall.

I’ve always tried to make the best of my situations, because I feel like a positive thought brings positive in your life. I’ve already braced myself for knowing that this is just temporary. I don’t get comfortable because I know this is not home. I am going to get my apartment eventually, but I have to figure out my master plan.

The union plumber who makes too much, and too little.

Donice Ford-Benson,

49 Resident with her husband and two of her sons of Help 1 in East New York. Homeless since: August 2013 (most recently).Because I’m in the union, sometimes I work, sometimes I don’t. I always get laid off and have to go back to the shelter. I’ve been in and out, in and out.

The first time was when my kids were little — 1992. That’s when they had EAU. The EAU was like PATH. There was an issue with people sleeping in the EAU for weeks waiting to be housed. We were there for two weeks, me and my three kids. We had to watch violence and a whole lot of stuff.

Eventually they sent me to a Red Cross shelter. I was there until 1997, when I got Section 8. I found an apartment with my Section 8 voucher. And then there was a fire. I was at work when they called me. My kids were in the house, but everyone was okay. I ended up finding another Section 8 apartment. I was there for about five years. At one point I had to keep calling the city on the landlord, because for over a year I didn’t have heat or hot water. Eventually the city came and shut down that building because of all the violations, so I had to leave. I ended up staying with a friend for a little bit. After that, I went to my mother’s house. I was there for a few years, but then finally my mother said, “You’re 40 years old. You need to find something else.”

In 2010, I went to path. They sent me to a shelter. It was me, my husband, and two of my sons. I wasn’t working at the time. But as soon as I got in there, I started working. So then they started rushing me out. We were there for a good two, three months. But you have to understand, even if you do get into an apartment you still have to buy so much. You have to have a bed. Remember, I didn’t have anything at all ’cause I’d lost everything in the fire.

When they made us leave, I found an apartment in Bushwick. I was working on the Freedom Tower, but I got laid off from that May 31, 2012. I was out of work for three years. I had depleted my whole 401K paying the landlord the rent until I couldn’t pay no more. And that’s how I ended up back in the shelter system.

New York used to be union. Now we’re seeing nonunion work taking over union. A while back, I finally said screw it and took on some nonunion painting. I was only making $10 an hour. And the guy who hired me knew I was a plumber, and he was trying to get me to fix some slop sink in the building. But I know my rights. I was doing that until the union called me back last year, July.

Right now I’m working on Vanderbilt and Atlantic. I’m making $67.71 an hour, but we’re almost at the top, so that means layoffs are coming. Next year, I can make zero. And then what? If I go to a real-estate office it’s like, “Okay, you have a union job. What happens when you lose your job?” But if I’m going to city housing, everything is “You make too much.” Me and my husband, we got found eligible for public housing at 600 Euclid. We went to go look at the apartment, and they start saying, “Can we see your pay stubs?” I give them my pay stubs. And they start saying she makes a certain amount. All of the sudden: “We can’t help you.” I’m not eligible. How am I not eligible?

At this point, I don’t know what to do. I’m so tired of hearing I’m not eligible. It’s getting depressing. It’s making me suicidal. I feel trapped. I haven’t seen a housing specialist in so long it’s ridiculous. Even when I do get a letter telling me about an appointment it says the meeting’s at 10 a.m. I’m not taking a day off work — I can’t do that. And they know that. And they play this game, the authority game. And I say, No, I have a responsibility to my job. I called my caseworker and said, “Please tell them I’m not coming in because I take my job seriously. My job is just as important as yours.”

I see my caseworker every Sunday. If you say, “What am I going to do for food?,” they tell you go to a pantry. Now, do you think that’s fair? Telling a person who works every day to go eat at a pantry?

You’re watching all forms of people come into the system. You got construction workers, post-office workers, bus drivers in the shelter. You got hardworking people in the system. And these people can’t find nothing. Something’s wrong when you start building more shelters instead of affordable housing. It’s almost like this is what they want; they want a system where people become needy. I don’t want to be needy. I want to pave my own way.

We’re building condos at 550 Vanderbilt. The prices on these condos is crazy — $900,000 for a one bedroom. They started moving people in, so I’m homeless but I’m sitting here building, watching people live good. Some of these people have three bathrooms. The marble, oh my God. The cabinets, oh my God. The refrigerators. These people will have gardens. The roof is such a good site, especially early in the morning. I was on the roof the other day, and you can see all of New York City.

I grew up in Brownsville. Born at St. Mary’s Hospital. So what happens to the people from Brooklyn? We’re moving over for the whole new Brooklyn.

The store manager who finally made it out.

Shaquanna Spence,

26 After living with her son, age 8, in a Win shelter in Flatbush, since October 2014, she moved into NYCHA housing last month.This is actually my seventh state that I’ve lived in. I lived in Georgia the most. That’s where I went to college. Prior to here, I was in Philadelphia. The guy that I was dating was arrested. I feel like I have a bad-luck ghost on me. We were living together; me, him, and my son, and everything was great, but after he was arrested, I was stuck with all the bills, all the responsibility, and it became overwhelming. I picked up a second job. I was doing McDonald’s in the morning and Burger King at night, but I couldn’t keep up with the bills. At the shelter-intake center, they had a room for me to go in individually, but they didn’t have space for my son. So I ended up catching a bus to New York, going to the Bronx and PATH, and going through that whole process. This is my first experience living in New York, inside a shelter.

I’ve been here since October 14, 2014. I started working in November of 2014, and I’ve been working consistently since then. When I first came here, I worked at Domino’s. I met a friend there. His family, they help me with my son. They watch him when I work. Until recently, I worked at Claire’s and Icing. They’re the same company. We pierce ears, sell accessories, etc. They’re right up the street. I was management. When I first was hired there, it was $9.20, then later $10.10. Realistically, you can’t survive on that in New York. Even if you worked 40 hours a week, you’re bring home under $500 biweekly. That’s $1,000 a month. Maybe your rent is paid, but now you can’t eat and your lights are cut off. It’s just a circle. They’re not helping us go out of the circle.

I’m in this program called “Back to Work.” If you don’t get more than 35 hours per week, you have to do the Back to Work program. You’re supposed to go there Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. If you’re working, they expect you to be there on your off days. Say, for example, I have to work five days out of the week, but I’m off two weekdays, those two days I have to be in the Back to Work. You’re supposed to be looking for new work. They do help you with résumés. They’ll tell you which jobs are available, but the jobs they’re telling you are available are the same jobs that got you in the predicament in the first place. Realistically, at a fast-food job, unless you’re a manager, you’re not going to make money. You’re not going to get hours. It’s almost as if they want us to come back.

With my particular job, you’re going to get all your hours during the holiday season, but then once the holiday season is over, people are not buying gifts, your hours drop. That affects you inside of here too. Say, for example, you received your pay stubs and they were low for the first couple of weeks, but then you start getting more hours. The way the system processes it, it’s almost as if they skip over the fact that you didn’t have funds all that time. They’re like, well, you got it now. Even with the particular job I have, I don’t qualify for benefits living in the shelter. You can’t get food stamps or case assistance. I’m living through the process of it, but I’m also living like I’m outside of the shelter, living a regular life, having to do the responsibilities. It kind of confuses me.

I’ve had five caseworkers. You don’t just get one caseworker because sometimes they leave. We have caseworkers in my shelter but you might not necessarily get assigned to one of them. Sometimes they schedule your appointments in different locations. I’ve had to travel to Manhattan, to Coney Island, to Queens. At the appointments, you’re not seen instantly, you’re there for hours. So now you have to take your child with you, and your child is now missing school, so they can attend an appointment with you to make sure that you’re able to live in the shelter still. If you don’t pick your child up from school on time, you can catch an ACS case, but if you keep your child out of school, they’re like, “Why was your child out of school?” It makes you feel like you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t. This is the “Gotcha, gotcha” part.

It can be overwhelming when you have to balance raising a kid, being inside a shelter, trying to make sure you work, and trying to build a career. I recently just passed out. My son had to call 911. He said that I was on the ground for four minutes from 2:28 p.m. to 2:32 p.m. I felt my body feeling strained, but I wasn’t going to go to the doctor. I had to because they called the ambulance, but f I could have, I would have avoided that because I didn’t want that bill. That’s kind of sad, but who wants to pay all these bills?

They told me that I was stressed out and fatigued. I haven’t been having an appetite. My tooth was hurting. I had an infection in my wisdom tooth, and they said it had to be pulled. It won’t happen anytime soon because it’s very pricey to get it pulled. My son and I, we still don’t have insurance. Every caseworker I’ve ever had thought that was strange. They’ll get us enrolled for Medicaid, and I’ll have it for two weeks and they’ll take it away and say something went wrong with the case. So I have to go down there and hound them and try to figure out what’s going wrong. We don’t need the food stamps or whatever to survive, but we do need health insurance. Even if I don’t get it, that’s fine, but I need it for my son.

I just moved out. I was picked for NYCHA. So I am moving to Bed-Stuy. That’s based on my income, and it can change.

There was a lady on the elevator the day we were leaving and she said, “Oh, you’re moving?”

And I said, “Yeah.”

And she said, “How long were you in here?”

And I said, “Oh, just two years, three months, two weeks, and a day.”

She said, “Oh, you were here much longer than me.” She had only been there seven months. I didn’t want to discourage her and say you have a lot longer to go because that might not necessarily be the case. Maybe she’ll get out sooner.

*A version of this article appears in the March 20, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been updated since it was originally published. A previous version of this article stated that Los Angeles and Chicago had higher homeless populations per capita than New York. Those cities’ homeless populations are higher only for the unsheltered homeless.

Additional reporting by Gabe Cohn

Design and development by Jay Guillermo, Terri Neal and Ashley Wu

Graphics by Ashley Wu

Inside Walker’s unit.

Other violations that can result in a case being “closed”: failure to seek other housing, to carry out an independent living plan, to participate in employment and training programs, to participate with child-support enforcement, to apply for Supplemental-Security Income benefits, or to maintain general shelter cleanliness; exceeding the personal bag limit; possession of alcohol; improper attire; excessive noise; disrespectful behavior; nonapproved visitors.

For forgary, weapons, and identity theft. He was released in 2015.

As of December 2016 all shelters are required to allow residents daytime access to the building.

Roughly a third of the city’s sheltered homeless have a high-school diploma or GED, and 15 percent have some college education.

Before a family or individual can enter the shelter system, DHS investigates to find out whether there are any alternate housing options already available to them. Homeless residents must also verify their relationship by providing birth certificates for their children.

Fifty-four percent of families who seek shelter are turned down.

A “short sale” is when the proceeds from selling a property are less than the debt owned on the property.

There are 21,600 homeless children in the shelter system.

Only 5 percent of shelters are run directly by the city. The rest receive city funding to shelter the homeless. At privately owned cluster sites, landlords receive in some cases $3,000 a month from DHS for rooms without a bathroom or kitchen.

Advantage was a temporary rental-assistance program implemented by the Bloomberg Administration in 2007. In 2011, after Governor Cuomo pulled the state’s share of the funding, Bloomberg discontinued it.

For Section 8 vouchers alone, there are 147,000 people on the waiting list in New York City, so many that in 2009, NYCHA stopped accepting applications. Last year, 800 homeless families moved with the help of a Section 8 voucher.

According to the Coalition for the Homeless, at least a third of homeless single adults experience severe mental illnesses or suffer from an addiction, or both.

The Bedford-Atlantic Armory Men’s Shelter in Crown Heights.

CHiPS is a 46-year-old nonprofit that operates out of a four-story brick building in Brooklyn. The kitchen serves as many as 250 meals a day, six days a week, on the ground floor, and on the three stories above there are seven units made available for mothers with infants.

The nonprofit Breaking Ground works to get the “unhousable” homeless into housing. It currently maintains 3,520 apartments in and around New York. Under de Blasio, a DHS program called HOME-STAT also sought to coax the chronically homeless into shelter. So far it has successfully found housing for 690 street homeless.

A division of the city’s Department of Small Business Services, Workforce1 centers provide free career services for New Yorkers, including helping to train and match job hunters with work.

Since 2010, the average length of stay for families in a shelter has increased from 248 days to 404 days.

Landlords are legally required to accept vouchers yet many do not. Last year the New York City Commission on Human Rights brought more than 120 “source of income discrimination” cases against landlords.

Fifty-five percent of homeless families in shelters have previously lived in shelters.

The Emergency Assistance Unit was once the initial point of contact for anyone trying to enter the shelter system. It was notoriously violent. In 2006, the Bloomberg Administration demolished the building and redesigned the intake system. In 2002, a 16-year-old boy killed himself when he learned that his family had to return to the EAU in the Bronx.

About half the city’s construction projects rely on union labor, compared to virtually all projects in the 1980s.

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) maintains 177,700 public housing units across the city. Last year, 1,800 homeless families received public housing, off of a citywide wait list of 270,000 people.

The upper income limit for a person living alone to qualify for public housing is $50,750 per year. For a family of four, the limit is $72,500.

A series of legal challenges starting in 1979 established a “right to shelter,” under which the city must provide temporary housing assistance for anyone who seeks it. Former mayor Michael Bloomberg claimed the rule attracted out-of-town homeless. DHS reports that in the first half of 2016, only around 2 percent of the 7,329 families that applied for shelter did not have roots in the city.

At $10.10 an hour, working 40 hours a week, with no vacations or sick days, annual income would be $21,000. Annual rent, at $1,500 a month, would be $18,000.

All homeless service clients who receive cash assistance and who are not already working a minimum number of hours a week are required to participate in the Back to Work job-training program or face losing their shelter.

It’s DHS’ policy to make on-site caseworkers available to all clients.

Inside Walker’s unit.

Other violations that can result in a case being “closed”: failure to seek other housing, to carry out an independent living plan, to participate in employment and training programs, to participate with child-support enforcement, to apply for Supplemental-Security Income benefits, or to maintain general shelter cleanliness; exceeding the personal bag limit; possession of alcohol; improper attire; excessive noise; disrespectful behavior; nonapproved visitors.

For forgary, weapons, and identity theft. He was released in 2015.

As of December 2016 all shelters are required to allow residents daytime access to the building.

Roughly a third of the city’s sheltered homeless have a high-school diploma or GED, and 15 percent have some college education.

Before a family or individual can enter the shelter system, DHS investigates to find out whether there are any alternate housing options already available to them. Homeless residents must also verify their relationship by providing birth certificates for their children.

Fifty-four percent of families who seek shelter are turned down.

A “short sale” is when the proceeds from selling a property are less than the debt owned on the property.

There are 21,600 homeless children in the shelter system.

Only 5 percent of shelters are run directly by the city. The rest receive city funding to shelter the homeless. At privately owned cluster sites, landlords receive in some cases $3,000 a month from DHS for rooms without a bathroom or kitchen.

Advantage was a temporary rental-assistance program implemented by the Bloomberg Administration in 2007. In 2011, after Governor Cuomo pulled the state’s share of the funding, Bloomberg discontinued it.

For Section 8 vouchers alone, there are 147,000 people on the waiting list in New York City, so many that in 2009, NYCHA stopped accepting applications. Last year, 800 homeless families moved with the help of a Section 8 voucher.

According to the Coalition for the Homeless, at least a third of homeless single adults experience severe mental illnesses or suffer from an addiction, or both.

The Bedford-Atlantic Armory Men’s Shelter in Crown Heights.

CHiPS is a 46-year-old nonprofit that operates out of a four-story brick building in Brooklyn. The kitchen serves as many as 250 meals a day, six days a week, on the ground floor, and on the three stories above there are seven units made available for mothers with infants.

The nonprofit Breaking Ground works to get the “unhousable” homeless into housing. It currently maintains 3,520 apartments in and around New York. Under de Blasio, a DHS program called HOME-STAT also sought to coax the chronically homeless into shelter. So far it has successfully found housing for 690 street homeless.

A division of the city’s Department of Small Business Services, Workforce1 centers provide free career services for New Yorkers, including helping to train and match job hunters with work.

Since 2010, the average length of stay for families in a shelter has increased from 248 days to 404 days.

Landlords are legally required to accept vouchers yet many do not. Last year the New York City Commission on Human Rights brought more than 120 “source of income discrimination” cases against landlords.

Fifty-five percent of homeless families in shelters have previously lived in shelters.

The Emergency Assistance Unit was once the initial point of contact for anyone trying to enter the shelter system. It was notoriously violent. In 2006, the Bloomberg Administration demolished the building and redesigned the intake system. In 2002, a 16-year-old boy killed himself when he learned that his family had to return to the EAU in the Bronx.

About half the city’s construction projects rely on union labor, compared to virtually all projects in the 1980s.

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) maintains 177,700 public housing units across the city. Last year, 1,800 homeless families received public housing, off of a citywide wait list of 270,000 people.

The upper income limit for a person living alone to qualify for public housing is $50,750 per year. For a family of four, the limit is $72,500.

A series of legal challenges starting in 1979 established a “right to shelter,” under which the city must provide temporary housing assistance for anyone who seeks it. Former mayor Michael Bloomberg claimed the rule attracted out-of-town homeless. DHS reports that in the first half of 2016, only around 2 percent of the 7,329 families that applied for shelter did not have roots in the city.

At $10.10 an hour, working 40 hours a week, with no vacations or sick days, annual income would be $21,000. Annual rent, at $1,500 a month, would be $18,000.

All homeless service clients who receive cash assistance and who are not already working a minimum number of hours a week are required to participate in the Back to Work job-training program or face losing their shelter.

It’s DHS’ policy to make on-site caseworkers available to all clients.