“Is Erik coming?” a man asked, as I hovered with a few people near the outdoor firepit on the roof deck of a luxury apartment building in Pentagon City on a frigid December night.

The Erik in question was Erik Prince, the notorious founder of Blackwater, the private security company. The gathering, well over Virginia’s COVID-era limit of ten people, was to honor Paul Behrends, a former congressional aide who had passed away unexpectedly the week before.

Prince and Behrends were close associates and friends for several decades; in his memoir, Prince even credits Behrends with helping to convert him to Catholicism. Behrends, in turn, tried his best to help salvage Blackwater’s public reputation after the company’s security contractors had massacred more than two dozen Iraqis at Nisour Square in 2007. (President Trump last week pardoned four of the former Blackwater guards convicted for their part in the killings.)

Behrend’s role in defending Blackwater was also why, at least indirectly, I ended up at this private gathering of his close friends in the middle of a pandemic. Behrends had first reached out to me more than a decade ago, when I was writing frequently about Blackwater for a security blog and deriding the company’s endlessly weird proposals to privatize wars, from leasing pirate-fighting ships to selling dystopian-looking blimps.

Behrends, who was lobbying for Prince’s company at the time, wanted to talk one day. The over-six-foot-tall former marine was all smiles when we met. He launched into details of the company’s trials and tribulations, never uttering the words off the record. His earnestness seemed mismatched for a company that was offering what one of its executives described to me as “one-stop shopping” for private military operations. Behrends immediately invited me to visit Blackwater’s training facilities in North Carolina. “You could bring a friend,” he suggested, as though it were a field trip to Disneyland. “Should be a lot of fun.”

The company’s senior executives nixed the trip at the last minute, and even though I never wrote a kind word about Blackwater or any of Behrends’s other endeavors, he always stayed in touch, providing a window onto a Wild West world of private security and international intrigue. He once described to me a meeting he and Prince had attended in Qatar to pitch Blackwater’s security services to a member of the country’s royal family while a black panther, the sheikh’s pet, paced in its cage behind them.

Behrends’s extreme openness was often what got him into trouble, but it’s also what made him likable, even if, sometimes, to the wrong sort of people. So when a friend of his told me about Behrends’s unexpected death and invited me to the informal memorial, I unwrapped a fresh KN95 and went.

Initially, I retreated to the outdoor roof deck to avoid the roomful of people, many of whom had flown in from abroad. None of them — except for me and the friend who had invited me — were wearing masks, a reminder of a pandemic that has taken on a weird political dimension. But as the toasts started, I went back inside, where about two dozen people, mostly men, were recounting stories of Behrends.

I slipped on a cloth mask over my KN95 and hoped for the best.

One of the first up was Dana Rohrabacher, the former 15-term Republican lawmaker who represented California’s Orange County. Behrends had served for many years as a senior aide to Rohrabacher, though the two were a bit of an odd couple: Behrends, the marine who came from a devout Catholic family in the Midwest, and Rohrabacher, the surfer, onetime folk singer, and early advocate of legalized marijuana. The Cold War brought them together. Rohrabacher told me he was serving in the Reagan administration when John Lenczowski, one of the architects of Reagan’s hard-line Soviet strategy, introduced him to Behrends, who was then still serving in the Marine Corps. Both Behrends and Rohrabacher believed in defeating the Soviet Union by any means possible, and they bonded over their trips to Afghanistan. But although they stayed together for the better part of 30 years, there were still some hints of the cultural gulf between them.

As Rohrabacher began his toast to Behrends, his friend and colleague of several decades, he mistakenly referred to him as a retired Army lieutenant colonel.

“Marines,” several people shouted out, even as Rohrabacher kept talking.

“First and foremost of everything, Paul was a patriot,” he said. “What was good for America, he was for, and if somebody threatened us or did something that would hurt our people or country, he was against them. It’s as simple as that.”

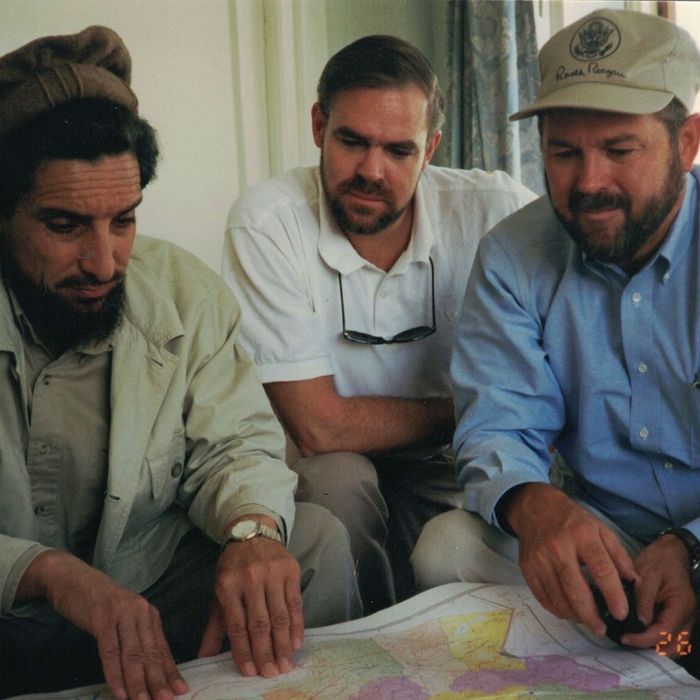

But it wasn’t always that simple — particularly in recent years, when Behrends started to show up frequently in the press. While never a household name, he was well known in Washington, D.C., particularly among those who dealt with foreign affairs. For many years, he was like the Forrest Gump of international intrigue, showing up in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion and then again after the U.S. invasion. He was in Yugoslavia as it began to splinter and after it fell apart, and then in Nigeria amid the fighting with Boko Haram, the jihadist group that kidnapped over 200 schoolgirls in 2014.

In many ways, his life was the stuff of movies, though whether you thought he was the hero or the villain sometimes depended on what side of the political aisle you walked along. He helped get weapons to the Afghan mujaheddin fighting the Soviet Union in the 1980s, landed Erik Prince an internship in Rohrabacher’s Capitol Hill office in the 1990s, and worked with the lobbying firm notorious for its ties to Jack Abramoff, who was on the invite list for the evening but didn’t show. (Behrends’s death at 62 was more straightforward than his life: While walking near his home, he tripped and hit his head on the concrete.)

In his toast, Rohrabacher recounted traveling with Behrends in the 1990s to Afghanistan’s Panjshir Valley to visit Ahmad Shah Massoud, the Northern Alliance leader who was killed by suicide attackers linked to Al Qaeda two days before the 9/11 attacks, as well as splitting off from an official congressional delegation to Vietnam that included Senators John McCain and John Kerry to traipse around the country for a week looking for American POWs (they didn’t find any). “We did some good things for America,” Rohrabacher said.

By 2017, the time of the Russia investigation, however, Behrends’s Forrest Gump image had morphed, at least for the left, into something more like that of a sidekick to people who appeared hell-bent on, if not undermining, then influencing, U.S. politics in favor of Russia. Both Behrends and Rohrabacher had gone from Soviet hawks to seeming Russian enthusiasts. At every twist and turn of the Russia investigation, there was Behrends — with Maria Butina, the redheaded foreign agent; Natalia Veselnitskaya, the Russian lawyer from the infamous Trump Tower meeting; and even Julian Assange, the WikiLeaks founder who had served as a conduit for election-related material hacked by Russian intelligence.

Suddenly Behrends’s motives — to his critics — seemed more nefarious, and when people heard his name in recent years, it was in connection with the Russia probe, particularly since he had worked for Rohrabacher, who, because of his history of pro-Russia stances, was frequently referred to in the press as “Putin’s favorite congressman.” And after Behrends was fired from his job as staff director of a House foreign-affairs subcommittee over his Russia contacts, Politico wrote about him with the headline “The Hill Staffer at the Center of the Russia Intrigue.”

Whatever one thinks of Behrends, his life and death span a critical time in America when the Republican Party went from cold warriors fighting the Soviet Union to suspected Russian assets accused of selling out the United States. By any historic measure, it’s a strange and dizzying turn of events. It’s also likely, soon, to come with some payback: As President-elect Joe Biden enters the White House, he will come with the baggage of a son under investigation for his business dealings (including with China), and Republicans are unlikely to let that rest until they get their own version of a Mueller investigation. While foreign influence has always been present to some degree in Washington, there has never been less agreement about which foreigners are okay to meet — or to do business — with. Now the party lines are increasingly drawn along two countries that few in politics would have considered directly speaking with 30 years ago.

“All those people who talked about Russia these last years, it was all instigated by people who were getting rich off China,” Rohrabacher said at the gathering. The real threat now, he continued, came from China and the “Bolshevik billionaires who are trying to take over this country,” a reference to the unnamed rich donors he holds responsible for ousting him from Congress in the 2018 election.

The former congressman made only an oblique reference to the Russia investigation, which likely contributed to his defeat, saying people “cannot get themselves out of the Cold War.”

It was a sentiment echoed by others who knew Behrends. “He was not someone who had a knee-jerk reaction of ‘Fuck you, Russians,’” an associate who asked that I identify him only as a former Soviet military officer, told me a few days after the memorial. “He was concerned very much about China. He thought the U.S. and Russia could work together.”

One of the ideas for U.S.-Russia cooperation, according to the former Soviet officer, was to help hunt for Russian POWs rumored to still be in Afghanistan after the Soviet withdrawal more than 30 years ago. Behrends, the associate said, told him he had conducted interrogations with Russian POWs during the 1980s Soviet-Afghan war. “I do have some notes that are not classified,” Behrends had said, according to this man. “I have some photos of these people.” After Behrends was kicked off the foreign-affairs subcommittee, however, the idea never moved forward.

That brought me to another question: What exactly was Behrends doing in Afghanistan in the 1980s? Even his friends weren’t quite sure. One said he had gone as a private citizen, another suggested it was perhaps for the CIA, and a third admitted they had no idea. When I called Rohrabacher the week after the funeral to ask, he told me, “There was no such thing as a concerned citizen in Afghanistan. In those days, we were part of a group of Americans who were taking things into our own hands.”

As much as Behrends’s life seemed to invite intrigue and scandal, it also attracted a hard-core set of friends. Prince never did show at the gathering (he was a pallbearer at the funeral), but the people in the room that evening had flown in from around the country and, in some cases, around the world. Many stood up to share stories about Behrends. Rohrabacher described how Behrends had saved him from nearly drowning while surfing off the coast of Chile, another person related how Behrends had launched their career in security contracting in Iraq, and a third recounted a drunken escapade with a young Behrends while in the Marines when they witnessed a private-airplane crash and attempted a rescue. Several broke down in tears as the rest listened attentively, interrupted only occasionally by a dry cough from an unmasked Rohrabacher.

It’s hard to find anyone, even among Behrends’s enemies, who could ever recall him being unkind to anyone. He raised his four children alone after a divorce, yet those at the gathering recalled him as someone who always found time to help out a friend. That same loyalty, said one of his friends, was what made him stick by Prince.

“I see the Blackwater saga as a prime example of Paul standing by a friend through thick and thin when no one else would,” another friend of his wrote to me. “In addition, he really felt the contractors in Iraq were serving honorably, defending diplomats (and members of Congress), and that they were being unfairly used as a scapegoat by those opposed to the Iraq War.”

More recently, Behrends had grown critical of Prince in private. A few years ago, I attended a small dinner with Behrends and a few of his friends, including Prince, at a since-closed Belgian restaurant in D.C.’s Logan Circle. I listened quietly as the group discussed their thoughts on George Soros’s international influence and Prince’s plans to privatize the U.S. war effort in Afghanistan. After Prince left — shortly before the check arrived — Behrends told me he was frustrated by his friend’s latest publicity tour. Prince, he said, was causing problems by attaching his name so publicly to the Afghanistan plans. “It’s always about Erik,” he groused.

Shortly after that dinner, Rohrabacher lost his reelection bid, and thus Behrends lost his own job on the Hill. Finances were tight, and Behrends, according to his own account and those of his friends, had spent well over $100,000 on legal bills in the Russia investigation. In his toast to Behrends, Rohrabacher lamented that they both had left government service “basically broke.” The two of them set up a consulting firm together in hopes of reversing their fortunes a bit.

There was little evidence that the reversal worked. Behrends’s friends whispered about the firm’s financial problems, and when I met up with him for drinks one evening at a bar near the White House before the pandemic hit, he asked how much I thought they could get for renting the parking spot at their office on Capitol Hill — hardly a sign of a booming business.

Behrends occasionally wrote to me to pitch a story on behalf of one of his clients, like Marsha Lazareva, a Russian businesswoman jailed in Kuwait on fraud charges. I politely declined because, among other reasons, I had recently commissioned and edited an article detailing the case against her; she did not come off well. As always, Behrends didn’t take it personally.

After Behrends’s death, I asked J. Michael Waller, who had known him since the 1980s, to help explain the transformation of a Soviet hawk into, well, something of a Russia gadfly. Waller said this was just an extension of Behrends’s Cold War work. “Paul did some back-channel work, which was one of the reasons why he would meet with so many controversial and disreputable people. Because somebody had to,” Waller said. “He would build these relationships partly because he’s a contrarian and very sociable and very curious, but also because he knew in the national interest somebody had to be a bridge of communications.”

For Waller, a senior analyst for strategy at the Center for Security Policy, Behrends’s ability to speak to everybody, whether a journalist, a suspected Russian spy, or an Islamist, was an asset. “He could bridge all of that for some reason,” Waller said. “He was still an unswerving supporter of Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Uighurs, or the underground Christian Church in China. Yet he could still have dinner with the bad guys who were doing all the bad stuff to the people he cared about and not betray his friendships and ideals.”

“Paul,” Waller said, repeating a statement Rohrabacher once made, was “fighting for freedom and having fun.”

In the last few years of his life, however, that philosophy seemed to be causing him ever more problems. One day, in the middle of the Russia investigation, Behrends called to invite me to lunch at the café in the Sculpture Garden, a place popular with D.C. tourists and congressional staffers looking for a quick bite.

He was upset, he told me, in a rare moment of looking downcast. One of his sons had created a Google alert for his name and was horrified each time his father showed up in connection with the Russia investigation.

What, he asked me with his typical earnestness, should he do? I stared blankly for a moment until I realized he wasn’t assailing the press coverage of the Russia investigation, some of which I was involved in. He genuinely wanted my advice.

“Perhaps,” I said, “you should be a little more careful about who you meet with? Some of these meetings, well, they look bad.”

He furrowed his eyebrows, considering this suggestion, but I could see it didn’t quite register. He saw nothing wrong with meeting with the strange cast of characters who entered and exited the Russia investigation like Star Trek redshirts, because that was what he had done his whole career.

Toward the end of the lunch, we chatted about his upcoming travel plans. He was leaving for Paris the following week, he told me.

“Vacation?” I asked.

“No, MEK,” he said, a reference to the Iranian exile group Mujaheddin-e Khalq, which used to be on the official U.S. list of terrorist organizations and is committed to overthrowing the government in Tehran. In more recent years, it has made inroads into American politics, particularly with Republican figures like John Bolton and Rudy Giuliani.

MEK wasn’t paying Behrends, but it was picking up the tab for the work trip to France. And even though MEK has been off the terrorist list since 2012, it struck me that, like his meetings with various Russians, this was the very sort of thing that would be picked up by the press and trigger his son’s Google alert.

“Have fun,” I said, unsure of what else to add.

I’m sure, in fact, that he did.