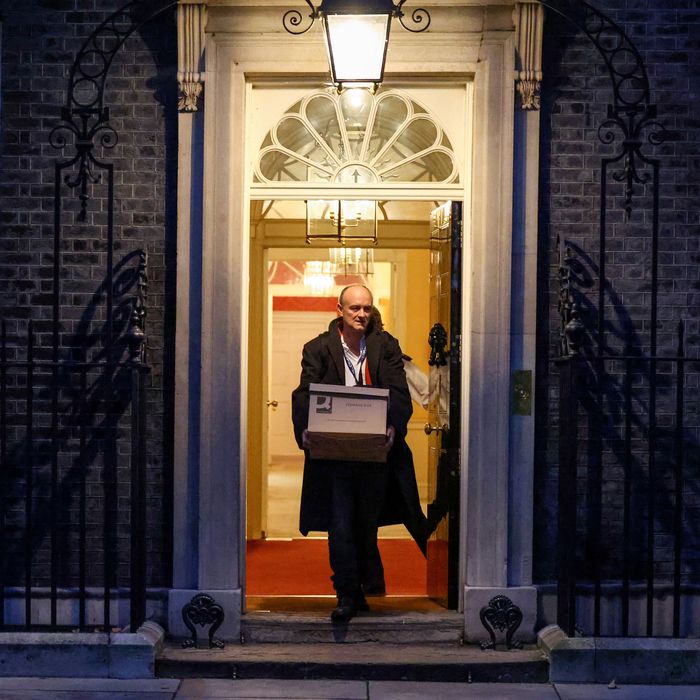

There is a joke in British political circles that Dominic Cummings exists to destroy prime ministers. After his organization Vote Leave won the Brexit referendum in 2016, David Cameron resigned. Cameron’s successor, Theresa May, stepped down when her Brexit deal was derailed. Now it appears to be the turn of Boris Johnson, Cummings’s former boss. Cummings was his most senior adviser — his de facto chief of staff — and the architect of the Tories’ 2019 landslide victory in the general election. A year later he lost a power struggle with Johnson’s third wife, Carrie, and left 10 Downing Street, the seat of British power, with a cardboard box in his arms.

Now, Johnson is flailing. There has been a series of leaks about his staff breaking the lockdown rules they created during the early months of the pandemic while, in the country they governed, people died alone, without loved ones for company. (Cummings himself was accused of breaking lockdown rules by leaving London for the north of England in April 2020 for, he says, security reasons.) It often seems as if Johnson and his team did nothing but party. There was a party for Johnson’s birthday; a party where invitees were encouraged to “bring your own booze!”; a party the night before the queen buried Prince Philip, her husband of 73 years, at a socially distanced funeral.

As a result of Partygate, as it is known, Johnson’s polling is in free fall, his Conservative Party is in open revolt, and his premiership is hanging by a thread. He is the subject of two inquiries: one by a civil servant, and one by the police. He has been accused of lying to Parliament about the parties, a resigning offense, and it is believed that, even if he hangs on, his party will drop him before the general election in 2024. It is also believed that Cummings, who earlier this year used his Substack to break the story of one illicit gathering at Downing Street in May 2020, is the source of some of the most damning leaks that have appeared in the British press.

Removing Johnson from power, Cummings tells me over Zoom, is “an unpleasant but necessary job. It’s like sort of fixing the drains.” He speaks slowly in a northern English accent. Cummings is half-myth in British politics — he gives very few interviews — but the man who faces me is slender and wan. His testimony is incredible because it is unfiltered. There have been whistleblowers before, but not one like this.

The charismatic Johnson, he says, was needed to deliver Brexit and defeat the leftist Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn in the election of 2019. “But after that,” he asks, “what’s the point of him and Carrie just rattling around in there and fucking everything up for everyone and not doing the job properly?”

Cummings is not from the usual class of Conservative power brokers. He grew up middle class in Durham. His father worked on oil rigs, and then became a farmer. Cummings studied ancient and modern history (Pericles and Bismarck) at Oxford. Upon graduating in 1994, he could have gone into banking or politics, but instead he moved to Russia because his history tutor, the maverick Norman Stone, told him, “Now’s the time to be in Moscow. It’s completely insane.” He co-founded an airline, was chased out by the Russian mafia, did not work for the security services (people do ask), and returned to England, where he worked on the ultimately successful campaign to keep the pound. It was his introduction to the political class, and his awakening.

“Everyone had all these ideas,” he says. “The public thinks this. The public thinks that. I went off and did all this research — polling and focus groups and stuff — and it turned out that what people thought in Westminster was kind of normal opinions was not actually true at all.” He was delighted by his discovery: “I rushed off, excited, to tell them. To say, ‘Look, I found all this out and it turns out that we’re all completely wrong. This is what people think.’ And instead of people being happy and updating their opinions they were very cross and just rejected it. And that was a very big shock to me.” He was 28. “That’s when I started to realize this terrible thing: A lot of senior people don’t really understand what they’re doing — at a quite fundamental level. I realized the whole business is full of people who don’t have a clue what they are doing and aren’t actually interested in learning, which is very weird to me.”

Cummings has never been a member of any political party. That his politics are opaque adds to his mystery and explains why he is so widely reviled in Westminster. Remainers hate him for taking them from Europe. Brexiteers hate him for not being a true believer in the cause. He attacks the Tory right and the Labour left. His tactics — invoking the possibility that Turkey would join the E.U. to bring racists to Vote Leave’s side, suspending Parliament to help force Brexit through — are considered immoral by his enemies. (The suspension of Parliament was also later judged illegal.) He seems attached to no creed. He is the best political operative in Britain, and since he left Downing Street he has been a chaos maker.

Privately, many people say they like Cummings. Benedict Cumberbatch, who played him in Brexit: Uncivil Wars, a dramatization of the referendum campaign, clearly did. He made him awkward and obsessive, both vulnerable and tough. “Why does no one like me?” Cumberbatch-as-Cummings asks his wife. But his bluntness makes enemies. Cummings has called David Davis, the former Brexit secretary, “thick as mince” and “lazy as a toad.” The media is fascinated by his attacks on Johnson in particular. Camera crews surround the north London house he shares with his wife, a journalist, and their young son, or follow him through the streets.

He believes that gifted people are repelled by politics. “When you talk to them, increasingly their attitude is: Politics is a shitshow, government’s a shitshow, we don’t want to get involved with that, you’re dealing with clowns, you don’t build anything.” Instead, “a lot of these people prefer to build their own kind of walled garden where they can feel like they’re building something that’s worthwhile and creating wealth and doing their own thing and thinking increasingly: How do I insulate myself from politics and government? All of which is a very bad thing.”

Politicians, meanwhile, are obsessed with the media and little else. “People just don’t understand the extent to which they are dominated by what’s going to appear on TV tonight what’s going to appear in the papers tomorrow,” he says. Johnson is an example of a man who governs — or performs — for the media. In Cummings’s telling, he is an imbecile. “In January 2020,” Cummings says, “I was sitting in No. 10 with Boris and the complete fuckwit is just babbling on about: ‘Will Big Ben bong for Brexit on the 31st of January?’ He goes on and on about this day after day. Eventually I say to him: ‘Who cares? What are you talking about? Why are you babbling on about Big Ben? It’s completely ludicrous. We won the election a few weeks ago. We have an eighty-seat majority. You are literally only in this study because for six months we actually had a plan that focused on the country, not on the stupid media. And that’s why we won, despite all the pundits saying we are idiots, we didn’t know what we are doing. Now we have proved them wrong, we have an eighty-seat majority, we don’t have to worry about their babbling.’” He looks aghast: “‘Why the fuck are we sitting around having these meetings about what will the Sun do tomorrow about Big Ben?’”

Cummings says he wanted to tackle the problems of the state: productivity, skills, schools, NHS management, national security, defense procurement. He once told a journalist, “I guess I’m plagued by worries of disaster more than is normal.” But he says that when he pressed this on Johnson, “He looked at me as if I was completely insane. And that was an instant tension. He sees his job as just to babble to the media every day. I saw the job as actually thinking about what’s important. And the truth is, almost all MPs agree with him and think I’m” — and his voice trails off and he sounds wondering — “stupid.”

What is Johnson interested in? Monuments, says Cummings. (Johnson’s childhood nickname for himself was World King.) Johnson thinks: “What would a Roman emperor do? So, the only thing he was really interested in — genuinely excited about — was, like, looking at maps. Where could he order the building of things?” Cummings says Johnson fantasizes about “monuments to him in an Augustine fashion. ‘I will provide the money. I will be a river to my people. I will provide the money that builds the train station in Birmingham.’ Or whatever. ‘And it will have statues to me, and people will remember me after I am dead like they did the Roman emperors.’”

This Johnson is incurably trivial, lazy, and self-absorbed. Ideally, Cummings says, Johnson would have understood the need to delegate actual governance to others. “And after the election he didn’t want to play that role. Our relationship got increasingly bad because he was saying to me, ‘Why you spending your time off doing all these things instead of with me?’ And I was saying, ‘Well, because you’re spending more time in stupid meetings talking about Big Ben bongs and I’ve got no interest in that.’ I was trying to have proper meetings about important stuff, trying to drive the government agenda on.”

Much has been made in the British press about Cummings’s battles with Carrie Johnson, a 33-year-old former director of communications for the Conservative Party, who began her affair with Johnson when he was still married to his previous wife. “Of course,” Cummings tells me, “Carrie’s in his ear, saying to him: ‘All the media is portraying you as a puppet, you’re the one who won the election, you should be the one who seems in charge. It’s all very damaging that you’re seen as a sort of buffoon who Cummings boots around.’ She wanted rid of me, and I also didn’t want to stay in that kind of dysfunctional environment. So, the whole thing just kind of snowballed.”

“It’s perfectly reasonable,” he adds, “for a prime minister’s girlfriend, wife, husband, boyfriend, whatever to have views about things. The problem was that she went into her own parallel briefing operation from the flat to the media, which is completely disastrous for government communications, particularly in a pandemic. She’s very forceful” — he laughs — “and he hasn’t got the balls to say to her, ‘Listen, I’m prime minister and this is what I’m doing.’ She thinks that she understands a whole bunch of things about politics and communications and whatnot.” He pauses: “She doesn’t.”

Is it fair though? What he’s doing to Johnson now? He looks at me as if I am a child. “What’s fairness got to do with anything? It’s politics. All this is not fair. The fact that someone wins an election doesn’t mean that they should just stay there for years, right? If you’ve got a duffer, if you think someone can’t do the job, or is unfit for the job. My basic approach to it was there was a world in which he accepted his limitations and accepted that No. 10 could work in a certain way with him there as prime minister. But if he’s not going to do that and if he’s just going treat the place like his own …”

He stops for a moment, then says, “You know, as he said to me, ‘I’m the fucking king around here and I’m going to do what I want.’” Cummings speaks slowly and deliberately: “That’s not okay. He’s not the king. He can’t do what he wants. Once you realize someone is operating like that then your duty is to get rid of them, not to just prop them up.”

What’s next? “Instead of shoving him out the door?” he asks. He won’t say. Perhaps he will build himself a walled garden. Then he says he will reread Anna Karenina. “I read all sorts of different crazy stuff,” he says, “and then I write about it on my blog. That suits me for the moment.”