This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Leon Broussard IV was 4 years old when he made his first superhero costume. By 13, he had created a Spider-Man outfit with fully functional web-shooters capable of flinging a homemade sticky solution some 20 feet, building the slingers by himself out of a disassembled Bic lighter. By 15, the honor-roll student and aspiring engineer had taught himself how to use a 3-D printer to build parts and was selling incredibly detailed props to friends and family as a business.

And about six months before his 16th birthday, without warning or outward signs of depression to his family, Leon took his own life. “Losing someone to suicide is a different type of grief,” said his mother, Jessica Padilla. “The pain that they struggled with gets transferred to everybody who they were connected to.”

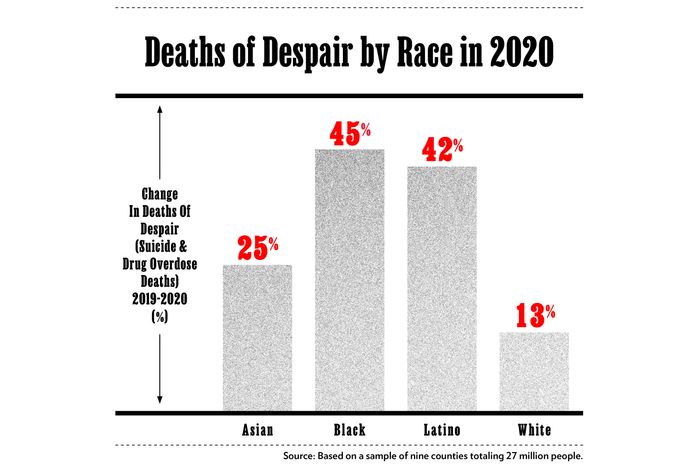

The loss suffered by Leon’s family was shared by an increasing number of people of color across the United States in 2020. New data from some of the largest metro areas shows a surge of “deaths of despair” — suicides and fatal drug overdoses — last year among people of color, leaving deep wounds in families and communities across the country already hit especially hard by the pandemic, economic downturn, and the prominent police killings of people of color such as George Floyd. Though the data is a sample of the nation and preliminary, experts warn the country can’t wait to address severe structural inequalities in mental-health care and a lack of data about what drives suicidal and drug-use behavior among youth of color.

The groundbreaking research on deaths of despair by Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton found that they rose markedly among middle-aged white people from 1999–2013 across the nation, in both rural and urban areas. But while Case and Deaton focused primarily on middle-aged whites in their 2015 research, more recent work suggests that the same forces of rising suicide rates and the opioid epidemic have been affecting Black and Latino Americans as well, albeit more among youth than middle-aged individuals. “It makes me very sad to hear that you are finding suicide rates rising in Black and Hispanic communities,” Dr. Case wrote in an email, but cautioned against coming to conclusions without national data.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will not release a national breakdown of suicide deaths by race for at least another year. But several of the largest U.S. counties provide public data about the circumstances surrounding each death investigated by the medical examiners’ offices. Intelligencer analyzed data from nine of these counties, which together contain more than 27 million Americans, or about one in every 13 people in the U.S.

These nine counties include the areas around Los Angeles, Chicago (Cook County), Houston (Harris County), San Diego, Milwaukee, and Fort Worth (Tarrant, Denton, Johnson, and Parker Counties). The nine counties were chosen for their large populations, availability of data, and diversity; all are heavily urbanized and most include a higher percentage of people of color than the national average. (Suicide rates in rural areas are often higher, but since rural counties are usually small, it is not feasible to build a significant sample of people from rural communities to analyze.)

The aggregate suicide rate in these counties increased among people of color from 2019 to 2020: up around 17 percent among Black people (to 6.3 deaths per 100,000 people), 14 percent among Latinos (3.5), and 9 percent among individuals of Asian descent (6.7). (Although even with these increases, no racial group had a suicide rate even half as high as that among white Americans, which was 14 deaths per 100,000.) Recent studies examining statewide data have found similar patterns, such as the Black suicide rate doubling in Maryland in the first half of 2020. “There’s nothing to suggest to me that these numbers shouldn’t hold up nationally,” said Dr. Sean Joe, a professor and suicidologist at Washington University at St. Louis. Over the same period in these counties, suicides among white Americans declined 15 percent, although this may not be reflective of a larger national pattern given that suicide rates had been steadily rising among white people for decades and the sampled counties included almost no rural areas.

Though the exact increase in suicides among people of color across the U.S. last year won’t be known until the CDC releases its complete data, survey data it already collected asking adults about their mental health during the pandemic showed increases in thoughts of suicide and substance use among Black and Latino people at rates that were roughly twice as high as among white respondents. (Nationally, suicide rates have historically been highest among Native Americans, but there were too few Native Americans in the counties with data to say anything definitive about their rates of death last year and the data available to the public is scant.)

The increases in deaths of despair and suicides in 2020 add to decades-long trends among young Black and Latino people. A 2019 article by Dr. Michael Lindsey of the McSilver Institute and his collaborators showed a 73 percent increase in attempted suicides by Black youth from 1991 to 2017. “We have been seeing these numbers increasing over the last 20 to 25 years or so but … this perfect storm of the pandemic and the racial reckoning is only going to accelerate the trend in an upward trajectory,” he said.

When there is no note left behind, the person’s intentions may be unclear, and the medical examiner may erroneously mark an accident as a suicide or vice versa. Ruth Medrano’s 17-year-old son Deyvi Coreas, who is Latino, shot himself in an incident the medical examiner ruled a suicide, but Ruth believes was an accident while he was trying to take a selfie with a gun. “The way Deyvi was, we don’t believe he did it intentionally,” Medrano said.

As for drug-overdose deaths, they far outpace deaths by suicide across all races — more than 70,000 died nationally in 2019. Drug- and alcohol-induced overdoses jumped upward by 50 percent in the counties for which data was available. People of color made up 51 percent of overdose deaths in 2020, up from 48 percent in 2019. Overdose rates were highest in this sample among Black Americans (35 deaths per 100,000), followed by white people (21), Latinos (7), and Asians (3). These overdose deaths may not have arisen from a deliberate choice by the person to end their own life, but in some cases may be associated with the same toxic mixture of depression, alienation, and stress that contributes to suicide. “There is a strong correlation between heavy substance use … and suicidal behaviors,” said Lindsey. “But we don’t have enough longitudinal studies among Black youth to know whether it’s the substances that are driving one to engage in suicidal behavior or whether it’s the suicidal behavior that’s driving one to engage in illicit substances.”

As with suicides, national overdose-death data by race from 2020 will not be released by the CDC for some time, although it did release a bulletin announcing a large increase in deaths in preliminary data. Combined, drug-overdose deaths and suicides increased by 45 percent among Black people in the sample, 42 percent among Latinos, 25 percent among Asians, and 13 percent among white people.

Although recent media attention and scientific scrutiny have focused on opioid use among rural white Americans, opioid-overdose deaths have been increasing much more rapidly in the last five years among Black and Latino Americans. Fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid sometimes mixed in other drugs, accounted for about 80 percent of the increase in overdose deaths in these counties, according to medical examiners’ reports. Other kinds of overdose deaths — from cocaine, alcohol, methamphetamines, or other drugs, which are often grouped together under the umbrella term “deaths of despair” — also steeply increased among people of color in 2020 in the counties examined.

“I really don’t like the term [deaths of despair], because I think that consciously or unconsciously, it takes the attention away from the fact that people are really dying given structural racism,” said Dr. Ayana Jordan, an addiction psychiatrist and physician scientist at the Yale University School of Medicine. People in Native American, Black, and Latino communities died at a much greater rate due to COVID-19 than other racial groups because of poverty, lack of health care, and jobs that exposed them to higher risk. The resulting economic downturn hit Black and Latino populations especially hard as well, and school closures robbed youth of peer groups and psychological help. “There is a lot of loss, in loved ones affected by COVID-19 and disconnection from schools,” Lindsey said. “Schools are the largest provider of mental-health services to kids in the United States, and without that proximity to a behavioral-health support in school, how are you … getting your emotional and psychological needs met?”

In addition to the pandemic, several high-profile incidents of police violence may have played a role in increasing depression and suicide rates among people of color. Emerging evidence suggests that witnessing incidents like the killing of George Floyd takes a psychological toll on Black and brown youth. A 2018 paper in The Lancet showed that police killings of unarmed Black men were associated with reduced mental health among youths of color in the weeks following the deaths. Experiences of discrimination, even when they happen to another person, are connected to increased thoughts about suicide and long-lasting harm. “I think that engenders a sense of hopelessness or the perception that … it might happen to me, or it might happen to a loved one,” Lindsey said.

Dr. Caroline Silva, a professor in the psychiatry department of the University of Rochester, said one possible reason for a decline in white suicide rates in these nine counties may have been that COVID-19 was causing deaths among older white people who are otherwise most likely to take their own lives. “COVID is resulting in a lot of deaths among older adults, and older adults in the white population are also the ones who are at highest risk for death by suicide. And it’s likely that many who would be dying by suicide have instead died by COVID.” For people of color, suicide rates are highest in youth and decline afterward, so the people most at risk of death from the coronavirus were less often the same ones taking their own lives among Black and Latino Americans.

Although these explanations may shed light on national trends, the decision to engage in suicidal behavior or dangerous drug use is complex and individual people have widely varying motivations. Leon died by suicide months before pandemic-related lockdowns started last spring or the video of Floyd’s killing emerged in May 2020.

Though Leon did not leave a note, his mother believed the pain and stress of hiding his depression may have been too much for him to bear. The stigma surrounding mental illness may have prevented him from voicing his feelings, even to his close family. Due to a historical lack of investigation, more research is required to learn about what factors drive and prevent suicide among Black and Latino populations. “We need to invest more research dollars into investigating the risk factors and to really appreciate that the risk factors may look different across different racial and ethnic groups,” Lindsey said.

Beyond research, public-health experts suggested that investments in counseling and psychiatric help would be key to reducing the suicide rate and defusing the built-up stress of the pandemic. “We have to have more capacity: more psychologists, more social workers, more psychiatrists,” said Joe of Washington University. There is significantly less access to mental-health resources among many communities of color and a stigma against seeking counseling prevents people who need help from getting it. Even when a patient of color seeks out psychological help, a 2016 study showed that therapists were 30–60 percent less likely to return a Black patient’s calls than if a patient with a white-sounding name requested an appointment instead.

If similar patterns hold through 2021, drug-overdose deaths and suicides among people of color could continue their rapid increase. In fact, some experts believe that the cumulative trauma from 2020 could cause suicide rates to increase even further this year, though it’s not clear whether it would increase for white people as well as people of color. “Once we get past this immediate health threat of the pandemic, all the complicated grief and stress that people are experiencing will begin to have much more impact on how they feel,” Joe explained. “I would expect to see suicide increase after the pandemic.”

Lack of timely data from all 50 states harms the ability of public-health officials to build strategies to arrest increases in the suicide and overdose rates, leaving them responding to statistics that are years out-of-date. “The government has to invest in national systems that collect this data,” said Joe. “I think it would make a significant difference in our ability to respond faster, to monitor trends, and to think about who needs help the most and what might be most effective.”

For the relatives of those who took their own lives, the lack of data, prevention, and attention can be maddening. “Prior to 2020, the second-leading cause of death [among adolescents] was suicide … And that’s not spoken about enough,” said Jessica, Leon’s mother. “If the second-leading cause of death among teenagers was heart disease, we’d hear more about it, there’d be more being done about it,” Leon’s father added.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 for free, anonymous support and resources.