Sam Quinones has covered gangs, crime, and the border for 35 years, including a ten-year stint at the L.A. Times. He established himself as a leading voice on the opioid epidemic with the 2015 book Dreamland, which told the story of how prescription-drug companies and a sophisticated black-tar heroin operation in Mexico wreaked havoc across the U.S. In his follow-up, 2021’s The Least of Us, Quinones focused on the rise of two synthetic drugs: fentanyl, which had become ascendant in the intervening years, and a frighteningly potent form of meth that can quickly inflict tremendous damage on users. The extreme effects of these drugs, Quinones believes, has worsened the homelessness crisis in America. Recently, New York mayor Eric Adams unveiled a controversial plan to address that crisis by removing some people from the street involuntarily. I spoke with Quinones about the ravages of meth and fentanyl, how they have exacerbated social problems around the country, and what local and federal governments can do to stem the problem.

In your book The Least of Us and in an Atlantic piece last year, you wrote about the rise of very pure meth, which is produced in a different way than the variety that used to flow into the U.S. The effects have been devastating, but this still seems like a fairly under-the-radar phenomenon. Has it gotten more attention since you wrote about it?

My book highlighted this problem that people were seeing all across the country, and now people are trying to understand why it’s happening. And I think more and more people are coming to the conclusion that the meth coming from Mexico is being produced with much more potency. It used to be that a lot of the chemicals they couldn’t eliminate from the process were acting as diluting agents, and so people weren’t getting 99 percent meth when they bought this stuff; they were getting 50 percent or something like that. And now what you’re finding is that new ways of making meth get it to almost 100 percent. That’s very difficult for a human brain to accommodate. I think all of this is coming out now, because the book shone a light where none existed before and showed that people are in fact entering into extreme psychosis. And once they stop using the drug, it takes a long time to move beyond it and for the brain to heal — months, perhaps. It’s not a day-to-day thing.

I’ve been hearing this from people who are chemists, people who are in law enforcement. With the attention from the book, you’re finding people who are in a position to do the kind of research that I am not in a position to do. As I said in the book, and as I’ve said pretty much every time I talk about this, I’m not a chemist. I’m not the scientist to understand why this is happening. I’m just the reporter saying this is happening, and it’s happening all across the country.

You’re describing a social-fabric problem that’s been exacerbated by the availability of these extremely pure drugs that weren’t around before. That applies to fentanyl too — heroin was bad enough, and now there’s something much stronger.

And they’re similar in another way, too, and that is that both of these drugs don’t correspond at all to what consumers are demanding. They correspond almost entirely to the interests, the profits, the lower risk of the drug traffickers involved. They don’t need land, they don’t need rainfall, they don’t need sunlight, they don’t need farmers, they don’t have any seasons. They can produce year-round as long as they can get the ingredients. And that’s the key thing. Mexican traffickers have been able to get ingredients from the world chemical markets through two ports in particular, but several ports probably overall, that allow them to make these quantities that are now covering the United States coast to coast. That’s never happened before.

You write a fair bit about homelessness and how it intersects with drug addiction. You’ve observed that this meth renders people shells of themselves very quickly. Does fentanyl have the same effect? And how do those two drugs, in your view, exacerbate the problem of people living on the streets in places like L.A. and Portland, Oregon?

Both of them are intensely addictive, and both of them do a masterful job of what every drug of abuse has always done, and that is to hijack our instinct for self-preservation. These two drugs come in such enormous quantities and have such staggering potency that they do the job far more masterfully than drugs have done it before. So you have methamphetamine that is driving people to homelessness and becoming incoherent and irrational and delusional and paranoid.

Fentanyl is highly, highly addictive, and it’s basically ridding our country of heroin. There’s very little heroin on the streets of America anymore, which is an amazing thing to say. Fentanyl has essentially outcompeted it. Both of those drugs, together and alone, make it so that people will literally refuse treatment, will literally refuse housing even when they’re living in tent encampments, even when they’re living in feces, in lethal temperatures, beaten, pimped out, because they do such a masterful job in potency and in supply of keeping, of thwarting that instinct to self-preservation.

Are there any places that have taken a particularly effective or ineffective approach to this problem in your view — dealing with the humanity of these people whose lives have been shattered while getting them off the streets and somewhere better?

This is such a new problem, and we’ve been consumed with COVID for the last two years. Fentanyl was really mostly in the Midwest, and it was only by 2018, 2019 that it had really spread to both coasts and every place in between. Meth has been marching across the country in these staggering supplies since about 2012 or 2013, I would say, but it’s also a drug that really doesn’t create the headlines fentanyl does.

Because it doesn’t kill people as quickly, right?

It doesn’t kill people. It’s also, like, the pure raw face of addiction — people out of their minds wandering in the streets, screaming naked like some Allen Ginsberg poem. It’s something that people would prefer not to have to face, I think. It’s easier to send condolences to someone who’s dead than to deal with someone who is out in the streets out of his mind. And so when it comes to meth, there hadn’t been the recognition as a major source of problems in so many parts of the country until my book came out. We’re all still talking about the opioid epidemic. And with fentanyl, it hadn’t reached national proportions until just before COVID hit, and then COVID took up all the conversation for the last two years.

We are just now trying to figure this all out. You’re seeing San Diego, you’re seeing L.A., you’re seeing New York and different places try to deal with it in one way or another. But it seems to me to have surpassed, in some fundamental way, the ability of any town or county to do much about it. It seems to have graduated to the level of the State Department or a national emergency, where it has to be dealt with via international diplomacy. Seriously, I mean, when you’re talking about the supply as being the major issue here, and I think it absolutely is, you’re standing in the tide and trying to keep the tide from going out. Since all this has developed, Obama, Trump, and now Biden — none of them has really dealt with this issue the way I think, internationally, it needs to be dealt with.

The scourge of meth and fentanyl is happening at the same time as a movement to legalize softer drugs. Marijuana is legal in 21 states, and Colorado legalized mushrooms last year. There’s long been a small group of people who want to go further and legalize everything with the idea that it would be a way of reducing suffering and also deal a blow to sellers. I believe you’re against that approach of decriminalization of fentanyl and meth. Is that right?

I’m not necessarily against it. I’m saying that it doesn’t seem to make sense in a time of fentanyl and methamphetamine. You’re allowing people to remain on the street selling a drug that they know will hurt somebody and almost certainly kill somebody. To me, that is not a tenable solution long-term. And I think you’re seeing why as people die, because families are like, “Well, why are you allowing this?” They have a stake in this too. Their loved one died.

Does that extend your view of something like safe-injection sites, which New York is experimenting with now?

I don’t believe we’re in a time where we should say no to any solution. I think we’ve got to try a lot of different things. But keeping people alive by reviving them with naloxone has its own risks. And the risks are that you will, over repeated overdoses, damage your brain, because your brain is getting a deprivation of oxygen each time you go into overdose. You’re seeing this now all across the country — we’ve probably never seen so many people overdose on an opioid in the history of the planet as have overdosed in the United States. And then so many of them are revived. But we’re seeing now that this is not risk-free — that you now have people who are overdosing and developing brain impairment.

I suppose there are ways to run those sites in ways that avoid overdose. But the idea of having a policy that says, “Well, we’re going to provide for you until you are ready for treatment,” flies in the face, I think, of a reality where people are on the street, living in degradation and exploitation of the most rank manner. So to me, it’s an idea that maybe we should try, but I think we also need to have some real ideas. I think we need to keep in mind that keeping people on the street is going to be a death sentence. There’s a saying on the street, and I’ve heard it from several people, that there is no such thing as a long-term street-fentanyl user like there was with heroin. There are people who use heroin for 30, 40 years, but with fentanyl, everybody dies. There may be people using it who function in society to some degree, but eventually, everybody dies.

And the other part of fentanyl that I think safe-injection sites need to deal with is the fact that it’s a fantastic anesthetic. I’ve had fentanyl myself — used in surgery, it is a revolutionary drug that has made many surgeries possible that weren’t before. One way it does that is potency, but another way it does that is that it gets you in and out of anesthesia very quickly. That’s the whole benefit of it. Within minutes of having my surgery, where I had a stent put in, I was lucid, talking, “Hello, how you doing?” That was not the case with morphine.

And I would say that the mere fact of its ability to bring you in and out very quickly of its effects is what makes it an absolute torment for users. So people who would inject or use heroin twice or three times a day are now finding that they have to use fentanyl four, five, six times a day. That means you basically have to live near the safe-injection site. Your life has to revolve around it. If you have to use fentanyl four, five, six times a day, you’re never really moving anywhere away from those sites. That’s something like every two, three hours. It’s exactly that component of fentanyl that makes it an enormous boon to drug dealers and traffickers, because now you’ve got people who have to use more often. If they had to use a certain amount of heroin to stay well through the day, to keep the drug sickness away, now you’re seeing them use maybe two, three times as much fentanyl.

That means more sales and a more regular customer for the traffickers. It’s a torment for users. This is about supply creating demand. There’s no heroin addict in America who wanted to be a fentanyl addict. They were transitioned to fentanyl by mixing it into the supply either sloppily or intentionally, and I think a lot of both. And now you’ve got a whole bunch of people nationwide that are using and demanding fentanyl.

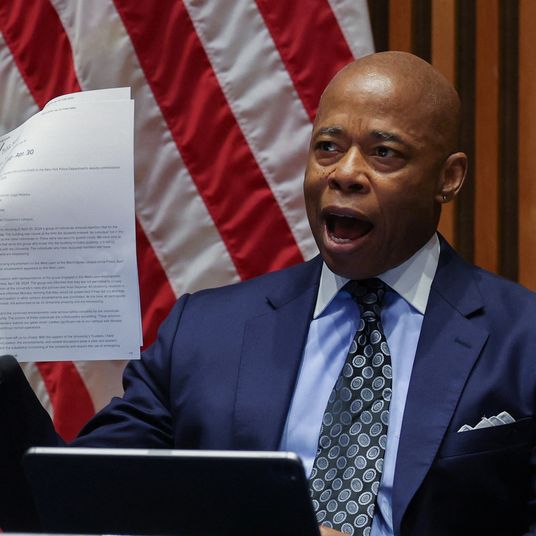

New York mayor Eric Adams recently announced a plan to remove some people from the streets involuntarily. Does that kind of approach strike you as wise?

Well, I suppose the devil’s in the details in all this stuff. If you provide a place where people can’t leave, where they receive significant treatment and a continuum of care that lasts, then I’d say, yeah, this is what needs to happen. If you’re just saying, “We’re going to take you out of the street, put you in a place where you can’t leave, but you’re just going to sit there,” I’m not sure how that’s going to help anybody in the long run — either the city or the person. This debate over involuntary commitment was not really the debate it is now before fentanyl and before methamphetamine. And I believe that’s very natural, because these drugs have clearly made it so that people are, without a doubt, incapable so often of caring for themselves. And what’s more, they provide real public-health hazards through tent encampments and just being on the street. There’s more than just that person whose safety is at stake, it frequently seems to me. But it just depends on how you do it. And I suppose that that’s what the City of New York’s going to be dealing with.

Have you seen any promising approaches in terms of cutting out the supply of this stuff? Has anyone come up with any kind of workable idea?

No. I lived in Mexico for ten years — 1994 to 2004. I wrote two books about the country. But at no point in the history of the so-called drug war have we seen the kind of collaborative efforts that must take place, that can take place, between Mexico and the United States nationally. And it seems to me that this has to do with complicated issues of history and goes back a long, long way.

But I do believe that this now requires a collaborative relationship between the two countries but one that does not tiptoe around the truth, which is that Mexico has a real problem with deep corruption in the criminal-justice system. And we have a problem with guns that are being bought here and smuggled south into Mexico — principally, assault weapons. The wars between the Mexican drug-trafficking groups erupted in 2005, one year after we allowed our ban on the sale of assault weapons to lapse. That ban lasted from 1994 to 2004. It’s not that they couldn’t get access to assault weapons; it’s just that the numbers were not what they are now.

So they have their issues with corruption. We have our issues with gun trafficking and gun flow. And both of those are part of what creates the impunity down in Mexico that allows these guys to create huge quantities of methamphetamine and fentanyl that now cover the country. I believe this needs to be handled with far more urgency than it ever has been by any American president — and certainly by the Mexican authorities as well. It needs to be made into the issue that it should be, that it can be. And without that, it’s almost like any city or county is, again, going to be out in the middle of the ocean trying to keep back the tide.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.