This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In mid-September, I attended the National Conservatism Conference in Miami, where Republican politicians, right-wing thought leaders, and various party apparatchiks had gathered to articulate their vision of the conservative movement’s future. The National Conservatives are only one faction vying to define the Republican agenda, but in a short period of time, they have sharpened their focus and expanded their influence, and the conference gave them a forum to display the dominant position their ideas have achieved on the right. Kevin Roberts, the president of the Heritage Foundation and one of the conference’s speakers, recognized their triumph when he announced from the stage, “I come not to invite National Conservatives to join our conservative movement but to acknowledge the plain truth that Heritage is already part of yours.”

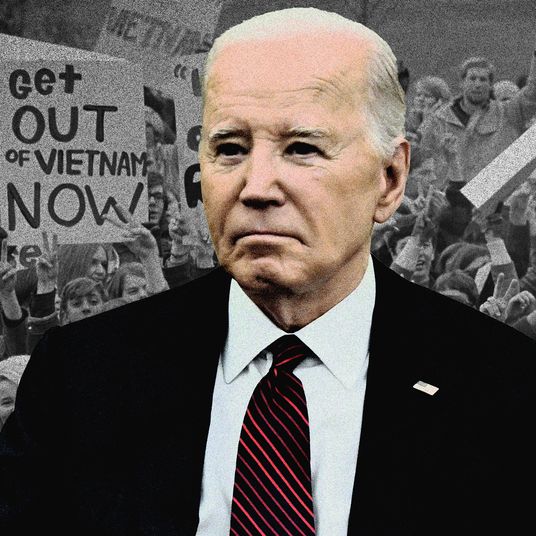

What exactly this movement entails has been the subject of a long-running debate largely obscured by the figure of Donald Trump. When Joe Biden warned in August of the rise of “semi-fascist” ideas on the right, even many Trump critics suggested that the president had gotten carried away. CNN’s John Avlon said this rhetoric was “not befitting” a president. Larry Hogan, among the most staunchly anti-Trump Republicans left in the GOP, scolded Biden for his “divisive rhetoric.” The implication was that it was a miscategorization of Trump and a smear of his followers to suggest that his anti-democratic behavior in any way resembled an ideology, let alone the fascist regimes of the 20th century. And it is true that Trump gravitates toward power instinctively; as president, he dispensed with democratic norms in large part because he did not understand them. Trump’s authoritarianism is sub-ideological.

But that does not mean his style of governance defies theorization or a philosophical rubric. The chaos of the Trump presidency has given way to a period of rethinking on the right, the result of which is a political and intellectual infrastructure determined to carry out his despotic impulses in a more systemized and, its supporters hope, victorious fashion. They may not call it fascism or semi-fascism, but this is only because the word has become a universally recognized slur since World War II. To most Americans, fascist simply means “bad,” and nobody self-identifies as “bad.” People imagine democracy and fascism as a simple binary, leaving them unable to acknowledge political systems that reside in the vast space between the two. But this middle ground between Reagan and Mussolini is where the Republican Party’s most influential ideologists and power brokers are consciously heading.

Semi-fascism contains many features of democracy, like contested elections and permissible criticism of the ruling party, but without the liberal guardrails that maintain democracy’s openness and stability, such as a judiciary, bureaucracy, and news media that are empowered and motivated to check abuses of power. Thus semi-fascism has a nasty tendency to slide into something more like the outright version, in which effective public opposition to the ruling party becomes impossible. Two decades ago, Vladimir Putin’s Russia looked very much like Viktor Orbán’s Hungary does today, and some observers still considered it a democracy, albeit one with challenges and limits. Today, Putin has seized so much power that even though voters have regular opportunities to defy him at the ballot box, it’s unlikely they ever will.

The Republican Party’s ascendant semi-fascist wing wishes to take several steps down this road. I watched the conference’s attendees practically declare they would do so. Their methods and goals are ones that if embraced by their opponents would unquestionably (and correctly) be described as authoritarian or worse. Nobody expressed any fear that a right-wing state dedicated to endless political warfare might violate anybody’s rights. The only rights they respected were those of red America. The only risk that concerned them was losing.

South Florida has attracted a huge collection of professional conservatives with national aspirations, some of whom were drawn away from New York and Washington, D.C., during the pandemic, and almost all of whom gravitate not toward the former president in Palm Beach but rather toward the state’s governor, Ron DeSantis, the near-unanimous-favorite 2024 presidential contender of both the movement and the party’s Establishment. The halls of the Miami Marriott were teeming with conservative networkers, and the panels were especially well stocked with a class of once-marginal right-wing pundits — Joshua Hammer, Sean Davis, Mollie Hemingway, Michael Anton, David Reaboi — who are far more in tune with the desires of the audience than the largely Trump-skeptical class of incumbent conservative columnists who still make appearances in the mainstream media.

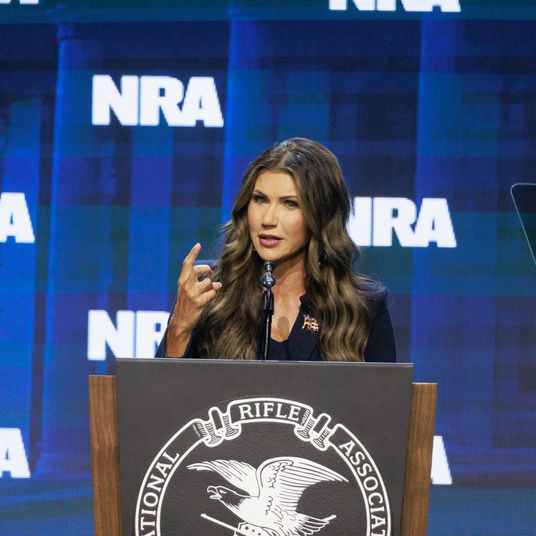

But the conference’s speakers were not confined to the kind of insurgent figures who provide color at freak-show events like CPAC or even previous iterations of the National Conservatism Conference. Quite the opposite; at times, the gathering had the flavor of a party convention. This year’s roster included the presidential candidate favored by the party’s Establishment in 2016, Marco Rubio, who conspicuously included himself in the movement’s ranks (“those of us who call ourselves National Conservatives”). It featured, in addition to DeSantis, the head of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, Rick Scott; Josh Hawley, the junior senator from Missouri; the financier Peter Thiel; and several candidates for Congress. They were joined by some of the leading lights of the conservative intelligentsia, people who command large social-media followings, head powerful think tanks, or have held influential positions in government: Rod Dreher, Christopher DeMuth, John Yoo, Yoram Hazony. The conference was organized by the Edmund Burke Foundation and co-sponsored by 14 other conservative organs, including the Heritage Foundation, the Claremont Institute, and the Hillsdale College Graduate School of Government.

And while every political conference has points of disagreement and speakers harping on their chosen hobbyhorse, this one was striking in its unified view of the world the participants face and the response they believe is necessary. Almost every speaker repeated a version of the following: The “woke” revolution has captured the commanding heights of American education, culture, and even large businesses, from which positions it is spreading and enforcing a noxious left-wing ideology. This poses an existential threat to conservatism, culturally and politically. Conservatives must therefore fight back by using state power to crush their enemies on the left — a notable break for a movement that, in the pre-Trump days, had at least pretended to stand against “big government.”

It was not so much that they had changed their policy goals or even their political strategy as that they had lost faith in the potential for normal politics to function. Every one of them demanded extraordinary measures — what Trump has called iron-fisted rule — as the only alternative to political extinction.

A few samples of the rhetoric from the stage give the overall flavor. Rachel Bovard, the senior director of policy at the Conservative Partnership Institute: “Wokism is not a fever that will pass but a cancer that must be eradicated. And the free market won’t do it.” She added that “in this new reality, the only institution with the power to contend with and conquer the Woke Industrial Complex is the government of the United States.” Conservative lawyer and former Human Events publisher Will Chamberlain: “We’re not in a peaceful environment with the Democratic Party,” and the key objective must now be “the willingness to use government power to achieve conservative ends.” Senator Scott: “The militant left wing in this country have become the enemy within.” Hillsdale professor David Azerrad: “Imagine if we had a core of Republicans who were committed to defund and humiliate the institutional-power sectors of the left.”

Two models for the emerging right-wing state came up repeatedly. The first was the DeSantis governorship. Attendees were entranced by his war on the left and particularly admired his retaliation against Disney for having criticized his restrictions on LGBTQ+ discussions in schools (which critics call the “Don’t Say Gay” law). DeSantis had had the guts to punish one of the state’s most powerful firms and, the conferees believed, shown how all of corporate America could be brought to heel.

The other model was Orbán’s Hungary. One attendee came away impressed with the “seemingly ubiquitous Hungarians.” (I now have a copy of the latest issue of Hungarian Conservative.) These Hungarians were greeted as liberators, and Orbán’s regime, which has taken control of the judiciary, the press, and the universities while using corruption to pressure major businesses to support the government, was the object of widespread envy. The European Union recently voted to withhold funds to Hungary, which it has deemed no longer democratic. Orbán’s American admirers see this response merely as confirmation that he is making the correct enemies.

DeSantis’s liberal critics have sometimes compared his methods to Orbán’s, but at the conference, this comparison was invoked as praise. A DeSantis spokesperson pointed to Orbán’s regime as an inspiration; an Orbán spokesperson pointed to DeSantis’s government as affirmation of the Hungarian leader’s actions. That Orbán and DeSantis are both colorless functionaries ought to drive home the fact that this movement is not, as its critics often jeer, a personality cult. Many of the conference members retain an affection for Trump, but they are not hung up on him personally so much as they are mobilized to wage war on his enemies. The appeal of semi-fascism in Hungary, and its incipient version in Florida, lies not in the men but in the systems they have built, which can be replicated.

One apparent paradox of this movement is that, even as it labels its political rivals as domestic enemies and dreams of using the power of the state to humiliate and destroy them, it does not view itself as authoritarian. Seen from the inside, fascist movements historically feel encircled and vulnerable, and the same holds true for today’s semi-fascist right. What’s more, their sense of weakness is not always a matter of pure imagination. It is true that social values around race and gender have moved leftward since Barack Obama’s second term. It’s true that the mainstream media treats claims by Republicans more skeptically than it has in the past. And it is also true that popular culture and corporate America have reviled Donald Trump.

But from these isolated strands of reality, the National Conservatives have spun a fantastical narrative of victimization. One blind spot in their analysis is that they have dismissed the possibility that liberal society has any capacity to moderate. In the real world, Democrats nominated their most moderate candidate in 2020, the party is now actively funding the police, and the New York Times’ op-ed page publishes regular columns denouncing cancel culture, developments that the National Conservatives’ rhetoric presumed impossible. Instead, they have looked at the angry atmosphere of the post–George Floyd protests as the starting point of a social revolution that, they fear, will only accelerate.

The National Conservatives have also ignored the causal role Trump’s grossly racist and sexist behavior played in inciting this backlash. One moment was especially telling: At a panel devoted to race, I asked if any panelists would agree that Trump had ever made racist statements in public, which even his Republican allies have acknowledged. None of the panelists conceded this. Indeed, the panelists’ entire narrative of the Trump era was one of persecution. So while his critics see Trump’s insurrection attempt as the defining event of the era, his supporters see this as at worst a minor lapse. By their way of thinking, the true insurrection was undertaken against him.

And while their narrative of oppression may be deeply delusional, their strategy follows from those assumptions in a completely rational way. They have identified the elements of the conspiracy that, they believe, destroyed Trump: woke corporations, election fraud, the deep state, and the media. And they have devised plans to neutralize them all.

The National Conservatives often speak disdainfully of corporations and libertarianism, which has fed into a belief that they have broken with the party on its traditional agenda of low taxes for the wealthy, deregulation, and opposing social-transfer payments. Ross Douthat posited hopefully in the New York Times that the National Conservatives might finally force the Republicans to abandon their opposition to taxing the rich.

But this misunderstands what the National Conservatives find objectionable about corporations and markets. The National Conservatives’ statement of principles is vague on economics, denouncing socialism while attacking “transnational corporations” for “showing little loyalty to any nation,” damaging “public life by censoring political speech, flooding the country with dangerous and addictive substances and pornography, and promoting obsessive, destructive personal habits.” This is a moral critique, confined to a trivial percentage of businesses — very few of which, after all, are engaged in content moderation or the sale of drugs or pornography — and implies very little change to the traditional Republican pro-business stance.

National Conservatives consider corporations to be “woke” enemies, or at least potential enemies, and see the power of the state as a lever to compel them to endorse conservative positions or at least refrain from endorsing liberal ones. They propose to pressure tech companies like Twitter and Google to drop content-moderation policies like bans on disinformation or hate speech. They wish to pressure corporations to not take positions in defense of voting rights or against forms of social discrimination. And they view investment funds using environmental, social-welfare, and good-governance criteria as a mortal threat. On all these issues, the National Conservative position is essentially identical to The Wall Street Journal’s editorial line.

The National Conservatives have not worked out anything close to a “populist” alternative to traditional Republican economics. The conference’s participants included Republicans who have placed themselves to the party’s right on size-of-government issues. Scott has angered his colleagues by proposing to raise taxes on the non-rich and subject every legislated government program to an automatic phaseout. Blake Masters, the Republican candidate for Senate in Arizona, mused that Social Security ought to be privatized before his horrified advisers apparently shut him up on the subject.

At a private reception at the National Conservatism Conference, Masters endorsed the use of state power to achieve conservative ends. “Libertarianism doesn’t work. Totalitarian leftism doesn’t work either,” he argued. (“Sounds like he is absorbing the Viktor Orbán lesson,” concluded conservative journalist Rod Dreher, who is Orbán’s most ardent intellectual defender Stateside.)

The embrace of National Conservatism by the likes of Thiel, Scott, and Masters shows that authoritarianism and libertarianism do not lie in irresolvable tension. Indeed, the two strands of thought have long blended together easily.

There is a tradition of conservatism that distrusts democracy precisely because it gives the people too much power to redistribute wealth. In his classic 1953 book, The Conservative Mind, Russell Kirk warned that democracy meant legalized plunder of the wealthy: “Taxation without representation certainly is tyranny, yet precisely this is introduced by democrats who give power to the unpropertied classes: men of property, the rampart of a state, are abandoned to be plundered at discretion of the ochlocracy.” Ochlocracy means “mob rule” — a fear that has haunted the American right and that it has never really surrendered.

During the Obama era, Thiel — a featured speaker at the conference — despaired, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” A decade ago, DeSantis dedicated an entire book to the theme that policies that tax the rich to benefit the rest of society pose a fundamental threat to liberty. This economic-based distrust of democracy is an important source of support for authoritarianism on the right.

Throughout the Trump era, acquiescence has been the order of the day for the vast majority of the Republican Party, which went along with Trump’s repeated attacks on democratic norms — either quietly, like Paul Ryan, or loudly, like Newt Gingrich. This is a familiar pattern in disintegrating democracies. Would-be dictators gain crucial support from allies in the political system who may not be committed authoritarians themselves but side with a factional leader who will advance their policy goals at the expense of democracy. The public tends to fixate on the personality of the charismatic authoritarian, but it is the choices of their coalition partners that mostly determine whether they succeed or fail. Political scientist Juan Linz calls these allies “semi-loyal actors,” and sociologist Ivan Ermakoff describes these alliances of convenience as “ideological collusion.”

With a handful of exceptions, most of them since exiled from the party, Republicans have mostly chosen ideological collusion as their response to Trump’s violations of democratic norms. It was only when he summoned a mob to ransack the Capitol that his party recoiled in disgust. And even here, their revolt lasted mere days before they reasoned their way back to ignoring him. Trump was a spent force, they told themselves, so there was no point in alienating him or his supporters by impeaching him for his crimes.

Since that crucial decision to go forward together, insurrectionists and all, the thrust of the conservative project has been to build a movement that can blend the party’s traditional small-government conservatives with the Trump cultists, paramilitary organizations, and QAnon adherents. At the ground level, this work has involved the infiltration of the party ranks at every echelon, from poll-watching volunteers to candidates for statewide office, some of whom continue to tout Trump as the true winner of the 2020 election. At the more abstract level, the project is the construction of both a theoretical and a practical framework for the party’s authoritarian-libertarian synthesis.

Major corporations played an important role in civil society’s backlash against Trumpism — declaring boycotts of donations to election deniers, denouncing voting restrictions, and making statements in favor of rights for women and minorities. While liberals often rolled their eyes at these measures, conservatives took them as a deadly threat. Republicans are determined to regain the whip hand and ensure pushback like this never happens again.

The amalgamation of traditional Republicanism and Trumpian populism was on its clearest display in the conference’s breakout session “Securing the Integrity of American Elections.” The panel was composed of veteran operatives, including Hans von Spakovsky and J. Christian Adams, two apparatchiks who have long been considered the leading experts on voting restrictions within party circles.

The overarching theme of the panel was that Democrats routinely engage in widespread voter fraud and that Republicans have failed to gain power because they have shied away from the hard work of rooting out this allegedly endemic cheating. “You’re not gonna get anybody elected unless you’ve got an honest election system in which they’ve got the ability to get elected,” said Spakovsky. “There’s obviously going to be fraud; we know there will be fraud,” said Jessica Anderson, a former Trump budget staffer now working at Heritage.

Despite Biden’s victory, the spirit of the panel was far from glum. The right’s newfound anger over Biden’s imagined election theft had made its agenda, once a backwater in the constellation of conservative issue groups, a first-tier cause. The panelists were almost giddy in their newly elevated status, with some expressing confidence that Republican officials could no longer placate them with mere lip service and would have to commit fully to their anti-fraud agenda. The 2020 election was a setback, but Trump’s refusal to accept the outcome would be a galvanizing event.

The battle lines were clear. Ben Ginsberg, the former Republican elections lawyer who had broken with the party over Trump’s attacks on the election result, had revealed himself as a traitor. (Adams called him a “now-turncoat Republican election lawyer.”) But this was a sign the party’s commitment to election security was now in the hands of true believers who would do whatever it might take.

Better still, Trump’s campaign to discredit the election results had inspired thousands of self-appointed observers who are now being trained and mobilized into a more muscular apparatus to enact even more stringent voting restrictions and to police the polls in search of fraud. “We are growing fair-elections coalitions,” boasted Kerri Toloczko. “They are aggressive, fearless people.”

During a Q&A session, I raised my hand and asked the panelists if any of them believed Biden had legitimately won the election. Adams said the answer was “complicated” and declined to elaborate. Toloczko replied that whatever happened in 2020, they needed to learn lessons going forward to prevent a recurrence. None of the other panelists would say if Biden had stolen the election — suggesting that whatever they believed privately, they needed to act as if it were true, since it was such a potent source of energy for their cause.

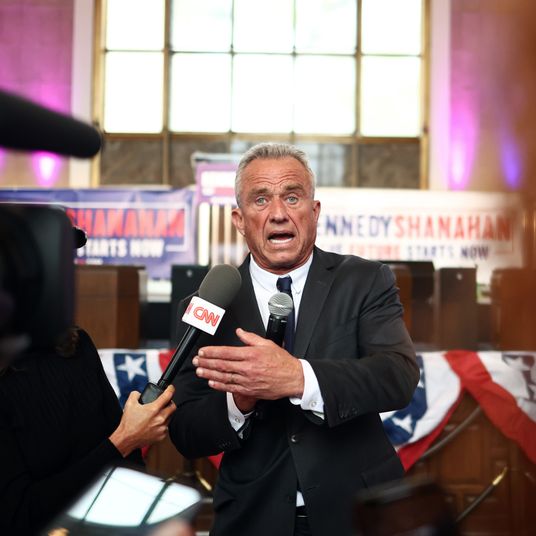

Another lesson the conference had taken from Trump is the importance of seeding loyalists throughout the administration and the federal government. Tom Klingenstein, the chairman of the Claremont Institute, told the crowd that Trump had called him the night before. Klingenstein recounted that, after a typically long Trumpian monologue, he asked the former president what he’d do if he had it to do over again. “He said, ‘People, people, people,’ ” reported Klingenstein. “He took advice from RINOs, as he said, for personnel decisions, which turned out to be bad. This time, he said, he knows the right people.”

The National Conservatives consider the military to be the most important target for political purification. Speaker after speaker lambasted the Pentagon as a hive of social liberalism. “We might be thankful that the generals at the Pentagon are such low-IQ incompetents,” sneered Darren Beattie, a former Trump speechwriter who was fired in 2018 for attending a conference with the founder of an anti-immigration site. “A powerful new ideology, commonly called wokeness, has conquered every institution in American life, including the military,” asserted Dreher. “The woke now control the Democratic Party, the entire federal government, the news media, academia, big tech, Hollywood, most corporate boardrooms, and now even some of our top military leaders,” claimed Scott. “We have to combat wokism in the military,” announced Klingenstein. “One standard I would judge a Republican nominee by: Is he committed to getting woke communism out of the military?”

This idea has gained surprising purchase on the right. The important context for understanding this obsession is the battle over Trump’s decision to clear protesters from Lafayette Square in 2020, after which Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, expressed regret. Mollie Hemingway of The Federalist devoted a lengthy section of her speech to relitigating this episode, which she apparently believes Trump handled entirely appropriately. The idea that famously conservative agencies like the military are infested with communist beliefs, or even progressive ones, is obviously fantastical. The rhetoric about purging woke communists is a pretext to purge anybody who is not a loyal rightist — a point driven home recently when Masters called for firing the entire military leadership and replacing them with “the most conservative colonels.”

Conservative anger at the media is a very old phenomenon, and Trump’s approach to the matter — declaring every unflattering piece of news about him to be ipso facto “fake” while relying on conservative media to transmit his message uncritically — served as a starting point from which the National Conservatives have plotted out a more cutthroat approach. Here, again, Orbán and DeSantis stood out as the models.

At one panel, The Federalist’s Sean Davis asked Balázs Orbán, an adviser (no relation) to Viktor Orbán, how his government is preventing the fake-news media from poisoning the minds of the youth. “Just as is done in Florida,” Orbán replied, explaining that the Hungarian regime used state power to prevent the left from indoctrinating the country in its ideology. (His spokesperson explained that he was referring specifically to “gender propaganda.”) He mocked the idea that the regime was behaving autocratically: “You can say I am autocratic, pro-Putin, pro-everything that is bad, but look, in Florida, in the United States, the Republicans are doing the same.”

The comparison sounded hyperbolic, even absurd, until the next day, when a DeSantis adviser detailed these methods and even embraced the same comparison. Christina Pushaw, whose official title is director of rapid response for the governor but whose role could be more accurately described as minister of propaganda, held forth at a panel on marginalizing independent media. The challenge, she explained ruefully, is that many older Americans, such as her parents, still give some credence to old-line outfits like the New York Times. This reputation, she believes, comes from the perception that they have access to both parties, so the correct response by Republicans is to freeze out the mainstream media. “If they have no access to any Republican elected officials, they are seen for what they are,” she proposed. Pushaw stressed that Republicans should not even concede that reporters are journalists at all. She instructed the audience to call them “activists.”

Pushaw told the audience that Orbán’s government gave her inspiration for this tactic. “The New Yorker wrote to Orbán and asked for comment on their hit piece, and they received a response that was just perfect. It said, ‘We are not going to participate in the validation process for liberal propaganda,’ ” she recounted, “and I don’t think we need to participate in that validation process either.” Instead, she noted, DeSantis gives access to conservative sites, which then get quotes and scooplets they can use to build their audience.

One might point out that the conservative reporters Pushaw wishes to promote as replacements for the mainstream media really are activists or at least make no effort to follow norms of objectivity. But this is not a rebuke to her strategy so much as it is an illustration of its purpose. She wishes to bring about an end stage in which terms like news and reporting sound impossibly naïve — it’s all either progressive activism or conservative activism. The effect of this rhetoric (and, one presumes, its purpose) is to erase journalist as an occupational category in the public mind.

Not surprisingly, the presence at this conference of a liberal journalist became a curiosity, then a threat. Some attendees greeted me politely. Others began photographing or filming me from a distance or from the side and circulating evidence of my attendance. By the second day, several panelists were calling me out from the stage.

Before the media panel, David Reaboi, a panelist, Claremont Institute fellow, and avid weightlifter, approached me and told me I was “the most full-of-shit writer.”

I smiled and thanked him. The hostility began to slowly escalate. Panelist and The Spectator editor Amber Athey, denouncing the perfidious media, warned, “Even here, goblinesque reporters lurk.” Reaboi tweeted a surreptitious photo of me hunched over a MacBook on my lap, tweeting, “Here’s the slumped-shouldered, ‘goblinesque’ @jonathanchait at #NatCon3. Was fun to tell him what I thought of him before the panel … He looks exactly like you’d expect him to look, doesn’t he?”

An image of their enemy was forming in their minds. My posture in the photo — I do tend to slouch, especially when typing — and failure to respond to his insult in kind represented a weakness they found contemptible. “That was awesome. Gotta love how the keyboard warriors suddenly get really quiet and lost for words the moment they are face to face with their targets,” chimed in Pushaw, before replying again, “He’s a ‘journalist’ in NYC who is creepily obsessed with our governor and came all the way to Florida to indulge his obsession.” (Reporting is again redefined as a form of inappropriate behavior.)

Reaboi proceeded to fire off a series of tweets calling me a “scumbag” and an “animal,” repeatedly referencing my “goblin-like” appearance. The next day, conservative pundit Jim Hanson tweeted a photo of himself at Disney World, posing next to a statue of a troll with a giant nose: “Found my boy @jonathanchait at #DisneyWorld.”

In some small way, I had come to fill the role of George Soros, whose face looms grotesquely from Orbán’s billboards in Hungary, or perhaps Emmanuel Goldstein from Orwell’s “Two Minutes Hate.” Their abuse had a mode (public humiliation) and an aesthetic (portraying their target as creepy, subhuman, dangerous yet disgustingly weak) that was slightly, one might even say semi-, fascistic.

As time passed, what stuck with me most about the cascade of taunts was its undercurrent of glee. It was as if, in that confined time and place, amid the drab conference halls of the Marriott, they had created a miniature version of the world they wished to inhabit. They believed it was the future of the country, even the whole of the currently democratic world. And it was possible to imagine they were right.