This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

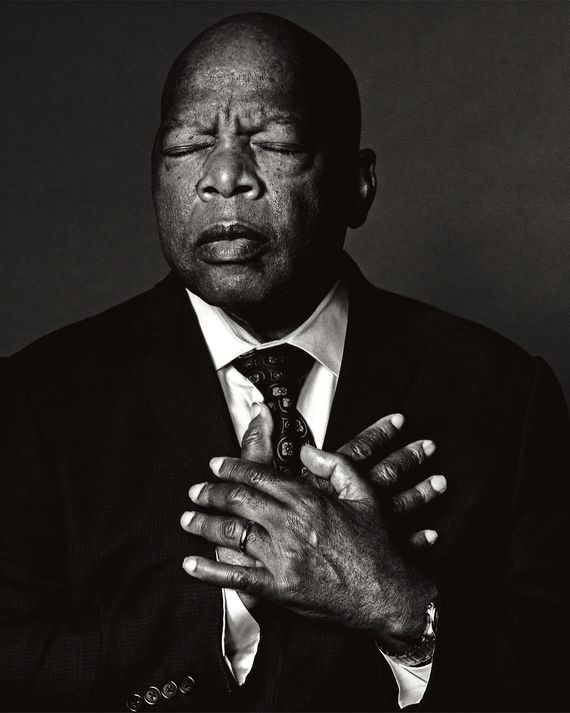

John Lewis died on Friday from complications due to pancreatic cancer, an illness that divided the last few months of his life into “good days and days not so good,” as he recently told me. He’d seen a lot in his 80 years — from a modest youth as the third of ten children in an Alabama sharecropping family, to a brutal and exhilarating early adulthood in the civil-rights movement, to his storied tenure in Congress, where he represented Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District from 1987 until his death. His later years were marked by novelty, much of it lamentable: the election of Donald Trump, who he believed was the worst president for civil rights in his lifetime, and his cancer diagnosis in December, less than a year before he had a chance to see Trump voted out of office. Neither the ups nor the downs much swayed his sense of optimism. Even its most recent test — the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and the protests, rioting, and often violent police crackdown that followed — engendered in Lewis abundant cause for hope. Just over a month before his death, Lewis spoke to New York about why he’d stayed the course for so long, even as timeworn political strategies seemed inadequate to fixing urgent social problems, and he openly feared waking up one day to find that American democracy had disappeared. This instinct to be vigilant, but stubbornly hopeful, was, for many, among his most inspiring traits. He remains in death an example of what can be won if one is willing to make, in his words, “good trouble.”

I’m curious, watching what’s happened this past week or so, what has stood out to you?

This determination of the young people, even not so young. Not just in America, but all around the world. I’ve come in contact with people who feel inspired. They’re moved. They’ve just never been along in a protest — they’ve never been in a march before — they decided to march with their children and their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and to walk with them. They’re helping to educate and inspire another generation of activists. It’s seeing an effect. There can be no turning back; there can be no giving up.

When you were protesting in the 1960s, was it an intentional strategy of yours to provoke white violence against yourself?

First of all, we believed in the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence. We had attended nonviolence workshops. When we were beaten, arrested, and taken to jail, we never struck back. We said, If you’re going to beat us, in effect, let it be in the daylight. So people can see what is happening. And we used our bodies as witness against segregation and racial discrimination. The philosophy of nonviolence became a way of life. A way of living.

When I was arrested the first time, in 1960, I felt free and I felt liberated. I felt like I had crossed over. And the local authority, the local officials, they couldn’t fight us by putting us in jail. So we filled the city jails in Georgia, in Tennessee, and all around the South. And people around the country didn’t like what they saw, seeing these young, well-dressed black students being arrested and taken to jail.

What people did then, it appealed to the conscience of the American people. People couldn’t take it. They couldn’t understand it. Taking the beating and thrown in jail. People pouring hot water, hot coffee on us. We changed the attitude of hundreds of thousands of people.

It seems to me that the same kind of imagery is what’s required today to spur action for a lot of people. Why do you think that is, more than 50 years later — that the most persuasive ways to create a sense of urgency for racial-justice causes is for lots of Americans to see images of black people being beaten and harmed and killed?

Well, even today, I think people are moved all these many years later. They’re moved and inspired to see people moving in an orderly, peaceful fashion. That people are willing to put their bodies on the lines for the cause.

One of the most striking things in the documentary is that you’re very driven by your faith and a sense of optimism. When have you been most hopeless?

Studying and being trained in the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence, it helped to make me stronger, wiser, gave me a greater sense of determination, and if it hadn’t been for my coming under the influence of Martin Luther King Jr., James Lawson, and wonderful, wonderful colleagues, students, the young people … I don’t think I would have survived the beatings, the arrests. We became a family. We depended on each other. And if I had an opportunity to do it all over again, I would do it.

Have you had a moment where you felt that maybe this wasn’t working?

No, I never ever came to that point. You get thrown in jail, maybe for a few days, and then you go to Mississippi, and you go to the state penitentiary, and you find some of your friends and your colleagues. And you get out, and you go on to the next effort. We used to say struggling is not a struggle that lasts for a few days, a few weeks, a few years. It is a struggle of a lifetime.

You mentioned when you were arrested, it was a liberating experience. From my experience with activists today, I don’t get the sense that a lot of them feel the same way.

Well, no one in his or her right mind would like to be arrested and lose some freedoms or go to jail for a few days. But during the movement, we were taught it’s part of the price that we would pay for trying to liberate our brothers and sisters, our mothers and fathers, our grandparents and great-grandparents.

Have you watched any of the videos that inspired the protests? For example, the video of Ahmaud Arbery being killed or the video of George Floyd being killed?

Yes, I have. Makes you cry. Makes you sick. You say to yourself, How many more? How long? How long? That’s why I’m very hopeful. That’s why I’m really optimistic about this upcoming election. [President Trump] cannot tell a lie over and over again when people have the photographs, the videos.

Do you think it’s important for people to watch these videos? Or is it enough for them to just know what’s contained in them?

I think it’s important for some people. All of the people cannot take it. They become bitter, hostile. Some of them just give up; they drop out. I kept hearing people saying, “I can’t take it any longer. I can’t take it anymore.”

Do you ever get angry about this stuff?

No, I don’t get what I call angry. Every so often, I have a sense of righteous indignation, and I just feel like if I was the same John Lewis as John Lewis a few years ago, I would be out in the street.

What do you do to keep from becoming bitter?

I pray over and over again, have what I call an executive session with myself, just self-listen: This is what you must do. This is what you must say. Do what you can, and play the role that you can play.

So much of your life’s work has been dedicated to advocating for the importance of voting and effecting legislation to end racial inequality. And yet racist violence at the hands of law enforcement is a constant, really, no matter which political party is in power. How much of these problems is it possible to solve through voting and legislation?

A great many of these problems we’ll be able to solve through the power of the ballot. The vote is the most powerful nonviolent tool we have in a democratic society. And it’s why people didn’t want people of color to come register to vote, because you have power that you can use.

We have, in a lot of the cities where this unrest is happening today, progressive mayors, progressive city councils, and yet law-enforcement violence occurs regardless of who’s in office. I just wonder, Where should concerned Americans be directing their energy when voting the right people, or who they think are the right people, into office doesn’t seem to be solving the problem?

We must never ever give up, or give in, or throw in the towel. We must continue to press on! And be prepared to do what we can to help educate people, to motivate people, to inspire people to stay engaged, to stay involved, and to not lose their sense of hope. We must continue to say we’re one people. We’re one family. We all live in the same house. Not just an American house but the world house. As Dr. King said over and over again, “We must learn to live together as brothers and sisters. If not, we will perish as fools.”

Do you have any advice or thoughts for communities that are looking for ways to reform how policing is done where they live?

It is my belief that we must work on a national level as well as a local level. That we need to humanize police forces, humanize the people, whoever is in charge of the police department at the local level but also at the national level.

Can you tell me what you mean by “humanize”? Do you mean we need to understand that they are humans too?

Well, I mean that we all are human beings, and we must be treated like human beings and respect the dignity and the way of each other. What happened in Atlanta with the officer beating up two young students was uncalled for. And I think the mayor and the police chief did the right thing, and they didn’t wait — they did it right on the spot. Of course, officers of the law didn’t have a right to abuse other people’s right. You have to be human.

Do you think there are major philosophical differences between the way that your generation viewed the struggle for civil rights and the way today’s younger generation views it?

Well, I wouldn’t say there are major differences. I think my generation of young people was greatly influenced by the teachings of Martin Luther King Jr. and by individuals like James Lawson. And we dedicated ourselves to creating what we called the loving community. We wanted to do what we called “redeem the soul of America.” We wanted to save America from herself.

The fact that you bring up restoring the soul of America is very interesting, because that’s similar to one of the major slogans for Joe Biden’s campaign for president. At the same time, he’s been running a campaign promising to return things to normal or the sense of normal that existed before President Trump. Is this a message that Democrats should be running on right now? A return to normal?

I think Democrats should be preaching a message of hope, that we are going to inject something a little more meaningful into the very vein of our politics, into the very vein of our Democratic ideas, and make it possible for people to be a little more human, humanize our government, humanize our politics.

It’s become clear, especially in recent years, that the task of legislating can be a very, very slow process. And depending on how strong your opposition is, it can be almost impossible for long stretches of time. Did you ever feel that you made faster progress as an activist than you do as a legislator?

Oh yes. You have to find ways from time to time to dramatize, to make real the process that we’re in the process of making. You have to find ways to inspire, educate, and change people. And you have to continue to center people.

Do you ever have regrets about making the jump from pure activism to becoming an elected official yourself?

No, I don’t have any regrets. I feel sometimes that there’s much more that we can do, but we’ve got to organize ourselves and continue to preach the politics of hope, and then follow our young people, who will help us get there. And we will get there. We will redeem the soul of America. We will create the loving community in spite of all of the things that we witness. The past few days, it made me very sad. There were times I wanted to cry, but the tears wouldn’t come.

The signature legislative accomplishment that you’re most associated with was before your time in Congress — the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

I’m very, very proud that I played a role in helping to get the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed.

Having been so involved in the push for voting rights, what was it like for you personally to see the Voting Rights Act get the treatment that it got by the Supreme Court in 2013, with the elimination of the pre-clearance formula?

Well, it made me very sad. I gave a little blood on that bridge in Selma to get the Voting Rights Act passed. But things are going to change again. I’m convinced that we have the ability, we have the capacity, to hold on to the House and take the Senate.

Looking at the language of the Voting Rights Act, do you think there were any flaws in its original writing that prevented it from being more resilient against the attacks it has faced recently?

Well, I think the original drafters of the act, those members were trying to get a bill through Congress that would be supported by the majority. But we need to fix it. My idea back then was “One person, one vote.” Make it simple. Make it easy.

Does that mean no Electoral College?

Well, if it was left up to me, there wouldn’t be one.

Since the Voting Rights Act was passed, you’ve seen a lot of presidents come and go. Who do you think has been the worst president for civil rights since the 1960s?

The worst president for civil rights since the 1960s? Without a doubt, it is this president.

President Trump?

Yes. Without a doubt. I don’t think there’s any debate there.

He’s only been in office for three years. It seems like he hasn’t had nearly as much time as, say, Nixon or Reagan.

Well, he’s been uncaring, insensitive to the problems and issues in front of him, especially when it comes to issues of civil rights.

Is there another president who comes close?

I couldn’t name another one that comes close.

Wow.

I wouldn’t put anyone close to him.

What are you most worried about if Trump wins in November?

Well, I must tell you, I don’t worry about it because I truly believe that he cannot and will not win. People can only take it so long.

How worried are you about voter suppression in November?

I am concerned. I think there will be some attempt to oppress voters, but to steal elections, I don’t think they’ll get away with it.

What makes you so optimistic when Trump has already won once and when voter suppression has been used successfully, at least at the state level, for the past ten years?

Well, I’m convinced a great majority of people are watching what is happening, how it’s happening. I think the word will go out that people are watching, and you cannot get away on this one.

The Republican Party seems to have become a party that is largely uninterested in governing in a bipartisan way. What does this tell you about the future of bipartisan legislating?

It may be almost impossible. But the way things look now, I think we’re gonna pick up seats in the House, become a greater Democratic majority. And I believe we will take the Senate back. Then we should be a more effective body.

Do you think that reparations are on the table and politically possible once that happens?

I think it is a piece of legislation that will be considered, and there will be support for it. It could take time to educate enough people and get enough members that will be committed, and in Senate quarters, there’ll be strong opposition. But it’s something that we need to put on the House floor, and the Senate’s floor, and debate. In light of what has happened in the past — I tell ya, people should be prepared and ready to engage in a debate.

What has been your most hopeful moment as a legislator? The time when you think things have come the closest to the vision that you were advancing when you were an activist?

Well, the chance to pass legislation to recognize the contribution of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — I think that was a major accomplishment, making Dr. King’s birthday a national holiday. For all of the schoolchildren all over America, to many people around the world, they would know that this young African-American made a major contribution to have set the American house in order.

The price of his incorporation into mainstream reverence has been a lot of misuse of his legacy. I wonder what you think about the fact that anytime there is a peaceful, nonviolent racial-justice protest, there are a lot of people who use Martin Luther King as a cudgel against protesters, saying, “Dr. King wouldn’t have wanted you to do this because it is drawing attention to issues that divide people instead of bring them together.”

That Martin Luther King Jr. believed in action. He believed in people being engaged. He believed in people carrying the ability to say “yes” when they may have the desire to say “no.” He preached the philosophy of nonviolence, but he also was a man of action.

I’m sure you’ve seen that President Trump has become increasingly authoritarian in regard to the protests, with his threats of deploying the military. What do you think Congress’s role is in keeping protesters safe from him, and what solutions are you and your colleagues considering?

Well, I know there are ongoing discussions right now about what role we should play and what we should set in motion to protect the human rights and legal rights of all of our citizens.

Can you give any details on what those involve?

No. It’s still in its early stages. People are still discussing it.

I know that a lot of the younger members of Congress really look up to you and have reached out to you for advice. Can you tell me what those conversations look like? Who has impressed you the most from this younger generation, people like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley?

Well, I shouldn’t get into the business of naming names. Many of these people that are young, and some not so young, we’ve become friends. We talk over the telephone, on the floor of the House, different times and places. They’re so smart. They’re so gifted. Their minds are their own; they know where they’re going. Sometimes I feel like saying, “Pace yourself. It’s all going to work out. Don’t burn out.” They’re in a hurry, and we all should be in a hurry. We don’t have time to waste.

In my younger days, I said, “You tell us to wait and tell us to be patient. It cannot wait. We cannot be patient. We want our freedom, and we want it now.” And so, when I hear the young people, it’s not new for me. It’s very inspiring and uplifting. I think we need people to come along every so often who have the energy and the fire to push and pull.

Have any of them come to you to talk about their frustrations with maybe not being able to move the party in the direction that they wanted to move in?

Well, young members come and talk and I listen. From time to time, on some issues, I may say, “Go with your gut. Go with your conscience. Don’t burn yourself out. We have to live with the decisions we made.”

What do you say to people who have decided that the two-party system of voting doesn’t accomplish the goal of ending racial inequality?

My recommendation is don’t give up on the party, hang in there, and let’s have changes from the inside. Become a leader in the party and organize other people to become leaders, to make the party more progressive, more liberal.

You mentioned in the film, I think, that sometimes you fear that you’ll go to sleep and wake up and our democracy will be gone.

Oh yeah. Oh yeah.

How do you think you’ll know when it’s gone? It seems like there are so many signs day by day that it’s going or it’s close to gone. And for a lot of people, in many ways, it is gone.

Well, we must not allow that to happen, but you have someone in the White House like we have today, taking the position that he’s taken, and taking us back to another time, to another place. We’ve come too far, we’ve made too much progress, to slow down or to go back. So we must go forward.

I know that you’re going through some difficult times in regard to your health. I’d be interested to know how you’re feeling.

Well, my health is improving. I’m feeling good. I’m doing better. And I’m going to continue to listen to the doctor and try to eat right and get enough rest and sleep. But I have good days and days not so good. But I feel good today.

I’m very glad to hear that. I wonder what you think you can realistically hope to see change in your lifetime around issues of racism and racial inequality?

Well, I hope the day will come when we will see more people of color, more women, elected to higher and more responsible positions. And I think it will happen. To have women, to have Hispanic, Asian-American, and especially African-Americans, in places of high responsibility is going to help educate, sensitize, and make a better country and a stronger country.

Do you think activists today should approach these issues more with your attitude, or are some people needed who are less patient and who approach these issues much more confrontationally?

Well, I think we need the energy, the commitment and dedication, of all people, but especially young people. And people of a certain age, they’re much more willing to push and pull and not give up or throw in the towel. But there’s roles for people to play, and we should never ever give up on the different roles that we can play. Some individuals can play one role much better than others.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity from two conversations on June 2 and June 4. Good Trouble, executive-produced by CNN Films, will be released in theaters and on demand by Magnolia Pictures and Participant on July 3.

*This article appears in the June 8, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!